The first American president known to have seen a psychotherapist while in the White House was Richard Nixon. Most probably could’ve used one—the drive for power that leads as far as the presidency must be pathological to start with—but Nixon was the first. Which says something about how therapy had permeated the mainstream by his time. Not long before, the idea of a president seeing a psychiatrist was the jumping-off point for satire.

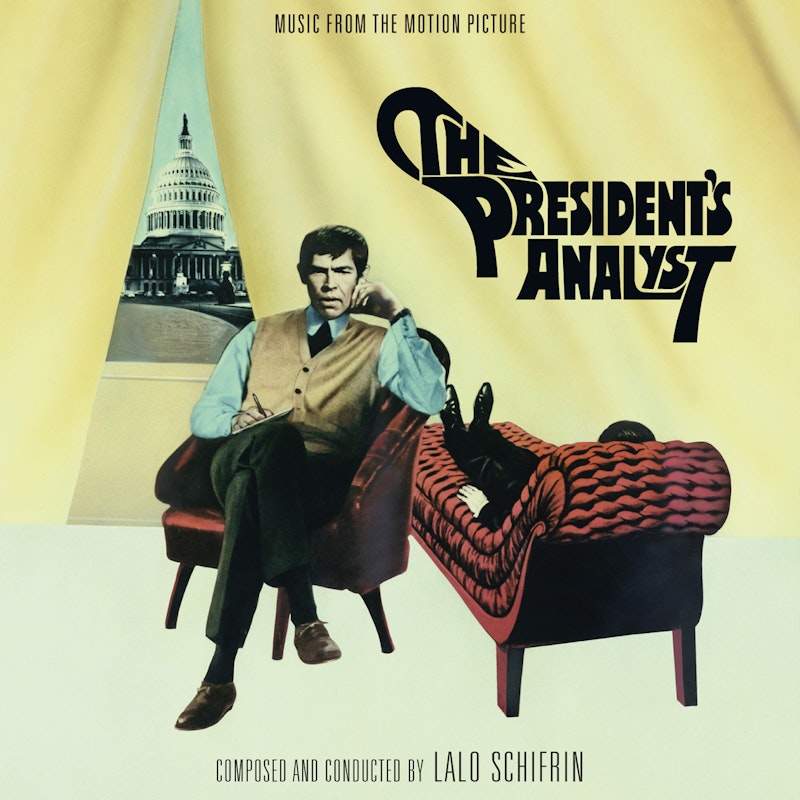

Specifically, The President’s Analyst came out in 1967. Written and directed by author and improv comedian Theodore J. Flicker, it follows psychiatrist Sidney Schaefer (James Coburn), who’s chosen to be the analyst for the (always unseen and unheard) president of the United States. Schaefer begins to crack under the pressure, flees his job, and soon becomes the focus for an international manhunt by the spy agencies of every nation on earth.

It’s not a great movie, but it’s entertaining, a nice oddity with some killer moments. Starting out straight-faced, it grows more surreal as it goes along, and ends with a ludicrous science-fictional conspiracy out of The Man From U.N.C.L.E. (which Flicker directed an episode of). The pacing and transitions are managed well, and despite the range of tones it holds together fairly well.

It’s not quite consistent enough to be even a cult classic, but it’s solid and unpredictable. The film opens with Schaefer’s patient Don Masters (Godfrey Cambridge), secretly an American intelligence operative, giving the doctor a monologue about a painful moment from growing up as a Black child; it’s an effective opening, and there’s some bravery in the way the film then completely abandons that tone in favor of crazier things.

Masters tells Schaefer he’s been picked to be the president’s psychotherapist, Schaefer moves to Washington, and the president soon comes to rely on Schaefer as the only man to whom he can confide the crushing burden of his office. The pressure, and 24-hour on-call schedule, takes a toll on Schaefer’s own mental health. He develops symptoms of paranoia, and soon slips away from official Washington, triggering an international manhunt as he stumbles through a country full of weirdness.

There’s a neatness to this: the growing absurdity of the film mirrors Schaefer’s growing disconnection from reality. It also shows the world as a mad place. So the plot reflects character at the same time as it builds a satirical vision. That’s a good structural approach for a satire to take.

And it works because not only the tone of the film but the character of Schaefer stretches to encompass the weirdness. Coburn doesn’t give a great performance, but he does a strong job of defining Schaefer and sticking to that definition as he moves among spies and suburban housewife karate masters and drug-trading free-loving rock stars. Schaefer’s both cracked and perceptive, a crazy point in a crazy world, just the right kind of a cartoon to join the film’s gallery of other cartoons: a liberal gun nut worried about right-wing extremists, Canadian Secret Service agents who resent being “the silent partner in North America,” the bloody rivalry between the uptight hard-asses of the Federal Bureau of Regulation and the young hippies of the Central Enquiries Agency. (A displeased FBI caused the studio to pressure the filmmakers into using replacement names for actual American intelligence agencies.)

Nerdy but insightful, Schaefer even gets to do some actual therapy onscreen. Captured by V.I. Kropotkin (Severn Darden), a Russian agent and gentlemanly rival to Don Masters, he convinces the Russian to let him go by listening to his problems and diagnosing his issues with his father. “All my life I’ve been miserably unhappy,” Kropotkin reflects, “but I always thought it was my Russian soul.”

The President’s Analyst isn’t really a film of ideas, but it deals effectively if briefly with the ideas it does touch on, and has a streak of grim if not amoral humor in its worldview. Schaefer wonders in an early discussion whether morality’s a social invention and murder justified by social needs; the rest of the film features a succession of international assassins killing each other to get the chance to abduct or kill him. Murder, in other words, is just the way the world works. In which case you could perhaps see the psychiatrist as a kind of sacrificial lamb, taking on the sin of the President’s complicity in the violence of the world.

It leads to a very 1960s fantasy-conspiracy: a corporation spying on the common man, and a scheme to embed technology into the brains of the population. It’s a paranoia that comes from a time of increasing automation, and it’s the negative image of what Schaefer does—instead of healing the mind humanistically, the conspiracy wants to dominate the mind technologically. It’s goofy, and the movie knows it’s goofy, but there’s enough of a thematic connection to Schaefer’s profession that somehow it holds together.

Nixon would be elected a year after the film came out; he’d been seeing Dr. Arnold A. Hutschnecker since 1951, and after Nixon’s election he spoke with him several times by phone and twice in the White House. In 1974 Hutschnecker argued, “The help a political leader might seek under stress to secure his emotional stability is not weakness but courage, and is as much in our national interest as it is in his.” It was clear then and it’s clear now that he had a point. The President’s Analyst brings this out with a nice cynicism: the world’s enough to drive you mad, if you let it—especially when you’re in charge.