After For Your Eyes Only, released in 1981, Roger Moore thought he was too old to play James Bond. Producer Albert R. Broccoli agreed and conducted screen tests for a new 007. Various reports had him ready to hire Oliver Tobias or James Brolin for the next Bond film, Octopussy. Then Kevin McClory spoke up.

McClory owned the rights to the story of Thunderball, and announced he’d be filming a remake starring Sean Connery as James Bond. His movie would come out in late-1983, just a few months after Octopussy. Broccoli had no desire to pit a new Bond against Connery. So Moore, who’d be 55 when Octopussy opened, reluctantly agreed to return. His age is a problem. But it’s not the only one, or even the main one.

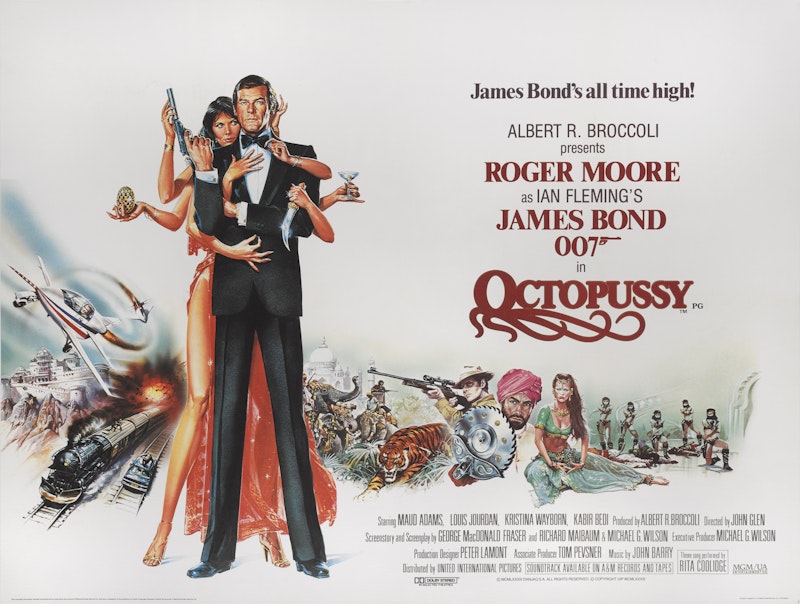

At least Octopussy starts with a strong pre-title sequence, often the case for Moore’s Bond movies. You get what you expect from a Bond film: action, fast cars, attractive women, and surprising gadgets—in this case, a mini-jet. Then the plot kicks in. MI6 agent 009 is murdered in East Berlin, his death linked to the curious appearance at auction of several Fabergé eggs. Bond investigates, and travels to India where after assorted skullduggery he encounters a woman calling herself Octopussy (Maud Adams) who leads a cult of beautiful women on a private island. One of her associates is working with a Russian general (Steven Berkoff) who plans a convoluted false-flag operation to trigger a nuclear explosion in Berlin. The general expects the explosion will lead European peaceniks to force the American military off the continent, after which Western Europe will be easy prey for the Red Army.

The movie takes its title from Ian Fleming’s short story “Octopussy,” and the business with the Fabergé eggs from another story, “The Property of a Lady.” The actual plot of “Octopussy” (the story) becomes part of the background of Octopussy (the character), summarized in a monologue. A bit of the novel Moonraker makes it into the movie, too, but this is less an adaptation than a new adventure with a borrowed title.

George MacDonald Fraser, writer of the Flashman books, did an early draft of the script; the combination of Fraser and Bond seems natural, but he was rewritten by veteran Bond scripters Michael G. Wilson and Richard Maibaum. By this time, after more than 20 years of Broccoli’s Bond movies, there’s a family-firm aspect to the productions. The films are made by many of the same people—returning for this movie from Eyes Only are Broccoli, Wilson (Broccoli’s stepson), Maibaum, director John Glen, cinematographer Alan Hume, and production designer Peter Lamont. Maurice Binder contributes a title sequence, for the 10th consecutive Bond production, and this is the 10th Bond film to have music by John Barry.

These are experienced professionals who know the franchise, the material, and how to work with each other. But the absence of new blood leaves the franchise in a rut. John Glen’s direction on Eyes Only was nothing spectacular, and again here there’s a pervading banality, a lack of spectacle and panache. (Broccoli’s production choices are becoming obtrusive, as in casting his acquaintance Vijay Amritraj, a professional tennis player, as Bond’s Indian ally.)

The storyline has a larger scale than Eyes Only, but like that movie it’s a straight-ahead Cold War tale. But it’s not credible, hinging on peace activists having more influence than seems likely. More to the point, there’s an inconsistency of tone between the overall plot and the gimmicks within. Bondian paraphernalia, like obscure cults of women warriors or a circus of spies, need a sense of the bizarre and outré to work. You can’t shoehorn those into a standard-issue spy story set in something like the real world.

The Bond films of the 1960s, and some from the 70s, understood this. They knew how to go big without going entirely camp. Glen never figures that out, and so here we get a story with interesting ideas that refuses to allow itself to have fun. The visual potential of Octopussy’s luxurious island, or of Bond undercover in clown make-up, never comes to anything.

Instead, Glen incorporates camp into his Bond films through bad jokes when the action ramps up, as though uncomfortable with the set-pieces that bring viewers to a Bond film. A hunting sequence in India with Bond as the quarry is a good idea for an action scene, but undermined by jarring gags: Bond commanding a tiger to sit, Bond letting loose with a Tarzan yell. Again, the movie falls into a tonal mishmash, and so for all the varied settings in the movie, nothing sticks.

The film deteriorates as it goes on. By the time it gets to the tacked-on cheap-looking set-bound final battle, it runs the risk of giving audiences time to think. At which point they might ask questions like: should we be cheering for the British Empire maintaining a secret base in India? Is it cool that an Afghan prince is played by a Frenchman? Isn’t the whole idea of Bond running into a secret cult in India a bit Orientalist, even (or especially) if most of the cultists are played by white women?

These things aren’t what the movie wants you to focus on, but it doesn’t give you anything to distract from them. The film’s perfunctory, an entry in the Bond canon made by the same old hands just because the schedule called for it. The scene with Bond dressed as a clown comes off as a message from the filmmakers’ subconscious. Octopussy did its job, and made money. But it did nothing to quell interest in Connery’s upcoming rival Bond.