It would be a shame if potential viewers were turned off by the seemingly insular Jewishness of the Coen Brothers' new film A Serious Man, since it may very well be the directors' most universal film. Untethered to any specific genre, much less violent than their typical work, and less aesthetically aggressive than some of their other films of this decade like Burn After Reading and The Man Who Wasn't There, A Serious Man is also a rare contemporary film that addresses religion without demeaning its practitioners. The Coens' methods, from their gleaming cinematography to their theatrical characterizations, remain un-trendy, even anachronistic, and their new film disproves once and for all the accusations of nihilism that have unfairly reoccurred in criticism of their work. A Serious Man is imbued with loving, purportedly autobiographical detail, and is the most emotionally rich film yet from two filmmakers whose work has always been so.

The film begins and ends elliptically. We're first treated to an eerie Yiddish-language prologue worthy of Isaac Singer, where an eastern European couple is visited by an elderly man. He may be a ghost as the wife believes, or he may be the harmless villager he claims to be. In either case, they cast him out and life goes on; the scene ends with the couple wondering what the outcome of their actions will be. We're invited to read this little parable as somehow the beginning of a curse, one that implicitly winds its way through the generations to Larry Gopnik (Michael Stuhlbarg), a physics professor in a Jewish Minneapolis suburb in the late 1960s. But I'm more inclined to view it as a sort of folk tale about the persistence of unknowing—an inclination that's strengthened by the film's haunting final images, of literal and figurative gathering storms, that occur after the long suffering protagonist finally experiences some degree of happiness.

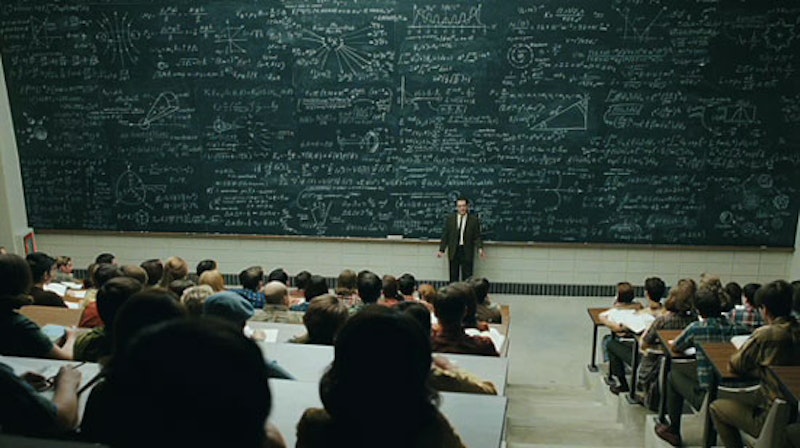

At the outset, however, Larry's marriage is ending, his children have no visible respect for him, his shot at tenure is uncertain, a student is seemingly blackmailing him after a test, and his schlemiel brother Arthur is sleeping in the living room with no plans to move out. Despite initial appearances, the Coens' characterizations are too multi-faceted and Larry is afforded too much dignity for this premise to seem overly cruel or one-sided; as always, Roger Deakins' photography hugs the landscape and the perfectly art-directed interiors, and even the smallest walk-on roles make an impression.

Most impressively, A Serious Man rivals Fargo in its depiction of not only a time and place, but of the necessarily homogenized attitudes and behaviors of people who live near one another. The religious context in the newer movie adds a different layer of resonance, of course, and the Coens convey—without ever succumbing to easy ethnic jokes or tired Woody Allenisms—the odd mix of pride, paranoia, and self-pity that groups of Jews often feel. This is a complex, deeply felt representation of Jewish identity, and more so because of the setting. It's refreshing and foreign to see Jews occupying this geologically flat Midwestern milieu, to see them striving for stereotypically gentile goals—a ranch-style house, a neighbor who respects the property line—without the writers playing this incongruity for laughs. The Coens still populate their film with strange-looking faces, and here they display an almost fetishistic focus on inner ears and scraggly rabbinical facial hair, but their representations of human behavior have an honesty and sense of realism worthy of Altman, Fellini, or Ford. We recognize ourselves in the looks on the character's faces, in their reluctantly perseverant response to family crisis, and in their barely-composed interactions with co-workers.

Much of this realism stems from A Serious Man's treatment of religion. I have no religious inclination myself, but I still blanch at the reactionary, dismissive treatment of faith in recent films like The Invention of Lying. Disbelieving the tenants of any religion doesn't make that religion go away, and the Coens manage to express why and how people live with religion without ever validating or even passing any judgment on faith itself. (They do satirize, brutally, many people of faith, but in the same self-identifying way that they mocked writers in Barton Fink and Americans generally in nearly all their films.) It's the same artful balance that Jonathan Demme achieved last year in Rachel Getting Married, and also the primary source of emotional resonance in McCabe & Mrs. Miller. When a friend tells Larry that he has "a well of tradition" to look to in times of trouble, the sentiment isn't meant as a punchline, as it so often is in Allen films. Gopnik takes it seriously, as many people do, and the fact that religious traditions offer no immediate answers or solutions only adds to his dismay. But while he may not achieve any spiritual comfort from the Torah or from the sequence of befuddling rabbis he visits, there is a surprisingly, disarmingly touching scene near the film's end where his son's bar mitzvah occasions a moment of true pride and happiness. The Coens understand how religion gives meaning to people's lives through ritual and sacrament as much as belief and myth.

This is the most overtly autobiographical of the Coens' movies, though not just for reasons of ethnic and geographical detail. (Scenes of Larry's son sneaking pot in his Hebrew school bathroom are rendered with loving familiarity, though.) Rather, I couldn't help but marvel at the relationship between Larry and his ne'er-do-well brother Arthur (Richard Kind), which forms the spiritual center of this improbably gorgeous film, just like the Dude and Walter's friendship lends emotional heft to The Big Lebowski. Arthur's socially crippling goiter and general haplessness is played mainly for comic relief throughout A Serious Man, while our sympathies lie mainly with the increasingly despondent Larry. But Arthur finally reaches a breaking point, and in his despairing state expresses anger that god would deal him such a bad hand. He's jealous of Larry's normalcy-his family, his house, his career-and has been experiencing the same Job-like state of affairs for nearly his entire life. The acting in this scene is brilliant and underplayed; Larry's sense of tragedy is clearly as shaken as ours, and we share his sudden reorganization of emotional priorities. If religion ultimately gives Larry's life order and purpose, family is what ultimately gives it meaning. Neither brother wonders if god exists—they wonder how god's presence can be felt amidst self-pity and disorder. The Coen brothers manage to make this theme felt without ever veering into sentimentality or losing their sense of humor, and the result is one of the most honest and affectionate films about religion that I've ever seen.

In the last 10 years, from O Brother, Where Art Thou? to A Serious Man, these directors have made an astonishing run of films, in styles as varied as screwball comedies, westerns, near-musicals, and noir. No other American filmmakers have done so much with the medium over the same period of time, just as few others have observed the subcultures and behaviors of American people so closely. As a film enthusiast, I feel almost privileged to be alive while the Coen brothers' incredible career continues to wind and develop. Astonishingly, they're only getting better. A Serious Man is their most mature, soulful movie yet.

A Serious Man, directed by Ethan Coen and Joel Coen. Focus Features, 105 min., rated R. Now playing at the Charles Theater.