When I first considered writing about The Good War and Those Who Refused to Fight In It, a 2000 PBS documentary recently released on DVD, the U.S. was only involved in two wars. In the time between pitching the idea and receiving the documentary, the U.S. picked up a third. So now we’re fighting in Afghanistan, Iraq and Libya. Possibly by the time this is published, we’ll have taken on a fourth. President Obama hasn’t shown much desire to invade Iran, but maybe he’ll get a sudden inspiration. Who can tell?

“The Good War” of the DVD title refers, of course, to World War II. But it could refer to Libya too, or either Iraq war, or the Civil War or World War I. All wars are good wars. Who would fight in them if they were bad?

Oddly, given the title, the question of good wars and bad wars doesn’t really come up much in this documentary. A couple of conscientious objectors do note that, given Hitler and Pearl Harbor, WW II was an extremely difficult war to opt out of. One says that, when asked what should be done about Hitler, he had no response. Another suggests that the U.S. was not willing to try the program of peace—but the interviewer doesn’t ask what exactly that program might have been, and so it remains a mystery.

Instead the documentary mostly focuses less on sweeping ethical dilemmas, and more on the individual histories of the COs. The result is a typical PBS experience. Lots of people are interviewed in front of bookshelves. Lots of period footage rolls by as obtrusive music tells you how to feel about, for example, the insane asylums where many COs worked. Lots of earnest narration is delivered in a voice similar to Ed Asner’s (narration provided, in this case, by Asner himself.)

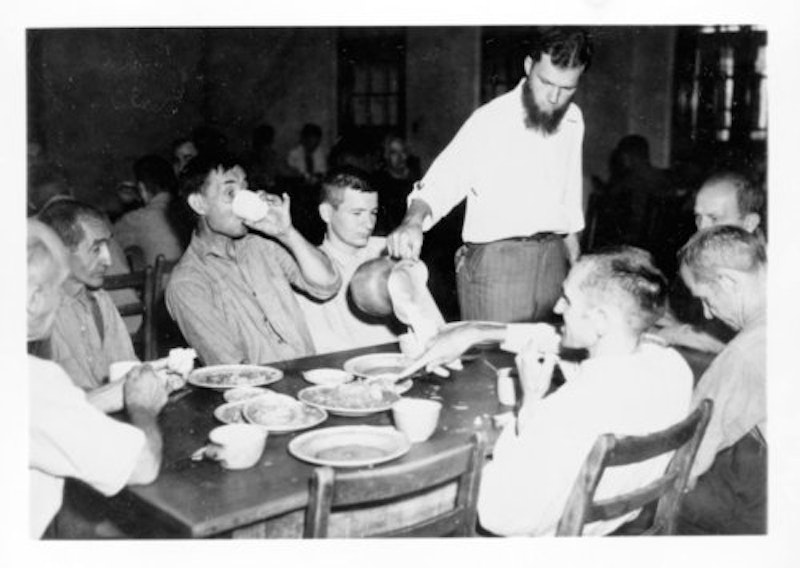

There’s nothing especially wrong with any of that. For those already familiar with the story of COs in WWII, I’d imagine that this would offer little new—but for people, like me, who haven’t studied the period, there’s plenty of interesting detail. Perhaps the most intriguing section, for me, was the discussion of how many COs volunteered for medical experimentation. Stung by charges of cowardice, a number of COs allowed themselves to be starved nearly to death or injected with hepatitis and typhus. Some died. The documentary doesn’t mention what, if any, useful knowledge was gained from these endeavors. I presume if life-saving drugs had been developed, they would have told us. It seems likely, therefore, that these men, out of a mixture of personal pride and societal pressure, sacrificed their health and risked their lives for nothing but the career advancement of bureaucrats. They might as well have been in the army. Except, of course that they didn’t have to kill anyone.

