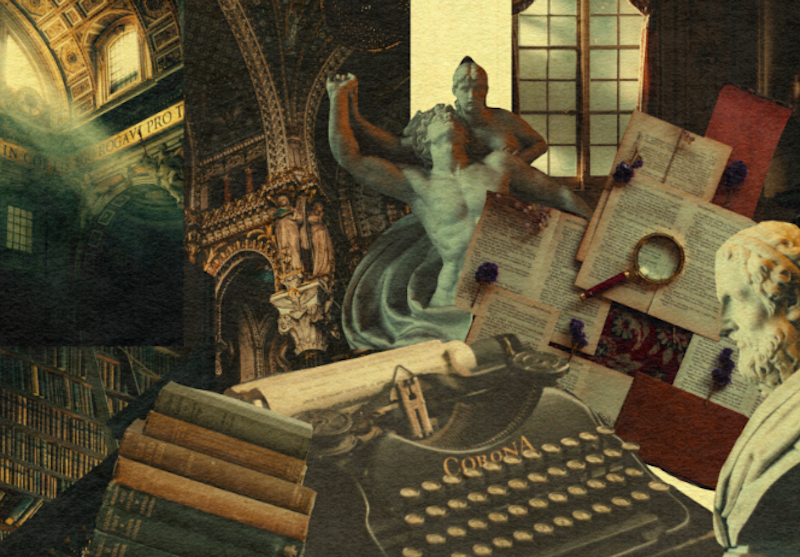

Over the course of the pandemic, I stumbled into an online subculture that’s as charming as it’s disturbing: dark academia, best described as a loose consortium of social media devotees committed to a love of reading and learning, and an appreciation for vintage clothes and decor. The preferred music is classical, best for long stretches of studying. If there’s a goal, it’s to lead a pleasurable life of fine arts appreciation and intellectual heavy lifting, and to look good doing it. This has been burbling on Tumblr for several years, but with the school closures, many students saw it as a way to break up their isolation without leaving the house, as well as a broader reevaluation of what education means to their lives.

Despite criticism of material snobbery, many of these young adults are working with the finances they actually have. Thrifting and crafting are common hobbies—even if one can’t attend an elite university, it’s possible to find inexpensive used copies of Mozart and Aristotle, and some nice loafers. The crafting isn’t entirely about budget constraints, it’s also way to reconnect with a more hands-on way of life. A post-digital generation raised on Harry Potter and Wes Anderson films have developed a curious nostalgia for the analog world.

There are curated lists of movies and books that are viewed as cultural touchstones. Frequently cited are films like Dead Poets Society, School Ties, The Riot Club, and Kill Your Darlings. Most significant is the unintentional guidebook for the movement, Donna Tartt’s 1992 debut novel, The Secret History, a why-done-it murder mystery with some homoerotic subtext sprinkled about.

What makes The Secret History so appealing is the aspirational fantasy it presents: an elite clique within an elite New England school and Tartt’s descriptions of what they wear and how they live. Then there’s the storytelling itself, where we learn on the first page who was murdered and by whom, but we don’t know why. As the story plays out, Tartt ponders the morality of this level of elitism, that perhaps when knowledge is kept at such an advanced level of gatekeeping, the ones most stripped of their humanity are those cloistered within its walls. Tartt has cited Alfred Hitchcock for how she crafted the tension: “Suspense doesn’t come from having a bomb thrown at the hero. Suspense comes from having two people, sitting, talking at a table, there’s a bomb ticking underneath the table—the audience sees it, but the characters do not.” In the context of The Secret History, it sets the stage for exposition through existential crisis, almost akin to The Tell-Tale Heart or Crime and Punishment.

One other aspect of The Secret History’s renewed appeal is Tartt’s own backstory, and the inspiration it provided. Transferring from the University of Mississippi in 1982 to Bennington College, her classmates included future novelists Bret Easton Ellis and Jonathan Lethem. Not all would graduate, but Tartt and Ellis in particular became very good friends, with her dedicating The Secret History to him. It’s interesting to consider how she amalgamated people she knew into the story, given that the narrator is himself a transfer student from a more middle-class background than his affluent classmates, a description that can be applied to both Tartt and Lethem. The interest in this microcosm of literary history has inspired the podcast, Once Upon a Time…at Bennington College, and its accompanying Esquire article. A Town & Country article explored that. Even Courtney Love has suggested that she’d have been a student at Bennington in 1982, if only she had listened to her probation officer. It seems everyone wants to be a dark academic.

