“In Germany we have regressive summer movies about young people who study in Berlin and come back to their parents for the summer and say ‘Mama, I’m homosexual.’ The whole movie is about this. Or the father and mother want to divorce and the 31-year-old son is getting depressed. I mean, this is not a story… I like that in French and American movies, the summer is not only a season––it’s something where you learn something about yourself. In many of these movies, bad things can happen, but the movies themselves are like summer. It’s the wind, the water, the bodies. It’s light, and they are light and elegant. This: this I like.”—Christian Petzold, Interview with Film Stage.

Cinema thrives in the sensory delights of changing seasons: the amber hue of New England fall that Jean-Yves Escoffier lensed so lovingly in Good Will Hunting; the slushy melancholy of Pittsburgh’s winter in Wonder Boys; the late Chicago springtime of Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, in which every character is still dressed in long sleeves or a jacket, as is so often necessary in spring there. But the summer is unique in its languid pace. As temperatures increase, everything slows down. People take time off work and lay in the sun or, when the heat is unbearable, in air conditioning or the near radius of a box fan. They sweat, they swim, they dance, they smoke. They start going out more and, near the summer’s end, they get sick of going out. In July, the sparklers sparkle, the sprinklers sprinkle. On August afternoons, the bricks of the tallest buildings glow in the low sun. Cars die in the heat, which rises from the asphalt in inferior mirages until a storm front or cracked hydrant cools it down. All of this is ripe for cinema.

As the ocean boils over into a different kind of Endless Summer, let’s stay positive and relish these summerly pleasures, if not outside on the beach or in a swimming pool then at least in the frigid AC of the movie house. If you’re lucky, your local theater revived one of these contemporary summer classics.

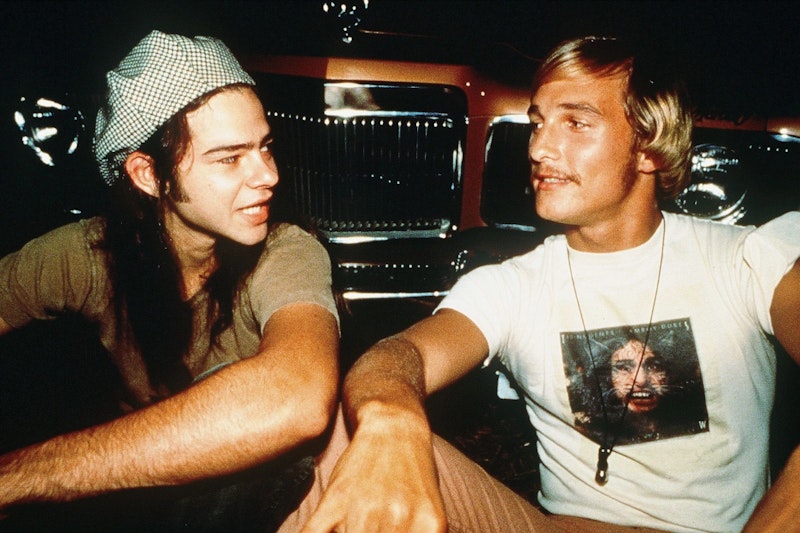

Dazed and Confused (1993, Richard Linklater): The mack daddy of summer movies technically takes place in May, but summer arrives early in Texas. The summer of Dazed and Confused is less a season than a rite of passage. It’s highly possible Petzold was thinking of it when he said that kids in American summer movies learn something about themselves. Linklater takes a fairly low stakes decision—whether or not to play football in the fall—and turns it into a full-scale existential dilemma for Randall “Pink” Floyd (Jason London). Yet unlike American Graffiti (the obvious model for Dazed), the conflict never feels heavy, partly because we know he’ll have three months of Aerosmith concerts and cruising around with his friends to think it over. While Pink quietly debates his future, Mitch (Wiley Wiggins) is content to settle into life as a high school athlete and avoid any additional paddling from the rising seniors. For Mitch, the three months will surely feel longer, the road to self-discovery bumpy with ass welts.

Smooth Talk (1985, Joyce Chopra): Most summer movies, especially those about young people, lean heavily toward the male perspective. In these movies, summer’s a time of freedom, a time to test the limits of curfew and wander further from the nest. Smooth Talk, on the other hand, is about a teenage girl named Connie (Laura Dern). Connie does what teenage girls do during the summer: she swims and cruises the mall with her friends, argues with her mom (Mary Kay Place), and spends a lot of time bored around the house. The movie’s plot centers around the unwanted attention of an older suitor (Treat Williams) and Connie’s own self-discovery, but for me, the most memorable moments are the little ones where Connie isn’t doing much of anything. In what might be the most vivid expression of summer boredom ever committed to film, Dern leans her tall frame against a wall at one point, then pushes herself off, shifting momentarily in the opposite direction before letting her weight fall back again. She repeats this motion a few more times, as if tethered to the wall. It’s a very small, blink-and-you’ll-miss-it moment, but when I think of Dern’s superlative talent, it’s the image my mind returns to. In one tiny gesture, she embodies the stagnant air of late summer.

