I just figured out why I like reading critics. It hit me while I was going over what a favorite critic had to say about another favorite critic. James Wolcott was a protégé of Pauline Kael's back in the 1970s, when New York City was a steaming heap of decay where very interesting movies got shown. Wolcott was a boy reporter with the lonely job of writing prose for the Village Voice that people would actually want to read. Kael, much older, was a film critic for The New Yorker and probably the best-known writer about movies in the country. She read his stuff and called him up one day, and from then on they hung out.

Decades later, Wolcott wrote up his memories of her in a piece entitled “Like Civilized People...” It's the best chapter in his very good memoir Lucking Out. We get to see an evening with Pauline Kael, and see that she is high-spirited, outspoken, friendly, down-to-earth and never full of herself. On the way to a screening, the cabbie says “nigger” and Kael tells him “Now, now.” The cabbie adds some remarks on the subject of blacks, good ones versus bad ones, and Kael says, “You may need to give the matter a little more thought.” At the end of the ride she leaves a good tip. Why? “I didn't want him to think I was using his racist talk as an excuse to undertip him,” she says. This strikes me as humane and respectful in a cruddy situation.

Later, at evening's end, Wolcott looks about him. It's the lobby of the Algonquin, and Kael has her circle of young critics gathered near. We've heard about “R.” from Newsweek, whose jeans “seem to sag in the back no matter how tight his belt is notched,” and there's a guy who sticks in Wolcott's mind for affecting “a facial arrangement of academic thoughtfulness.” Another fellow is described at a film screening: “I can tell from his forlorn, gallant wave to Pauline before he sits down that he's miffed he didn't arrive early enough to sit in the back row, forced instead to make do with a middle row far from the nerve center of activity.” Kael's in the back and Wolcott's at her elbow, taking note of the poor guy's exile. Taken person by person, his fellow acolytes don't seem to ring Wolcott's bell.

Even so. Everybody's talking, movie topics bob in the air, and Kael lobs an opinion or a bit of lore in each topic's direction: “Stella Stevens was so scrumptious in that film, you think she'd have had more of a career.” Then somebody else throws out what he thinks and the talk moves on. Vibes are good. No doubt the fellow with the flat ass still has his jeans drooping. The fellow who's po-faced may have his lips pursed with provoking judiciousness. Because Wolcott is an honest man, we know that the young narrator is “wearing jeans that probably need washing and nursing a Coke.” Not only that but the hotel made him put on a jacket and he's making discoveries. “You wouldn't believe how much lint there is in these pockets,” he says.

It's okay. A gathering of shabby nerds is having a good time and doing so by the underemployed means of talking to each other in a good-natured way. This happens because Pauline Kael has gathered them together and is leading the talk. Wolcott remembers that “she listens, she laughs, she passes along nuggets,” and that “she doesn't hold forth, she doesn't make pronouncements, and she doesn't traffic in absolutes, like Ayn Rand holding an indoctrination séance. 'Let's order a last round, like civilized people,' she says, and rings a bell.” The chapter has a passage about criticism and why critics do us a favor when they line up their thoughts and let fly. Wolcott might say—I think—that they cap whatever cultural phenomenon they address and thereby supply civilization with some of its high points. But Kael's use of “civilized people” is less ambitious and more comfortable. Wolcott may feel that way too, since he made her remark the chapter's title.

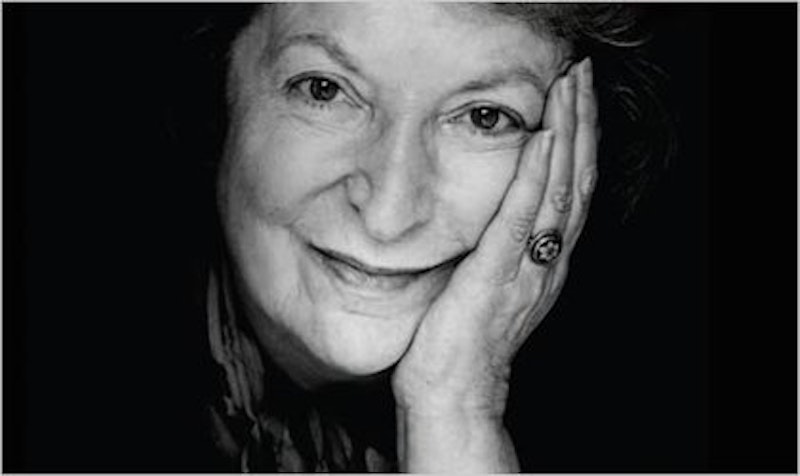

Pauline Kael (she died in 2001) has been my favorite critic for 35 years. When I read her there's a voice talking in my ear, like we're pals sitting close, and I'm happy to have it there. She confides her stream of personality readings and bent-lightning visual impressions and savvy insider bits. She's always honest and usually on the ball, and when I don't understand her I feel like she's reaching for something, not bluffing. She finds people to be absurd but she's happy to be around them, an attitude that works against bluff.

Now I find out that Pauline Kael in person was just how she struck me in print. I'm happy all over again, and I've discovered something. Thinking it over, I know very little about the debates Kael took part in, such as auteurism versus whatever she represented. Frequently enough I don't agree with her about one movie or another. She says the sled in Citizen Cane is gimmicky, I think a Hollywood movie found a way to lay open a man's soul. Given that I know little about film criticism, you'd think my favorite film critic (if I had to have one) would be someone who agreed with me film by film. Apparently not. I like Pauline Kael because I like her. I read critics for their company, and not much matters to me beyond that. Reading Wolcott's picture of Pauline and the boys huddling together, it really seems like enough.