The epilogue to David Graeber’s collection of essays on bureaucracy, The Utopia of Rules, is an analysis of systems at work in Christopher Nolan’s The Dark Knight Rises. Graeber, the acclaimed anthropologist whose anarchist agitations are probably best remembered for coining “the 99%” during Occupy Wall Street, went with some Occupy buddies to see the final Dark Knight film—a movie so apparently concerned with that movement—thinking they were knew what they were getting in to. Except, in his words: “None of us expected it to be bad.” He goes on to say that many things, namely “about movies, violence, police, the very nature of state power” can be understood “by trying to unravel what, exactly, made The Dark Knight Rises so bad.” In many ways, this series of essays has tried to do something similar with Nolan’s works, but instead of exploring the machinations of the world I’ve looked at that stuff which movies are made of—images, sounds, and now, at last, narratives.

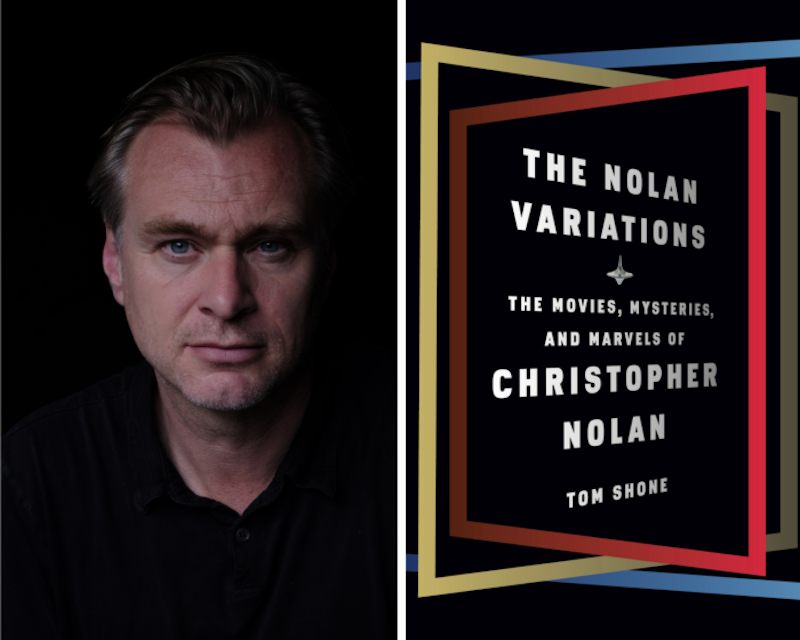

It was often rumored during Occupy that Nolan’s film shooting only a few blocks away would incorporate the movement into its narrative. While the baddies do storm and occupy a stock exchange, that image is the most exploration into the movement the film would get. The Dark Knight Rises was first worked on during the recession, and by the time the over-$200 million film was in production, there wouldn’t be time for major rewrites to properly reflect on what was happening, if that was something Nolan was even interested in. He wasn’t, and weirdly, Nolan believed his film was already equipped to comment. “It was very clear to us at the time that the sympathies of the film were very in tune with the sympathies of that movement,” Nolan tells Tom Shone in his biography on the filmmaker, The Nolan Variations, although Nolan seems a bit confused here’s about what those sympathies are, or is just delusional. Graeber points out that ham-fisted evil tactics have to be given to the mastermind villains to prevent them from being too sympathetic, with their critiques of the pompous rich being so similar to that mass movement of the early-2010s.

Nolan’s proclivity is to always come back to the singular hero, the one above the rest, looking down on the city: “Bruce literally has to lose everything and become bankrupt before he can triumph.” He thinks there’s something inherently populist in his vigilante moonlighting billionaire, and having him stripped of his financial securities makes him at one with the people, instead of still holding his patronizing, patriarchal position over them. Moreover, the anarchic revolution of The Dark Knight Rises doesn’t resemble Occupy for the simple reason that it’s a carefully orchestrated event led by a shadowy conglomerate seeking to destroy the world out of some misguided moral righteousness, as opposed to an organic reaction against financial mismanagement and misanthropic corruption from the cores of capital. In this sense The Dark Knight Rises couldn’t have anything to say about Occupy or the state of the world, because it’s not about that except in images. When Nolan screened Gillo Pontecorvo’s militant classic The Battle of Algiers for the crew of Rises, he wasn’t doing so for the reasons that countless left-wing radicals have studied the movie, but for its cinematography.

The contradiction with Nolan is he simultaneously believes that his films exist outside of politics while being reflective of political positions. About the Dark Knight films he says they “are not political acts. They’re exploring ideas of fears that are important to all of us, whether on the Left or the Right.” And yet he says, “The Dark Knight is about anarchy, and The Dark Knight Rises is about demagoguery. It’s about the upending of society.” Perhaps he believes that his firm belief in upholding the status quo, the ultimate goal of Batman, isn’t a political act when represented on film—he thinks he’s not doing anything because the result isn’t change, but stasis. It makes one wonder if Nolan would think Giuseppe Tomassi di Lampedusa’s novel The Leopard isn’t a political act, with its exploration of Risorgimento Italy summarized by the famous line: “If we want things to stay as they are, things will have to change.” Although that might be an apples and oranges comparison, because Lampedusa’s novel explores where Nolan’s works presents.