Another criticism is that dark academia could be a bad influence on kids, which might have some merit. The Secret History is not a YA novel. The book is popular enough to suggest that its young fans are more precocious than they’re given credit for. However, its depictions of sex, violence, and substance abuse as metaphors for character decay are rough on the uninitiated youths. Although, as someone old enough to remember when you could still smoke cigarettes at the mall (back when we still went to malls), it’s amusing to see today’s teenagers appalled at how much college kids smoked in the 1980s. That said, I fear the unintentional lesson kids might be learning is to use the veneer of higher education and intellectualism as a mask for undeserved elitism. Nowhere is that clearer than in a particular storyline from Riverdale, the noir teen soap update of the Archie comics.

Riverdale has become a source of Internet fascination because of its crazy writing. No one admits to liking it, just that we can’t look away from the car crash. The show’s attempts at paying homage to Twin Peaks and The Silence of the Lambs can be diverting, but when it took a turn toward The Secret History, it looked more like a prolonged grudge match, stoned on its own pretentiousness. The real problem is that the show tries to cram too much into one storyline, and collapses under the weight of it all. It’s clearly making an appeal to the dark academics in its audience, while trying it’s hand at every sub-genre of mystery. It even goes so far as to try to borrow its format from Memento, the Christopher Nolan film that reveals its mystery in backwards and forwards story arcs until they converge in revelation. In the context of a weekly teen soap, which usually has multiple storylines, shifting around in time is more than the format can handle. But worst of all, the show’s sense of integrity is so warped that even its heroes are nearly as amoral as its villains, and is violent for a show aimed at teenagers and middle schoolers.

Yet Riverdale remains overly pleased with itself, to the point that when Jughead was preening through the conspiracy-laden reveal, I was disappointed his would-be killers hadn’t finished the job. It was as though the writers were using his voice to congratulate themselves for their cleverness. And given that Riverdale was created and run by a Yale-educated playwright, it’s exactly the sort of undeserved elitism masked by Ivy League credentials that smarts the most.

Aside from material elitism, the other significant criticism is that dark academia is a celebration of whiteness. In fairness, it does seem inevitable, if unintentional. I think there’s some legitimate concern, especially as white nationalists like to exalt Western culture as a kind of gateway drug to racial prejudice. As I’ve seen bloggers and YouTubers swap reading lists, I’m not especially concerned, because the dark academics themselves aren’t all white or heteronormative. Because the demographic shift of people born after 2000 gradually getting less white with each year, and more racially diverse, which is increasingly reflected in various online subcultures, and it shows in some of their reading choices. Social media has also made dark academia enough of a global phenomenon that people are recommending books from their home countries, which sits well in a larger interest toward more international reading.

Dark academia reminds me of 90s goth culture, despite the obvious wardrobe difference. The way outsiders worry that dark academics are snooty white supremacists is reminiscent of the fear that goths were Satanists, when all the kids want is to be left alone to read Byron in the moonlight. The young people that like to read are usually the kids that should be the least cause for worry. The children whose educations have been irretrievably damaged by the pandemic’s interruptions, making them vulnerable to gangs or just street life in general, are the ones who should be the concern of worrywarts.

The one thing I most respect about what young adults and teenagers are doing with dark academia is reinventing humanities appreciation. As college tuition has, for decades now, outpaced inflation, students are taking a more utilitarian approach to higher education. Liberal arts and humanities majors are declining in favor of business and STEM fields, so the dark academics aren’t just reading Homer and visiting museums on their own time, they’re taking their intellectual ambitions seriously. The goals are best expressed by the Robin Williams character in Dead Poets Society: “We don’t read and write poetry because it’s cute. We read and write poetry because we are members of the human race. And the human race is filled with passion. And medicine, law, business, engineering—these are noble pursuits and necessary to sustain life. But poetry, beauty, romance, love: these are what we stay alive for…That you are here—that life exists, and identity; that the powerful play goes on and you may contribute a verse. What will your verse be?”