It’s nice to see evidence that pacifists can be as foolishly macho as anyone, though you have to tease that insight out from the general tone of benevolent hagiography. Admittedly, if you’re going to idolize someone, these folks seem like a decent bunch. Bill Sutherland, longtime advocate for African-American rights and a committed pacifist, talks with admirable equanimity about how his four years in prison was not an interruption of his activism, but an extension of it—he spent his time inside fighting prison segregation. Sam Yoder, a Mennonite CO, comments with rueful humor that when he returned home after the war, “no band was there to welcome me back,” and then proudly announces that his own two sons have obtained CO status.

What’s mostly missing from these tales of individual heroism, though, is a sense of how they connect to a wider picture of war, peace, and community. The logic of war isn’t built on individual heroics. That is, people see service in war as heroic, but war isn’t usually justified on the basis of that heroism. It’s justified on the basis of its effectiveness. You defeat the German hordes by bombing them. You defeat the evil Libyans (in aid of the good Libyans) by bombing the first (and, ideally, not the second.) Heroism is nice, and will be celebrated, but it’s not exactly the point.

There’s no similarly utilitarian argument voiced here on behalf of pacifism—at least not with any consistency. Instead, everyone agrees you should stay true to your conscience. In one of many mini-bonus-documentaries included on the disc, for example, Daniel Ellsberg argues that he was truer to himself and his patriotism when he released the Pentagon Papers than when he enlisted. And he’s both moving and convincing when he says it. But, what if your conscience tells you to go off and kill Japs? What if your conscience tells you to bomb Libya in order to prevent genocide? Does that mean that some people are right to shoot each other and others are wrong? Are there different ethics for different people depending on what conscience God happened to hand them?

It’s clear that many of the people here don’t believe that. Kevin Bederman, an Iraq war CO interviewed for another mini-doc, characterizes war (in an engaging Southern drawl) as “the most base thing human beings can do to each other.” Other COs note the importance of love. Some reference Gandhi’s ethic of peace.

What the documentary never does, though, is actually castigate people who fight. There is no denunciation of warmakers. And without that denunciation, it’s difficult to see the ethical choice for peace as the only ethical choice. The COs are right, but the warmakers aren’t wrong.

I’m sure that this is not the attitude of many of the people interviewed here. George Houser, for example, publicly refused to register for the draft in order to protest the possible U.S. entry into World War II. That was undoubtedly based on his feeling that preparations for war were wrong. But the documentary dwells on his heroism at the expense of the critique—not quite realizing that without the critique, the heroism loses its point.

Theologian Stanley Hauerwas, in his book Dispatches from the Front, argues that for Christians, non-violence is not an ethic or a theory, but a way of life which is “unintelligible apart from theological and ecclesiological presumptions.” Pacifism doesn’t arise from an inward-turning confrontation with conscience; it comes out of a particular kind of communal faith. He adds, in reference to the first Gulf War:

Surely, the saddest aspect of the war for Christians should have been its celebration as a victory and of those who fought it as heroes. No doubt many fought bravely and even heroically, but the orgy of crusading patriotism that this war unleashed surely should have been resisted by Christians. The flags and yellow ribbons on churches are testimony to how little Christians in America realize that our loyalty to God is incompatible with those who would war in the name of an abstract justice. Christians should have recognized that such “justice” is but another form of idolatry to just the degree it asked us to kill. I pray that God will judge us accordingly.

Hauerwas, in short, is able to do exactly what the documentary will not: he is willing to say that if the path of nonviolence is right, and those who follow it are heroes, then the path of violence is wrong, and those who follow it are at the least, not heroes. His non-violence is not about his personal conscience and what’s right for him. It’s about what’s right for him, and for his community, and for his God, and by extension, for his nation and the world.

Though the documentary has a lot of practical advice on avoiding the draft and obtaining CO status, it’s all offered very much for those who might want it; there’s little in the way of evangelical fervor. Nobody here says, damn it! You—yes you, watching this! It’s your moral duty to become a CO! Which is a shame because, inspiring as many of these personal stories are, if we’re ever going to get to a place where we’re waging, say less than two wars at a time, I think we’re going to need a pacifism with a bit more fight to it.