Nolan pointed out in his biography how odd it was that critics and journalists didn’t make the connection between his own father dying during the making of Inception, and the corporate succession at the heart of the film’s dream heist involving a son taking over his passing father’s business empire. Ostensibly this is a strange void in the contemporary criticism; why wouldn’t they be drawing clear links between the filmmaker’s life and the narrative of the film itself? The simple answer that Nolan may be missing is that, while it’s clearly on his mind, his film is in no way an exploration of this grief, but only uses it as a representational McGuffin within his structural narrative. The real, existing context of the narrative bits are only important insofar as they’re the stuff with which the movement is made of, not for any symbolic meaning that could be gleaned underneath. In fact, it makes any symbolic meaning embedded into his films all the more opaque and nonsensical, even when they’re supposedly being direct. It’s not out of line with the trends of today—in a world of “elevated horror,” genre cinema is more concerned with aggressively presenting ideas like “grief” rather than having their conventions engender thematic exploration under the mask of entertainment, as they always have. Perhaps the focus on his unique narrative machination has distracted him from the often undervalued structures of genre.

One of the most striking narrative images in all of Nolan’s films seems ripped right from the bitter, sentimental hands of John Ford. In the stirring conclusion to The Dark Knight, Batman (Christian Bale) confides he’ll take the blame for the murders committed by the good-boy public servant turned two-faced villain, Harvey Dent, in order to give people a myth to believe in. This launches a montage of Batman running from the police, Commissioner Gordon (Gary Oldman) destroying the Bat Symbol, and giving a speech about what a great man Harvey Dent was in front of his towering portrait. That last image is inescapably similar to the masterpiece of Ford’s Cavalry Trilogy, Fort Apache. After the harsh, haute Col. Thursday (Henry Fonda) has led his men into a foolish, Custer-like last stand, Capt. Kirby York (John Wayne) is recounting the incident. Although Kirby and his rugged, western ways have been diametrically opposed to Thursday’s East Coast regimentation, seeing Thursday refuse to leave his men during the doomed attack creates a new ambivalence in Kirby, one which leads him to building the myth that Thursday was a great leader, one that keeps the spirits of the men alive by maintaining the tradition of the cavalry. It’s a complicated, conflicting ending that reveals the way we hide the truth from ourselves to make causes mean something. The ending of The Dark Knight instead tells its audience who the heroes and villains are and always were, it reaffirms the images already built and shows that the people who live outside our privileged knowledge as being ignorant and incapable of handling the truth. The images that the characters always seemed to be always were, although the structural sleight-of-hand makes the audience think something may have changed or remotely complicated those perfect pictures.

What makes those perfect pictures, those monumental representations of ideals so odd in Nolan’s movies is their placement within those texturally real worlds. His characters are anything but real, yet he chooses to film them as if they were. It’s an aesthetic predicament that goes unexplored, and serves to obfuscate to audiences what he’s really doing. Graeber’s most poignant observation about Nolan’s films is that they seem ostensibly to be political narratives, with their real-world setting and supposedly topical attentions, yet that’s only a masquerade for their psychological dramas. Nolan’s Dark Knight trilogy is solipsistic—nothing exists outside of that which is relevant to the mind of its hero. The whole world exists within a psychological box, whether a post-modern, post-industrial Batcave or a city walled off from the rest of the world, it’s like a stage suspended in a black void in a Brothers Quay film.

Arguably the best of Nolan’s films is the one where the narrative and character work had already been done for him; all he had to do is create the physical context for which the film could take place and present it in his developing elliptical style. The Prestige, based on the 1995 novel by Christopher Priest, is a story about two feuding magicians in the science-fiction like past of early electricity in the late-19th century. It’s the perfect Nolan narrative, moving as the two rivals, Alfred Borden (Christian Bale) and Robert Angier (Hugh Jackman), read each other’s diaries, always finding themselves on the back foot of the other’s sleight-of-hand. Here the narrative trickery that drives the excitement of Memento and the child-like wonder of seeing something seemingly impossible like in Inception, Interstellar, and Tenet is combined with very real, defined, and complex individuals fighting through their personal and professional lives to pursue their passions. It’s also a stunningly efficient film, using Nolan’s penchant for directly presentable images to move fast. Combine this with the room he gives the actors to inhabit their performances—it’s Nolan at his most Malick-like. But Nolan being Nolan, a fully realized mind, one torn between two halves can never be just that, and it’s almost a joke that one of the most interesting and complex characters he ever put on screen is revealed in the final twist to be two people living one life.

The Prestige shares a thread that weaves through all of Nolan’s narratives that is little commented on—faith. So much of The Prestige is spent confronting belief, whether in tricks or in science, the same way characters express their faith in human justice in the Dark Knight films or their faith in the scientific order of the universe in Interstellar, where a riff on Murphy’s law says that anything that can happen, will happen. No film is more exemplary of this than Tenet, where entropy can be reversed and time move backwards, only for the world to stay the same. “What’s happened happened, which is an expression of faith in the mechanics of the world. It’s not an excuse to do nothing,” Neil (Robert Pattinson) tells the Protagonist (John David Washington) near the end of the film. When the Protagonist questions that idea of faith, Neil tells him it’s just another word for reality. Everything will stay the same, nothing will change because nothing can change, whether that’s forwards or back in time. It’s a narrative mobius strip, a theme that reifies itself. It’s a long-winded way of making Nolan’s films seem like they’re saying something, while saying nothing at all. There really isn’t much to glean, because there’s not much out behind it. In fact, it challenges Andrei Tarkovsky’s notion that if an image is meaningful to the maker, something of that meaning will be transposed to the audience. Nolan seems to think he was commenting on his father’s death in Inception but all there is is the image of it, like how the only connection any of Nolan’s films have to his outcast brother is that they posit that the past can’t be changed—nothing more, nothing less. All that’s left here is some weird void where meaning seems like it should be hiding, but isn’t. It’s lifting a tray cover to reveal nothing on the plate, all that it has was the anticipation of something behind the curtain.