“Anarene, Texas, 1951. Nothing much has changed…” The only better tagline to come out of the brief but candescent New Hollywood was the one for Easy Rider: “A man went out looking for America, and couldn’t find it anywhere.” Besides the phrase “went out,” it could easily apply to The Last Picture Show, an inimitable masterpiece that the late, great Peter Bogdanovich never came close to topping. Like his idol and friend Orson Welles, he went on to make many more wonderful films—I prefer 1981’s They All Laughed—but the ineffable power of The Last Picture Show isn’t even suggested anywhere else in his work. Bogdanovich largely made comedies, with a couple of early exploitation films (1968’s Targets is particularly good), and work-for-hire surrounding a handful of movies that should be put into time capsules.

I first saw The Last Picture Show as a teenager, encouraged by my dad, who remembered the afternoon he saw it by himself in the spring of 1972 and walked around for an hour afterwards in a daze. So much of it mirrored his own life, explicitly and implicitly, and the sound of Hank Williams wafting in from houses, cars, doorways, always diegetic, never a “score” until the end credits—and the wind, and the tumbleweeds. Everything is gone. But more than any other scene in The Last Picture Show that hit him was Sam the Lion’s (Ben Johnson) speech to the boys after they’ve taken deaf-mute Billy to the town prostitute so he can lose his virginity (“Make sure he gets some pussy before he dies”). Teenage boys get carried away and when they bring back Billy to Sam’s, his nose bloodied and his nerves shaken, Sam tells the boys they’re no longer welcome in his pool hall, cafe, or the picture show: “I’ve been around that kind of trashy behavior my whole life and I’m getting tired of putting up with it… You didn’t even have the decency to wash his face.”

The Last Picture Show is a film defined by grace notes: Sonny (Timothy Bottoms) turning Billy’s cap around, Duane's (Jeff Bridges) delivery of the line “I ain’t over her yet” at the end, Duane asking Sonny if he’s still going with Jacy (Cybill Shepherd) and Sonny’s delivery of his reply: “No—yeah, I guess… sometimes we go and eat Mexican food,” Coach Popper ignoring Sonny at the end after he’s cuckolded his wife Ruth (Cloris Leachman), Sonny’s dad appearing in exactly one shot of the movie where they say hello and goodbye, and the way the camera turns on Ellen Burstyn after Sonny asks her, “Nothing’s been the same since Sam died, has it?” Things happen in The Last Picture Show, but in a year, nothing much has changed… and you can feel it never will. Sonny’s attempted “escape” out of Anarene toward the end feels like something out of Antonioni, and while the film is on the surface indebted to John Ford more than anyone, it has the aching sadness and dull hopelessness of contemporary European films.

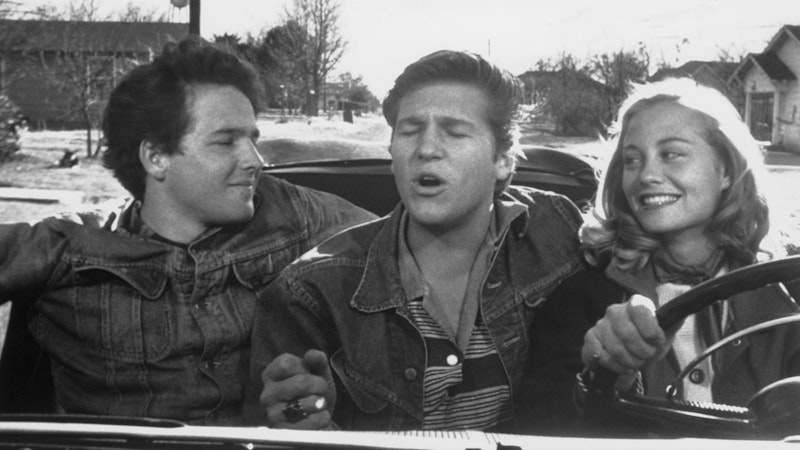

I saw it with my dad early on a Saturday, then on Monday with my cinematographer, then last night by myself. Every single time, something else sticks: now it’s Duane, Jacy, and Sonny singing “Anarene, high school, we love you” in the car near the beginning. The way Sonny denies seeing Ruth Popper anymore (“No, yeah…”), and the way that he remains completely passive until Billy’s killed. Besides his fight with Duane, it’s the one time he raises his voice—otherwise, Timothy Bottoms imbues Sonny with the soul of a poet, always observing, his eyes completely vacant and containing everything, at once. Everyone in the town feels like a ghost, and it obviously feels like a ghost town, with its mirrored opening and closing shots, a closed circle that you can still revisit regularly throughout your life, just to see how all these ghosts are doing.

—Follow Nicky Smith on Twitter: @nickyotissmith