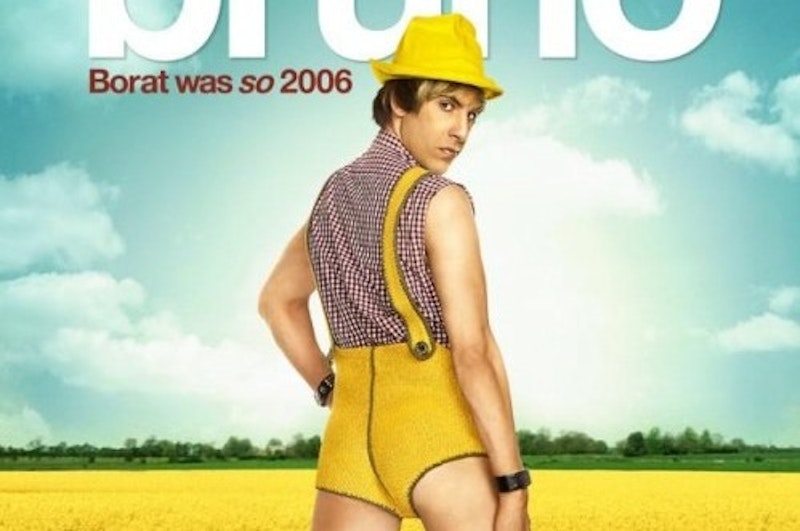

Lost amid the predictable “Is Brüno Good For the Gays?” hoopla leading up to Sacha Baron Cohen’s newest film was a more pressing and germane issue: Is Brüno Good For The Movies?

The question of Cohen’s political value is predictable because our current cultural dialogue politicizes everything in the blandest way possible, reducing all pop products to blunt weaponry in the culture wars. But it distracts from the larger issue, which is whether we’re content to have bad art shoved down our throats. I don’t mean bad as in “poorly made” or “unbelievably unfunny,” though Brüno is both of those things; I mean bad as in mean-spirited, dialogue-deflating, morally suspect. By politicizing every mass-marketed piece of studio effluvia, by asking whether or not something like Brüno will help one side or the other, we prevent ourselves from realizing that crap like Brüno isn’t actually worth our time in the first place.

Were we to judge Brüno by the right criteria—that is, as a film—we might come to such a conclusion. Cohen’s movie is smug, narratively incoherent, and almost bizarrely devoid of humor. It is also nearly identical—in tone, structure, sensibility, and setting—to Cohen’s earlier Borat, which was lavished with a 97 percent Fresh rating by Rotten Tomatoes’ top critics. This has led to a very enjoyable game wherein critics who loved Borat for its supposed “satire” now have to backpedal as they see Cohen’s unfairness revealed under the light of subpar material. Thus The Wall Street Journal’s Joe Morgenstern, who gushed in 2006 that Borat was “a world traveler who can help replenish the New World's dwindling supply of irreverence,” now turns up his nose at Cohen’s methods, though they’ve scarcely changed: “Brüno, bent on nothing more or less than becoming famous, is only a provocateur, and so relentless in his provocations—you really don’t want to know the extent of his anality or frontal nudity—that his scandalous conduct grows tedious and unpleasant.” Michael Phillips of The Chicago Tribune agrees, having claimed that “Borat has a way of bringing out the latent prejudice in many of his on-camera interviewees” but that “[t]he problem with Brüno comes in mistaking blatancy for comic gold.”

I agree that Borat is much funnier than Brüno, but the deftest parts were the situational gags Cohen came up with, like the protagonist leaving his village in a horse-drawn sedan, or his partner drinking water mere feet downstream from Borat’s urine trail. Every time Cohen tried to pull his customary bait-and-switch, his film fell flat, as when he delivers a bag of his own feces to a southern woman’s dinner table and she politely informs him what to do with it. Cohen purported—and critics fell over themselves in agreement—that Borat somehow reveals the latent bigotry and close-mindedness in American society, but this seems false, and not only because every country boasts the same qualities in its more conservative subcultures. But for every drunk fratboy/redneck moment of intolerance that Cohen "reveals," he shows another moment of unbelievable understanding and tolerance on behalf of his victims, such as the bemused acceptance by straight-laced American men of Borat’s cheek kisses, or a hostess’s insistence that, with a little learning, he could assimilate nicely into American culture.

In Brüno, the non-Candid Camera humor is cruder—limited mainly to jokes about the protagonist’s “cockaholism”—and the faux-journalistic scenes are even cheaper. In both cases, Cohen’s minor satiric victories are totally hollow. He graphically simulates fellatio in front of an unsuspecting psychic, and can’t even get a rise out of the guy: “Okay, good luck in life,” is all the man says once Brüno finishes. One scene where Cohen does successfully antagonize his audience occurs when he brings his fake-adopted African baby to a daytime talk show with an entirely black studio audience. But it takes such incredible effort for Cohen to irk these people that there’s no point to his stunt; who wouldn’t disapprove of a visibly juvenile idiot claiming to have gotten an African baby by trading away an iPod, naming it O.J., and blithely flaunting his lack of parenting ability. If Cohen is satirizing celebrity adoption, why is his target a group of civilian African Americans? If he’s satirizing black American homophobia, what good does it do to make his antagonist the most obnoxious fag-on-steroids imaginable?

I can almost sympathize with Cohen, however—he’s just following the money. We get the demonizing blather of Brüno because we lined up by the millions to not only see Borat, but to praise it as societally useful. I imagine Cohen feels as shanghaied as his boobish subjects, now that his once-lauded style is suddenly (relative to the success of Borat) being critically disapproved of and falling flat at the box office. He might also be looking at The Hangover—a staggeringly uncreative and routinely cruel movie that nevertheless grossed $200 million in a few weeks earlier this summer—and wondering why there’s a small backlash afoot with regard to his newest parade of buffoonery. The Hangover leaves no easy joke unmade and no easy target unmocked. Black and Asian stereotypes, baby endangerment, homophobia, wanton profanity, and male fear of weddings are all played for yuks, and all varieties of women—strippers, uptight shrews, nice girls who want to get married—are shown in caricature. This doesn’t offend me; it just bores me. But The Hangover brings in Will Smith money nevertheless, and its sub-Apatow, frat-ready humor somehow gets good critics to label it “psychologically true” and akin to “the equivalent of postmodern alchemy.”

You can’t laud Borat and The Hangover and then object to Brüno on moral grounds. More generally, you can’t praise our current vogue of slovenly-male-doofus comedy and then object when studios respond to that demand by getting more crass and meaner each summer. Some of the best comedies ever made have been almost sadistic to their characters, from Chaplin to the Ealing masterpieces like Kind Hearts and Coronets to Kubrick’s great pair, Lolita and Dr. Strangelove, to the best of the Coen Brothers’ comedies. (One of the funniest moments in Burn After Reading is the suspenseful reveal of a character’s ornate sex toy; very nearly the same prop is used in Brüno, but only to show how much the title character likes getting schtupped, not to upend our narrative expectations or expose a person’s hidden depravity.) But there’s no cleverness in the cruelty of Brüno, just as, contrary to critical judgment, there’s no real insight underneath The Hangover’s crassness. Both merely aim for the easiest of audience reactions: “I can’t believe he did that!” And who is that good for?

Lean and Mean

Why are we content to watch comedies as bad as Brüno and The Hangover?