It’s often said that society functions based on the way a pendulum swings but isn’t this simplistic? Aren’t people and the experience of time more nuanced than such a bifurcated way of looking at life? The conflict and tension are most palpable in a society when there’s an interplay between creation and destruction, Eros and Thanatos. In the midst of chaos, love is often forgotten, or at least, the authentic meaning of love.

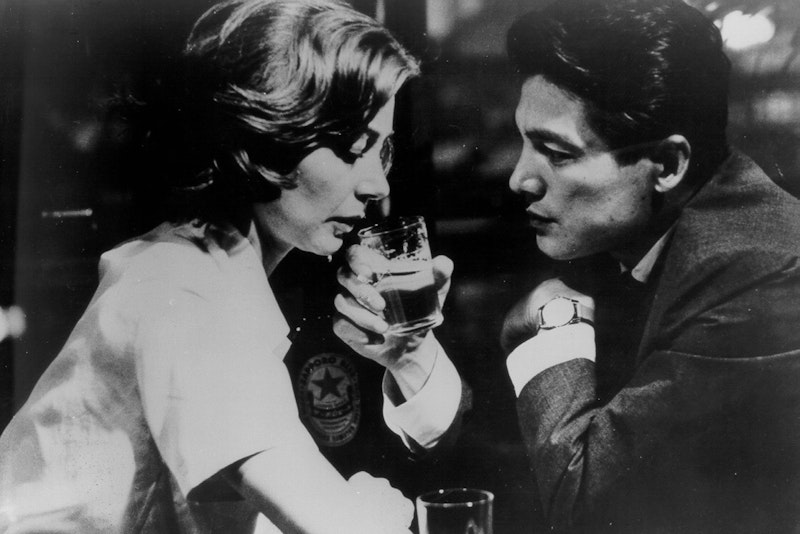

Alain Resnais’ classic film Hiroshima mon amour (1959) is one of the most beautiful examples of love in a time of destruction. The script was written by the incomparable French writer, Marguerite Duras, and it deals with two people—a Japanese man (Eiji Oakada) and a French woman (Emmanuelle Riva)—who consummate a passionate but brief love affair in Hiroshima years after the atomic bomb attack. Duras created characters who remain nameless archetypes of masculinity and femininity, and this is one of the reasons why she remains a writer who has captured the elusiveness of the erotic experience in a mystical and physical way.

The film unravels in a non-linear way. Its opening is a symbolic gesture of the themes that will develop: two bodies—that of the man and the woman—are intertwined in an erotic embrace. As the bodies move, it becomes unclear who’s female and who’s male, which adds to the anonymity and privacy of the erotic experience. Their nude bodies are covered in dust, which appears to be golden but it is really the dust of the exploding bomb—a reminder of the evil and darkness that took place.

For most of the film, we hear a narration that gently comes from both the man and the woman, as they present their own versions and perceptions of the love affair. “You saw nothing in Hiroshima. Nothing,” says the man. “I saw everything. Everything,” says the woman. They contradict each other right from the beginning, as if to say they’re living in alternate worlds, which can’t be mutually understood or reconciled. She, a French woman, and he, a Japanese man, can’t possibly have anything in common, culturally or otherwise. The respective nations have nothing to say to each other, if we assume that these two lovers are merely representatives of their countries.

This is the beauty and mysticism of Duras’ literary influence. In her writing, love, sex, and eros aren’t bound by geographies. Rather, Duras creates human corporeal landscapes that participate in each other’s creation and destruction. The notion of the feminine and masculine is important for Duras because it’s the foundation of not only the erotic difference between men and women but also of how a whole or fragmented human being emerges from this difference. For Duras, the pinnacle of human existence is in an encounter.

But this isn’t an ordinary encounter. It’s an event that moves beyond time. The lovers in Resnais’ film are existing outside the boundaries of chronological and political time. Whatever unification between human beings is impossible politically or culturally, for Duras and Resnais, it’s certainly possible erotically. This is one of the reasons why Resnais shows images of the attack on Hiroshima. The dead, the wounded, the crying children, the confused victims, the complete devastation and destruction wakes us up from the slumber. We’re forced to see the face of the other person who’s been dehumanized and pushed into the realm of complete annihilation. This is the public world of ethics: inescapable and dominant.

Such a world recedes into a memory that wants to be forgotten, and the same symbolic means are employed in the film as well. Resnais focuses on the faces of the man and the woman, their connected bodies, as well as the privacy and intimacy of an erotic connection. The world that’s in the bedroom is the world that forgets the war, the dead, the wounded, and the suffering.

The woman tries to make sense of it all. The man reminds her of a previous lover whom she has tried to forget. “Like you, I wanted an inconsolable memory,” she says. “A memory of shadow and stone. Each day, I fought, all alone, with all my might against the terror of no longer knowing the reason to remember… Why deny the obvious necessity of memory?”

On one hand, we have the memory of Hiroshima and the importance of remembering the past deeds, presumably so they wouldn’t be repeated. But man is fallible and is bound to falter again and again. “Listen to me. I know this, too,” says the woman. “It will happen again. 200,000 dead, 80,000 wounded in nine seconds. Those are the official figures. It will happen again. It will be 10,000 degrees on the earth. ‘Ten thousand suns,’ they will say. The asphalt will burn. A deep chaos will prevail. A whole city will be raised and once more crumble into ashes.”

This form of collective and public memory is a burden that’s easier to carry than the burden of an individual memory. It’s in this personal and private memory that matters of the heart become visible. We assume that great freedom comes from seeing one’s face in the mirror but what if more knowledge about the destructive illusions brings more sorrow and a self-imposed prison?

The experience of the lovers comes to an end, yet even that’s ambiguous. What kind of end? The man speaks: “Some years from now, when I have forgotten you and other romances like this one have recurred through sheer habit, I will remember you as a symbol of forgetfulness. This affair will remind me how horrible forgetting is.” In many ways, memory is fragile. Sometime, we willfully forget something and over time, the memory we once knew becomes something else entirely. We impose on our fragmented existence the force of the present and the anxiety of the future. The past is either ignored or changed to suit the ennui and restlessness.

It seems silly to juxtapose destruction and war with two strangers in the midst of a love affair. Yet this isn’t an indulgent endeavor of Resnais and Duras. Rather, Hiroshima mon amour is an artistic gesture that points toward the humanization of love. Today, we lack embodiment of the people and things that surround us, effectively re-making others and ourselves into cogs and germ carriers, who relate to the world in an unnatural way driven by the virtual and illusory matrix of relationships. Despite this, the reality of creation and destruction remains. If an erotic encounter between the man and the woman ceases to be deemed important, then how can we expect to think beyond the political time, in which people are turned into categories created only for the perpetuation of ideology? Without eros, there’s no life, only changing forms of destruction, violence, and ideology.