This is the seventh post in a series on political films. The sixth, on Advise & Consent, is here.

"You can vent your aggressive feelings by actually killing people!" Dr. Sidney Schaefer (James Coburn) enthuses early on in the 1967 goofball satire The President's Analyst. "It's a sensational solution to the hostility problem!" Schaefer is talking to Don Masters (Godfrey Cambridge), a CEA spy agent who’s just admitted to killing a man in the line of duty. For Schaefer, this is a revelation; neurotic internal problems, he suddenly realizes, can be cheerfully, completely resolved through external political action. The nation is the brain and the brain is the nation. So if you're feeling neurotic, shoot a spy.

Political films always face a challenge in trying to show how politics affects the public. In Advise & Consent lots of senators and presidents solemnly declare that the lives of many will be affected if this secretary of state is chosen rather than that one. But since the action of the film all occurs in the corridors of power, you don't get much convincing evidence that everyday Americans exist, much less that their lot will be much altered by a senatorial vote.

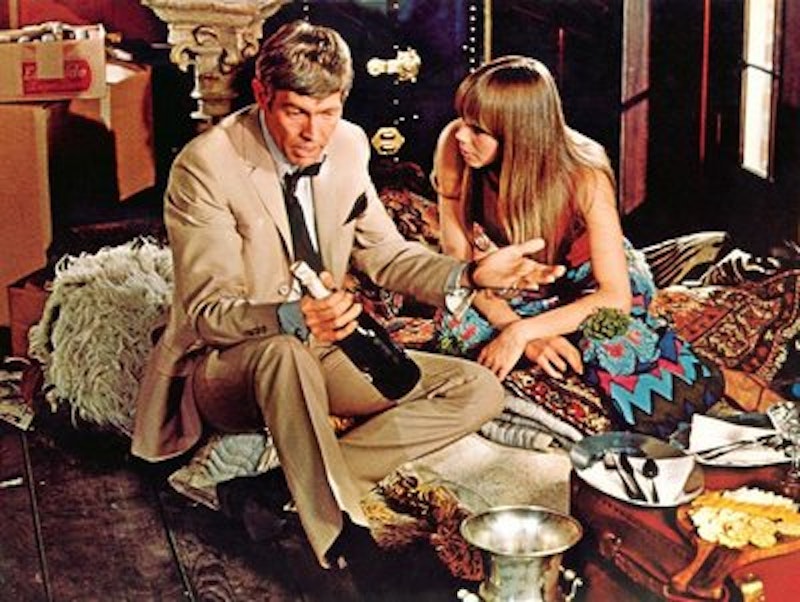

The President's Analyst, though, is a hippie-era film, and its looser, groovier structure makes it easy to break down the mental barriers between those doing the deciding and those getting decided. The president, who faces the heavy psychic burden of power, himself reaches out of his inner circle for relief by tapping Schaefer to serve as his analyst—the one man the leader of the free world can talk to about his worries and anxieties. Schaefer is at first thrilled at the opportunity, but he quickly learns that serving at the whim of the president has some serious downsides. Whenever he is wanted by the chief executive, flashing red lights go off in his home—or even, improbably, in his soup tureen when he's out at a restaurant—and he has to scurry to see the big guy. The sleeplessness compounds the stress of Knowing What No One Should Know; Schaefer worries he's followed by spies, and that his girlfriend, Nan (Joan Delaney) is out to get him. "If I was a psychiatrist, which I am," he expostulates, "I would say that I was turning into some sort of paranoid personality. Which I am!"

Many critics have pointed out that The President's Analyst is prescient in its warnings about surveillance. The US spy services really do watch incessantly. Nan really is a spy, and the bad guy of the film turns out to be The Phone Company (TPC), which (shades of the NSA) taps all phones all the time. Just because you’re paranoid doesn't mean that they're not after you.

The real off-kilter brilliance of the film, though, is in the way it presents politics not as a cynical game, or a patriotic duty, but as a kind of whacked-out psychic weight. Coburn's performance as Schaefer is gloriously unhinged; his toothy smile looks like his facial muscles are controlled from some remote locale. But he's hardly the only one in the film who politics sends round the bend. In a brilliant set-piece, Schaefer scurries away from his duties by hitching a ride with all-American New Jersey couple Wynn and Jeff Quantrill (William Daniels and Joan Darling). Wynn is an earnest liberal with a .357 Magnum in his car and an uneasy eagerness to murder in the name of tolerance. "The Bullocks next door? Real right-wingers," he tells Schaefer confidentially. "American flag up every day. Real fascists. Ought to be gassed. You know the type." When the family is set upon by spies trying to capture Schaefer, Jeff practically squeals "Muggers!" in glee, as she tries out her karate moves, and Wynn pulls his gun and blasts away. Exorcising hostility by killing people and self-righteously turning personal differences into an excuse for genocide. Isn't that what politics is all about?

The president is never shown onscreen; Schaefer meets him in a confidential sub-level, and their private conversations are never visualized or even paraphrased; we don't even hear Schaefer talking in his sleep, and when his girlfriend does, the prudish and censorious FBR move her to a hotel.

Like God, however, the president's physical absence gives him a spiritual omnipresence. No one knows exactly what the president has told Schaefer, but everyone—from the Canadian agents disguised as a Beatles-esque band to charming Russian spy V.I. Kydor Kropotkin (Severn Darden)—believe that the presidential revelations will give them the leverage they need to seize geopolitical power. The presidential neuroses become worldwide neuroses; the president's paranoid fantasies, whatever they may be, are everyone else's paranoid fantasy.

Only a band of free-love hippies with whom Schaefer hooks up (in various senses) seem immune—though their separation from real politik is a delusion in its own way. The film's most entertaining tour de force is a scene in which Schaefer makes love to one of the hippie bands in the tall grass, while around them a phalanx of spies from competing nations off each other to the strummed accompaniment of peace platitudes voiced by Barry McGuire (best known for "Eve of Destruction.") Even when you're wearing a bad wig and sunglasses while innocently having sex, you can't escape the president's brain.

The evil plan of The Phone Company is to turn brains into a public utility; they want to insert tiny tranceptors into everyone's cerebrum. They capture Schaefer in hopes of getting blackmail fodder to force the president to back their plan to give all Americans an individual number to replace their name. The brain plot is all explained through a cute advertising video add that mimics WW II propaganda films. The evil phone company, with its animatronic spokespeople, isn't so different than the government, reaching into your brain from afar, and directing your patriotic hostility.

Director Theodore J. Flicker uses a subtly disjointed editing style throughout The President's Analyst. Cuts within a scene, between one character talking and another responding, are often abrupt and placed just slightly off where you'd expect. As a result, Schaefer's life feels like it has spaces in it, or his plot is manipulated and disrupted by some outside force. He's himself, but something outside him is in that self, spying. Similarly, Kropotkin doesn't realize how profoundly his father's murder of his mother in the Stalinist purges affected him until Schaefer, flourishing a phallic banana, elucidates the Oedipal politics for him. Ideology and partisanship shape people's beliefs, actions, and selves in ways that are pervasive but difficult to see. Every brain is the president’s brain; we're all just a thing in his dream.