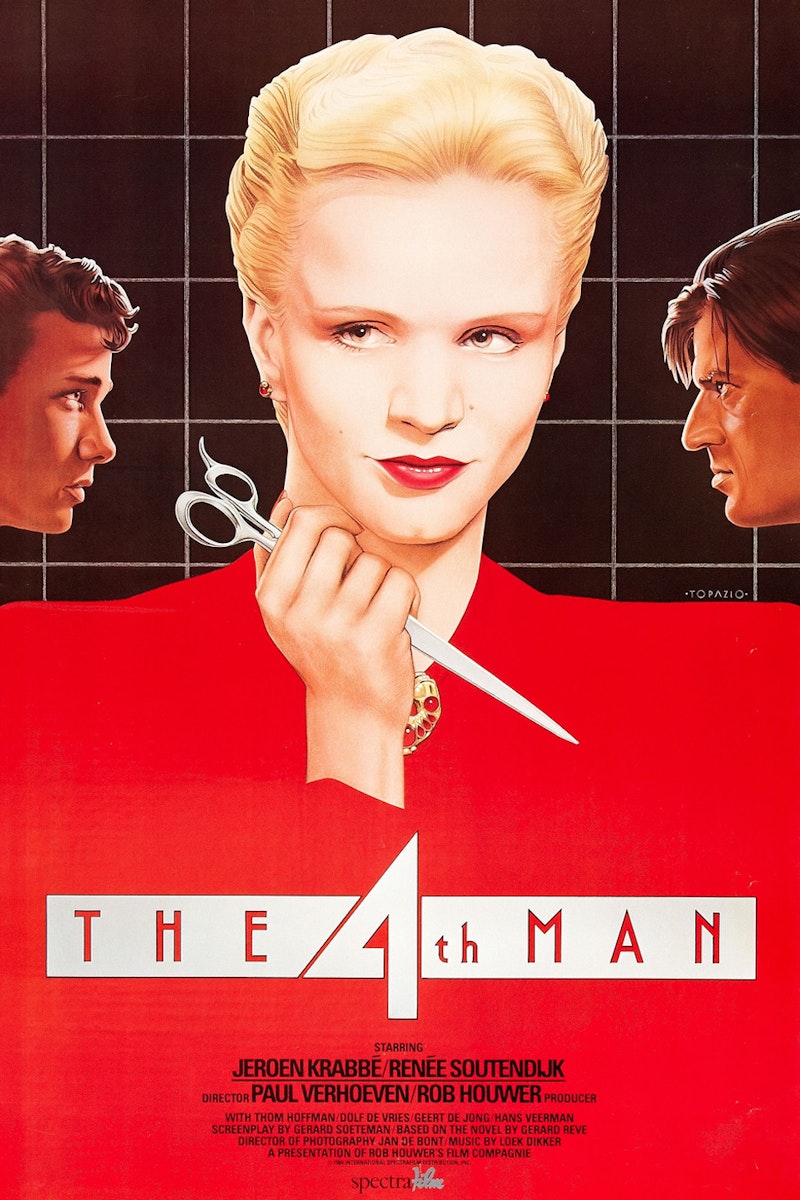

During the darker parts of winter I find myself reverting back to a childhood raised by the History Channel, reaching for programs on ancient conspiracies and/or movies about WWII. This year one of my finds was Paul Verhoeven’s 2006 film Black Book, which, despite being the most expensive Dutch movie ever made at the time as well as one of the highest grossing, has seen little recognition among US fans. This led me to pursue more of the early Dutch-language work that shaped this childish and academic renegade into a juggernaut of Hollywood genre film in the 1980s and 90s. One of my most surprising discoveries is his last movie before heading to L.A., one that seems like a keystone to such disparate wings of his filmmaking, from Basic Instinct to Benedetta.