Stand By Me (1986, Rob Reiner): When I caught a revival of Stand By Me at the Senator last month, I was pleased to see some parents bring their kids. Despite its R-rating, it’s a good movie for kids to see when they’re young—maybe not at six years old like me, but definitely before middle school. When I was a kid, boys were socialized to either be macho or funny. Sensitivity and vulnerability were not widely accepted in the male gender, especially given the era’s rampant homophobia. (I remember a friend saying Stand By Me was gay because the characters sing together.) Aside from being another great summer movie about self-discovery in adolescence, it’s a movie that allows its male adolescent characters to be sensitive and vulnerable with each other. When Gordy (Wil Wheaton) tells Chris (River Phoenix) that he hates writing and doesn’t want to do it anymore, there’s something almost unbearably touching in Chris’ response, which begins in outrage (“Bull true!”) and ends in heartfelt encouragement for his friend. The same is true of the way Gordy hugs Chris while he cries by the campfire (something about campfires really brought out the vulnerability in Phoenix). All four central characters cry by the end of the movie, and their friends don’t ridicule them for it. Reiner pointedly contrasts this behavior with the older delinquent boys, who are depicted as violent, destructive and cruel, constantly cutting each other down in hypermasculine competition. Stand By Me is about the death of innocence, but it’s also about carrying a small shred of that innocence into adulthood through compassion and empathy. I can’t think of a better movie to show a kid.

The Sandlot (1993, David Mickey Evans): The Sandlot is kind of like Stand By Me Lite, but it gets so much right about summertime with the boys, I had to include it. I especially like the way it starts off with a nerdy kid’s mom encouraging him to go outside and make friends (extremely relatable). The friends are all sort of skeptical of the kid, but the one cool kid who everyone looks up to gives the nerd the green light, so he becomes part of their little makeshift baseball team. They do a lot of summer stuff, like go to the pool and a carnival, but it’s mostly about those hot afternoons playing baseball as the shadows from the street lamps move slowly across the lot. Pop flies evade sunblind outfielders. A beloved autographed ball lands in the mouth of a massive hellhound. James Earl Jones saves the day with some Deus Ex Memorabilia. This is what summer with the boys is all about.

Menace II Society (1993, The Hughes Brothers): Menace II Society takes a very confrontational approach to the summer-after-graduation movie. While the white teens of summer movies work as lifeguards and go to camp, the black teens of South Central Los Angeles are mostly just trying not to get killed. Menace opens with the horrific double murder of a Korean couple, followed by a darkly comic punchline in the film’s narration: “After that, I knew it was gonna be a long summer.” This is the movie’s primary tactic—unpredictable eruptions of casual violence that shake the viewer’s senses, followed by an ironic punchline or joke to underscore the nihilism—and it’s brutally effective. Yet as shocking as Menace’s violence is to this day, the South Central depicted is a place where summer’s eventual boiling over into violence is practically inevitable, as Ronnie (Jada Pinkett Smith) continually tries to tell Caine (Tyrin Turner). The ending, where Caine’s murdered in a drive-by shooting just before he’s set to leave LA, never hits quite as hard as it should, maybe due to the numbing effect of the preceding 90 minutes. But it still functions as a solid rebuke to American Graffiti’s Vietnam-related postscript. The graduates of Menace II Society don’t need to go off to war to senselessly lose their lives.

Do the Right Thing (1989, Spike Lee): Do the Right Thing is probably the best movie on this list. It’s easily the one that best captures the misery of a heat wave (though an honorable mention should also go to Lee’s underrated Summer of Sam) and the lengths in which we go to for relief, like rubbing our loved ones with ice cubes. Like Menace II Society, it also shows how the summer heat can boil over into violence, but unlike the young, eager to impress Hughes Brothers, Lee takes his time. He gives us one day in Bed Stuy, mainly following pizza delivery guy Mookie (Lee) and his Italian boss Sal (Danny Aiello). (As someone who has worked in multiple pizza kitchens, I can confidently say there’s no place I'd less rather be in the summer months.) Racial tensions fester in the unforgiving heat. People start to lose their minds. Even the level-headed Mookie eventually caves and throws a trash can through Sal’s window. What’s compelling about the summer of Do the Right Thing is how central the simple pleasures of the season become to the film’s broader themes on race and social justice. For example, all Radio Raheem (Bill Nunn) wants is to play his boombox, a harmless enough way to pass the time on a summer’s night. He ends up dead for it. Simple pleasures are always under threat for black people, Lee seems to be saying. The most innocuous summer rituals can still carry deadly consequences.

Adventureland (2009, Greg Mottola): When Adventureland was released, America was still in the throes of Apatow Fever, not let down by Funny People just yet. Miramax therefore marketed the former with a certain Apatow flavor (“from the makers of Superbad”) that undersold the movie’s strengths. Except for an ongoing gag in which the protagonist (Jesse Eisenberg) is repeatedly punched in the balls, the juvenile, scatological humor of Apatow’s work is largely absent in favor of a slightly more refined sensibility. There are lines that recall a young Noah Baumbach (“I majored in Comparative Literature and Renaissance Studies, unless someone needs help restoring a fresco, I'm practically useless”), delivered by Eisenberg with his characteristic anxious motormouth. Even more impressive is the brilliantly cast Ryan Reynolds as a pathetic repairman who regales the female employees of the titular amusement park with clearly fabricated stories of jamming with Lou Reed. Adventureland is about wasting away the summer after college in a shitty, low-paying job, and it gets everything right: the awkward crushes, the nightmare soundtrack (great use of Falco), the sad coworkers who are around long after you quit, the need for marijuana just to get through the boredom. The summer becomes symbolic of youth itself, whose preciousness is intimated in the subtlest of ways—a quiet ride home with someone you like, or staying up to watch the sunrise—and only to be made sense of in retrospect.