1999 has long been acknowledged as one of the greatest years in film history, second only to 1939. The list of superlative American films from that year is staggering: The Blair Witch Project, American Pie, Election, Cruel Intentions, The Sixth Sense, The Matrix, Boys Don’t Cry, Varsity Blues, Fight Club, Office Space, Dick, Big Daddy, Drop Dead Gorgeous, Star Wars: Episode I—The Phantom Menace, Bowfinger, Austin Powers: The Spy Who Shagged Me, American Movie, The Best Man, Being John Malkovich, South Park: Bigger, Longer, & Uncut, Toy Story 2, The Iron Giant, Galaxy Quest, Three Kings, 10 Things I Hate About You, She’s All That, The Insider, The Virgin Suicides, Magnolia.

And American Beauty.

But even Alan Ball and Sam Mendes’ treacly and overwrought suburban melodrama looks a lot better today next to something like Revolutionary Road, Paul Dano’s Wildlife, or the pair of “struggling teen son” movies that came out in 2018 (one was gay, one was on meth). And if not better, more interesting; ditto for Paul Thomas Anderson’s Magnolia, my favorite movie at 11 years old but one I found unbelievably irritating at 26. I’ll try again when it plays at the Charles or the Senator, but I’ve always defended that movie’s most bizarre sequences, and like most of Anderson’s films its craft is undeniable. No one is swinging like him now except Ari Aster, whose Beau is Afraid couldn’t be dismissed out of hand unlike Damien Chazelle’s abominable Boogie Nights rip-off Babylon.

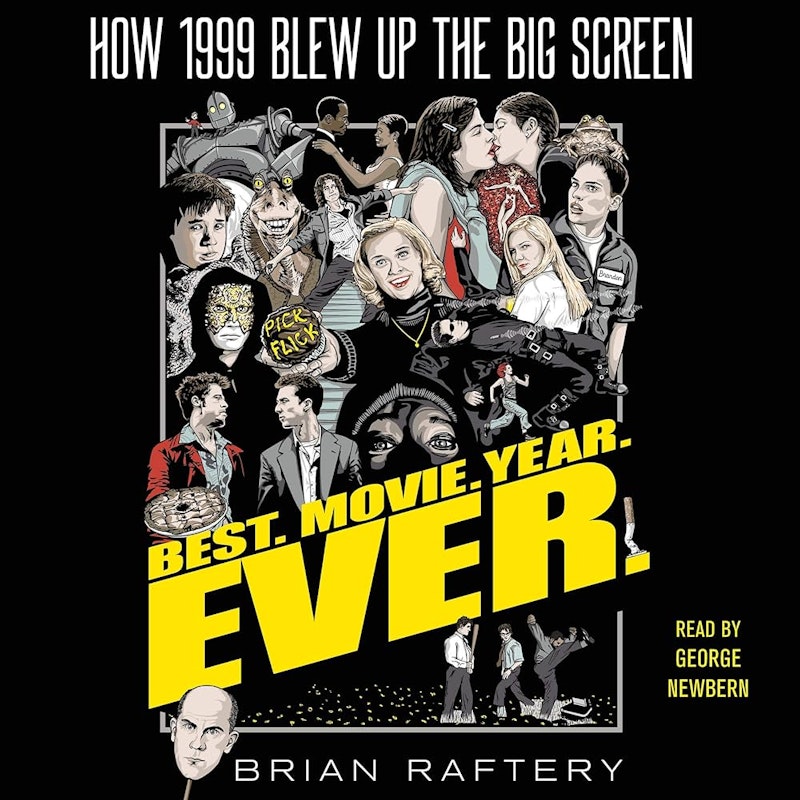

Four years ago, Brian Raftery released a book on 1999 called BEST. MOVIE. YEAR. EVER. It had the good-bad luck of coming out in March 2020 right when the pandemic hit—I hope a lot of people read or listened to it back then. Raftery’s book is excellent, surveying most of the movies listed above and going through their development, production, release, and long-term cultural significance and impact. So many of these movies are still so famous and well-known that I don’t need to elaborate—you all know what The Matrix, American Pie, Fight Club, Office Space, and The Blair Witch Project did.

There aren’t many movie books covering relatively recent history as well as Raftery’s; everyone’s still obsessed with the 1960s and the New Hollywood of the 1970s. Raftery calls Peter Biskind’s 1998 book Easy Riders, Raging Bulls “seminal,” and unfortunately it was, because people can’t stop writing about the fucking late-1960s and early/mid-1970s. I can’t wait for Bret Easton Ellis’ movie book, teased as a collection of essays similar to Quentin Tarantino’s Cinema Speculation but covering “poppier, glossier” films of the late-1970s and early-1980s, with some overlap.

Something I valued in Raftery’s book was its cultural analysis, articulating and contextualizing the anxieties and controversies of pre-September 11 America. He astutely points out in his introduction: “While the 1990s would later be revised by some as a sort of pre-9/11 paradise [ED: It was], the period had in fact been marked by social and political tumult.” But compared to the “perpetual” miseries of our current century, “the beating of Rodney King, the battle over Anita Hill, and the bombing of Oklahoma City” wasn’t too bad. If you were King, Hill, or a resident of Oklahoma City, different story—but this century has brought chaos, disaster, and apocalypse to everyone’s home, culminating in the panoptic pandemic.

American Pie’s “MILF Guy #2” and future Harold & Kumar star John Cho observes, “You don’t really go to movies for ideas anymore or to get challenged in the way that you used to. They’re more like bedtime stories: you know what you’re going to get, and you use it to get a particular feeling.” Steven Soderbergh goes even further, offering, to me, a profound insight: “I think 9/11, in a very subconscious way changed the reasons people go to the movies. It’s an event the country still hasn’t processed or healed from, and without anyone saying it out loud, this sense of ‘Well, you go to the movies to escape’ really increased. People have always gone to the movies to escape—but after 9/11, that feeling really took hold.”

He’s right on both counts: you can find mild variations on Cho’s comments going back decades, whether it’s Lucille Ball in the late-1970s bemoaning how sleazy the movies had become, or Warren Beatty in the mid-1990s rhetorically asking Peter Bogdanovich and Henry Jaglom, “What happened to John Ford? What happened to Gary Cooper? Do any of these kids know them?” But the September 11, 2001 attacks were as much of a revolution in our perception of images as the invention of the television itself. It’s more significant than the introduction of color. “9/11,” the memetic container for all 21st-century misery, was a movie—that’s how nearly everyone in the world experienced. My family and I lived through the September 11, 2001 attacks and their endless aftermath, but more than that, we’re haunted by the images of the ritual blood sacrificed carried out in our back yard, broadcast and replayed to all the world in living color and high definition. When life looks “just like a movie,” what can the movies do?

—Follow Nicky Otis Smith on Twitter and Instagram: @nickyotissmith