The 4th Man opens with a spider weaving its web on the back of a crucifix. Lying on the bed in a desolate room, with his shirt on and cock out, is Gerard Reve. He’s a writer, a Catholic, an alcoholic, and a repressed homosexual. In a hallucinatory opening, we see a violinist bathed in glowing morning light mock the old drunk as his shakes keep Reve’s hands from shaving. Reve reaches for a bra and strangles his maybe-lover, then snaps back to reality. Reve tells the man he has to depart for a small town to give a lecture. On the train he falls into visions yet again as a woman and child get his attention, and he seemingly walks into an advertisement above them, an art-deco hotel that turns into a nightmarish omen when a peephole becomes a dislodged eye. Blood drips out of the photograph, or, it’s just tomato soup. Death has started to stalk him, or at least that’s what he thinks. On the train platform he sees men carrying a casket, he thinks he sees his name on it. One of the carriers smiles and unfurls the ribbon to show him that it doesn’t say “Gerard” but “Guido Hermans.”

Gerard’s driven to his lecture by Dr. de Vries (whom he’ll meet again later in the film in a completely different light), who explains it’ll be mostly old people attending, not an exciting crowd but very interested. Coming through the doors a figure in red immediately pops against the drab suits in the background. Christine Halsslag grabs our attention in the corner of the frame like Kim Novak first appearing in Vertigo, although with the voyeurism reversed—she holds a 16mm camera in her hand like a gun. By the time Gerard asks Christine if they will sleep together that night, the answer is already as clear to the audience as it is that something’s amiss. When they arrive at her house, the glowing neon sign reads “SPIN” (Dutch for “spider”). No, the sign is just malfunctioning, it really says “SPHINX.” Maybe at a glance more comforting for Gerard, the sphinx being that great and wise protector of Egypt and her people. Although, soon it’ll seem much more like the sphinx of Greek mythology, that winged lion and symbol of womanly wrath.

Christine’s house is also her business. She runs a salon (also a pun?), and her beauty product label “Delilah” has made her wealthy. The Biblical reference, again, makes it seem inevitable that Christine will cut his hair, but in a Verhoevian twist, Gerard also envisions her cutting his dick off, his most crude source of masculine power.

The story of Samson and Delilah is theoretically much older than the Old Testament itself. Some scholars have postulated that the supernatural masculinity of Samson harkens back to ancient Greek demigods, or more likely, the wildman Enkidu from the Epic of Gilgamesh. Delilah’s role in Samson’s story involves some of the most classically misogynistic hermeneutics in the Judeo-Christian canon, rivaled only by the interpretation of Eve as the original betrayer of mankind. Samson’s one of the most important figures in the struggle between ancient Israel and the Philistines. They send Delilah to seduce Samson and find the source of his power, who he continually conceals from her, before he reluctantly reveals that his hair gives him strength. She cuts his hair and sends the Philistines upon him. It’s a legendary parable of mistrust, telling the insiders not to trust the outsiders, men not to trust women. For Gerard, this conclusion drives him to a paranoid insanity.

But while his paranoia grows, so does his obsession. Not with Christine, but one of her lovers, Herman. Seeing a photo of him he realizes he shared a passing glance with the man at the train station, and looking at his statue-like body he immediately begins to weave his own web to try to get Christine to lure Herman his way. His lust is contradicted by his unyielding Catholicism, although Verhoeven seems to think this contradiction may be inherent to the faith itself—with its grotesque and violent imagery bringing forth a certain kind of eroticism, and the image of the sacrificed man given into his fate can be a kinky idea. Maybe in the most perverse and sexually iconoclastic movie scenes since Ken Russell’s The Devils, Verhoeven shows Gerard fantasizing about Herman on the cross, ready to pull his garment down right before he’s interrupted by an old woman at the church who’s horrified that this man is kissing a statue of Jesus.

Laura Mulvey once described analyzing Godard’s cinema as a “goldmine” for “feminist curiosity,” wherein a “deep-seated, but interesting misogyny… knows its own entrapment.” And whereas Godard’s films have often been an investigation of investigation, whether political or cultural-mythological, I think Mulvey’s analysis could be transposed onto Verhoeven’s works, not through any didacticism or analytic structure, but by way of their showcasing how cultural and sociopolitical phenomenon manifest in experience and psychological subjectivity. And just like some of his best films, whether Hollywood erotic-thrillers or European chamber dramas about the nature of faith, Verhoeven leaves no clear answers—all the characters can do is either accept things as a coincidence or believe that everything is a pattern and imbued with meaning.

But why is it called The 4th Man? If you haven’t seen it, all I’ll reveal is that “man” is yet another pun in Dutch. All these years later, Paul Verhoeven’s last movie from his home country for over two decades still stands today as one of his most fascinating and cheeky films.