It’s not easy to create a well-executed heist movie. Much like a robbery, it requires precision, perfect timing, and elegance. Henri Verneuil’s 1963 crime drama, Any Number Can Win (currently streaming on the Criterion Channel) succeeds in all three aspects. Any heist movie also requires star power, and that’s the case here as well, with Jean Gabin and Alain Delon in main roles.

Gabin plays Charles, an older man, who just got out of prison. His crime specialty is robberies, and he wants to do one last heist before he “retires” in Australia. His wife, who’s surprised at his return (somehow, she didn’t realize he’d be coming back home that particular day), has had enough. Although she still loves him, she doesn’t wish to continue being an accomplice. But Charles disregards her wishes, and presses on. He has, as he says, one more heist in him.

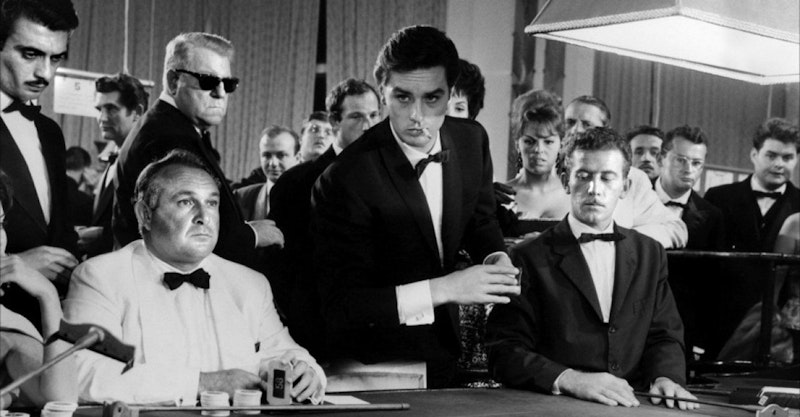

An older man, Charles is unable to complete the more physical tasks of the robbery (like going through the air ducts and elevator shafts to get to the safe), and so he persuades Francis (Delon) to join him. The plan is to rob a casino on the French Riviera. They’re joined by Charles’ brother-in-law, who serves as the driver, but has moral qualms about the operation. The plan is set in motion: false identities, separate arrivals to the hotel, development of relationships with women who might be useful, securing a pool room that’ll serve as a dumping place for the stolen money.

Everything goes well—for the most part—until Charles sees Francis’ picture in the paper. Although his identity isn’t entirely known to the police, Charles thinks it’s a risk for him to be seen around the grounds of the casino and hotel. He tells him to bring the money to the swimming pool so that he can hide it elsewhere. The plan is for Francis to get his share later. But the final twist puts this film in a unique category of heist films.

Unexpectedly, the police are milling around the swimming pool, trying to put the pieces together in order to catch the robbers. The casino owner, Grimp (José Luis de Vilallonga) is talking to the police. He’s unable to identify either Charles or Francis because they were disguised, but has an impeccable memory of the money bags. Francis is quietly listening to Grimp’s perfect description of the bags, as he pushes them closer and closer to his legs.

On the other side of the swimming pool is Charles waiting for the money. Francis is visibly anxious, despite the fact that the police and Grimp are oblivious to his presence or the bags. Out of fear and confusion, Francis lowers both bags into the swimming pool. The bag opens, and like an unintended magic trick, the money floats to the surface.

Although Any Number Can Win is an entertaining film, not intended as an art cinema masterpiece or of the French New Wave, there are elements that run through the film that indicate a depth of life. Charles is a schemer but his planning comes from a deeper existential place than a simple acquisition of money.

At the beginning, we see Charles on the bus, carefully observing the conversations between workers, who’re arguing which holiday resort is most affordable, yet enjoyable. This isn’t the life for Charles, as we gather from his thoughts. He arrives in his neighborhood but the entire place is unrecognizable. Instead of houses, there are apartment buildings everywhere. Rows and rows, broken up by a feeble attempt at greenery in the midst of concrete emptiness.

Charles can’t even find his street, not only because the landscape has changed but also the names of the streets. He’s a foreigner in his own country, a displaced robber, high above the menial work of regular people. In the middle of the concrete and endless rectangular windows, Charles recognizes his house: one piece of warm and traditional architecture, sitting in the middle of apartment buildings, alone and displaced. Much like his home, Charles doesn’t belong anymore. The society is changing and not waiting for the likes of him. A new France is emerging. (We see a similar and more explicit exploration of the collision between traditionalism and modernism in Jacques Tati’s wonderful 1958 film, Mon Oncle).

However, the young ones aren’t in the best position either. Francis is rootless and it appears that he’s choosing to be that way. He’s a small-time crook who only looks for a quick return. He lacks discipline even as a thief, and is easily distracted. He’s sleazy but tough to hate because there’s something boyish and innocent about him. He’s not evil or harmful, and Delon brings out his youthful delinquency with precision. Although expressing a thief’s bravado, Delon’s Francis is not cunning or calculating. Presumably, he hasn’t grown into the role of a disciplined thief, and it appears that his encounter with Charles will not result in growth and excellence, as paradoxical as that sounds.

Delon’s image as a dark and complex man is suspended here. He brings forth Francis’ disorganized and lazy behavior, but this isn’t by any means a failure. On the contrary, it speaks to Delon’s power as an actor because he effortlessly exposes Francis’ failures as well as aspirations. What is a life of a thief? We could interpret the ending of Any Number Can Win as an exercise in comedy, but Delon’s look implies something more. Realizing that the money is lost and the heist was for nothing, he looks away in shame and agony. One wonders whether the real change was not about becoming a better thief but a better man.