In his new memoir, Every Man for Himself and God Against All, Werner Herzog writes, “To this day, I can learn only from bad films. The good ones I watch in the spirit in which I watched when I was a kid. The great ones, even when I see them many times, are just an enigma.” In the first week of 2024, I rewatched Dazed and Confused and Fast Times at Ridgemont High; the latter I last saw a year and a half ago, but it had been at least 20 years since I’d seen Dazed and Confused, Richard Linklater’s 1993 teen memory masterpiece. Linklater and Amy Heckerling’s films are beloved and successful for slightly different reasons, and while they’re both high school movies, the most important thing they have in common is their structure.

Neither of these films have a story. There are events: Jennifer Jason Leigh gets an abortion, Jason London refuses to sign the loyalty pledge for his football team, but neither of these plot points are what people remember from Fast Times at Ridgemont High or Dazed and Confused. They remember moments: one girl helping another pull up the zipper on her jeans with pliers, Wiley Wiggins getting paddled in slow motion by Ben Affleck, all of the kids in Mr. Hand’s class smelling their freshly mimeographed papers, and of course Phoebe Cates getting out of the pool. These are perfect movies, a designation that can only be given when it’s felt; it can’t be explained or elaborated—they remain, as Herzog writes, “an enigma.”

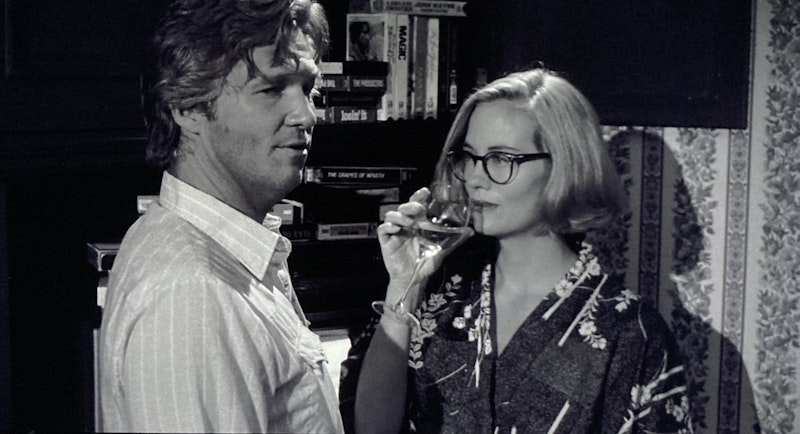

Peter Bogdanovich’s The Last Picture Show is one such film. It’s an enigma, a film without a story that has more feeling and depth in it than anything else Bogdanovich ever directed. It goes beyond author Larry McMurtry’s work as well, reaching past something as earthbound as his novels and into the spiritual and enigmatic. Unlike the above films, there are some clear elements that make The Last Picture Show as great as it is: black and white photography and no proper score. All of the music is old country songs, mostly Hank Williams, played diegetically through radios and televisions.

Bogdanovich adopted the same two strategies in his 1990 sequel Texasville. Only 19 years had passed between Texasville and The Last Picture Show, but their internal timeline is a bit longer and backed up: 1952 to 1984. Before the Criterion Collection’s recent re-release of The Last Picture Show with Texasville, I’d never seen the latter, always dismissed as another unnecessary sequel to a classic 1970s movie that came way too late, just like two others from 1990: The Godfather Part III and The Two Jakes; but I love The Last Picture Show so much, how bad could it be in intended black and white form, at Bogdanovich’s intended length of 150 minutes?

I kept thinking of what Herzog wrote. With most of the people from The Last Picture Show, save Ellen Burstyn, and the same writer and director, everything lacking in this sequel comes into sharp relief. Bogdanovich’s screenplay, adapted from McMurtry’s novel, is full of snappy Hawksian dialogue that’s all so obviously written, unlike the sublime and simple words of the first film, of which there are few (Texasville is a much more verbose film). This story shifts its focus from Timothy Bottoms’ Sonny to Jeff Bridges’ Duane, a much less interesting character by a much less interesting actor. Bridges has more range than Bottoms, but he’s never approached the latter’s work in The Last Picture Show, and his phoning in is even more obvious in Texasville when Bottoms is better than ever.

Sonny suffering from early onset dementia and “seeing movies in the sky” is poetic and of a piece with the first film, but Texasville is just another mid-life crisis movie about Baby Boomers cheating on their wives. The first movie is closer to Antonioni than The Big Chill or the work of James L. Brooks. Cinematographer Nicholas von Sternberg also reuses the same slow-dolly-into-a-medium-shot throughout Texasville’s 150 minutes, an elegant camera move used sparingly in The Last Picture Show, most notably in Ben Johnson’s speech at the lake. Here, it’s no mystery.

But there’s no doubt this film benefits from being seen in black and white: it’s as much of a special effect as anamorphic widescreen or Technicolor. The black and white is endemic to both stories, where people are living already dead in a small Texas town. Both films slowly fade in and out of a roaring, empty sky, and it is only in these bookends does Texasville even suggest the greatness of The Last Picture Show.

—Follow Nicky Otis Smith on Twitter: @nickyotissmith