It always struck me as strange that the quintessential New Year’s song—”Auld Lang Syne”—is what closes out the quintessential Christmas film, It’s a Wonderful Life. Thematically it makes sense: a celebration of friendships new and old, a threshold song of what's connected people and the relationships on their forward-feet. Capra’s film and the Robert Burns take on a Scottish folk song share a sentimentality. Capra’s film is one of people coming together, meant to be watched together, much as “Auld Lang Syne” is a song reminiscing on the old times and meant to be sung in celebratory harmony. Capra’s classic is, to me, a Christmas Eve event—I’d rather spend the day with John Ford.

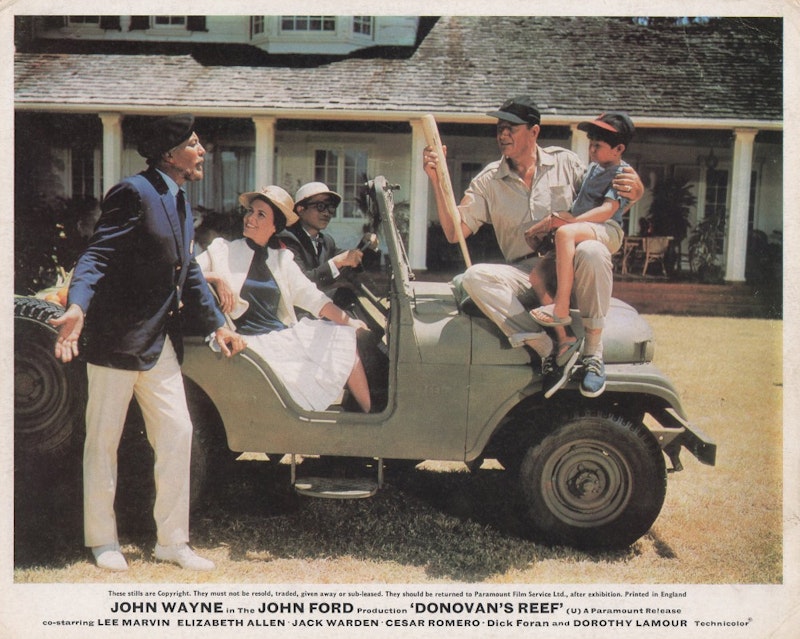

The two obvious choices for a “Fordsmas.” First there’s 3 Godfathers (1948), a Harry Carey Jr. vehicle based on a novelette and adapted by Ford once before in 1919 as the (lost) Harry Carey-starring Marked Men, wherein three outlaws stumbled upon a dying woman who’s just given birth on Christmas and they adopt her baby while on the run, noting their parallels to the Biblical Magi. But Ford’s best take on the Three Wise Men comes during the Christmas mass in Donovan’s Reef (1963), where they’re presented as the King of Polynesia, the Emperor of China, and King of the United States of America to stand in for the multi-cultural, utopian (in a Ford way) melting pot of the postwar South Pacific.

Ford’s best Christmas film is a quiet one, where a lonely old man is set to spend it by himself when the young men he fosters comes trickling in. The man’s Marty Maher (Tyrone Power), an Irish immigrant who landed at West Point as a server in the academy’s grandiose mess hall and worked his way up to become an esteemed athletic instructor. Marty’s life becomes the academy, at first learning its strange rituals, then meeting his eventual wife Mary (Maureen O’Hara), thinking of going back to the old country, and then ultimately realizing his bones will always be at West Point. When Marty and Mary’s first child dies only hours after birth, she has to relay to Marty that the doctor told her that she won’t be able to have another—the cadets will start to stand in as their children. After Mary died sometime later, Marty’s alone in an institution that seems aged in its traditions compared to the changing world. Yet there’s still old Marty Maher sitting around with the cadets on Christmas, telling stories of the old football teams, keeping the institution alive through personal perspective rather than just the outright rules and systems that ostensibly define the academy to the outside observer.

When Marty’s set to retire, he gets called onto the parade ground where a full-dress display is in order. The band’s playing an old Irish folk tune, and Marty’s surprised—the superintendent tells him the cadets put on this parade, to remember their old friend. Marty can see the ghosts of his life over the horizon—his wife Mary, his father—as the military band plays “Auld Lang Syne.” In Ford’s hands, the tune is more a dirge than a revelry, one where people are able to live on even though they’re dead, because others are keeping the flame burning.

Ford and Capra differ greatly here. Capra, the first-generation Italian-American, finds his catharsis in the affirmation of community beyond a personal Christian doubt towards one’s own importance. Capra’s interested in the building of America. Ford, the second-generation Irish-American, is elegiac in his remembrance of what’s constantly lost, and finds his vitality in trying to pass the bones along to keep them alive. Ford’s interested not in the revelation of foundations, but the acceptance that a community is built on flimsy architecture, and it takes work (often through tradition, ritual) to keep them alive. Capra sees “Auld Lang Syne” as a friendly cheers, Ford sees it as a “Lest we forget.”