If movies were the supreme art of the 20th- and early-21st centuries, then the icons they couldn’t capture are the exceptions that prove the rule. For every film that spent decades in development and finally got made and was hugely successful in one way or another—Deadpool, American Psycho, Mad Max: Fury Road—there are dozens more examples that haven’t and likely never will be produced: A Confederacy of Dunces, Blood Meridian, The Secret History. Those are all “un-filmable” novels, just like The English Patient and American Psycho. Properties often languish simply because expectations are too high, and the risks are too great: look at Brian De Palma and The Bonfire of the Vanities, or the 2019 adaptation of Donna Tartt’s The Goldfinch. Sequels and biopics fare no better: Bad Santa 2 and Zoolander 2 are a stain on their classic originals, and Warren Beatty’s nutty Howard Hughes movie Rules Don’t Apply came and went without a trace in 2016.

Great expectations come if the story has already been told: with so many episodes of Family Guy, why make a movie? Ditto for The Simpsons (South Park avoided this problem by making their movie just two years after the show’s debut). What about stars of other signs? The life and times of Joan Didion would make a great movie, but I doubt it’d make Barbie bucks; writers, especially novelists, have rarely made for compelling cinematic subjects. Musicians are a different story: while the camera has little regard for the solitary writer, it craves the form and movement of the singer, the dancer, the rock star. If cinema has failed to capture any medium, it’s rock music. I found this out in my early-teens: a great movie and a great show are not the same. At the time, music was much more exciting to me, and as I began playing and participating in it, more and more I found the movies’ depiction of music and musicians to be painfully square and 15 years too late.

Look at Jennifer’s Body: Karyn Kusama’s 2009 cult classic features Adam Brody fronting a murderous pop punk band. They don’t just fuck underage girls, their suck their blood: Megan Fox becomes a succubus after being “sacrificed” by the band and their occult crazies. But she was only a “backdoor virgin,” meaning she simply became possessed. All of this makes for a great indictment of the sexual politics and ethics of independent musicians, but the fake band Low Shoulder is a dud, so you can only go so far with characters who’d risk their lives and souls for them. Ditto Alex Ross Perry’s Hole-in-everything-but-name-only Her Smell, a fine film with prefab mall rock. No matter how moving that piano scene is, the rest of the movie’s music drowns it out.

As for the titans of popular music, the only successful movie is the one that comes out in the midst of their initial success: Prince and Purple Rain, The Beatles and A Hard Day’s Night, Eminem and 8 Mile. All of these films feature rock stars playing themselves, or very close versions of themselves; successful musician biopics made after the deaths of their subjects like Ray and Walk the Line follow a formula so familiar and tired that they were mocked in a successful 2007 spoof, Walk Hard: The Dewey Cox Story. That movie killed the Hollywood musician biopic for at least a decade, until Bohemian Rhapsody and Rocketman reared their ugly heads. Baz Luhrmann’s Elvis is the first movie about a famous musician that I’ve liked at all since Todd Haynes’ Bob Dylan mosaic I’m Not There in 2007.

But the one that always mystified me was Kurt Cobain. Why wasn’t there a Nirvana movie? The seven-year arc of the band, from suburban Washington basement shows to worldwide fame and stadium tours to a tragic and mysterious end—you can already see it, and that’s exactly what a movie like this is so hard to do. Everyone can see it, because they already have: the cinema doesn’t need to condense or address Cobain because his life and music were sufficiently well-documented while he was alive. Fans of his largely aren’t interested in a Hollywood rendering of his dreary childhood in Montesano or his crippling heroin addiction. Courtney Love said that Brad Pitt “chased” Cobain in the early-1990s, convinced he was “born to play Kurt,” but it didn’t happen, and now it never will. I think Robert De Niro as Travis Bickle in Taxi Driver is as close to a physical resemblance to Cobain as the cinema will ever get (compare the scene of him alone in the porno theater with the early 1993 South America Nirvana shows).

Besides the prohibitive cost of licensing songs, most movies simply don’t live up to most Beatles songs, or most Nirvana songs. I rarely see them used in film or television, and I don’t think it’s just because of the cost: they grab your attention to a fault. There was an episode of Succession that used “Rape Me” diegetically—a disgruntled employee set up Sarah Snook’s Shiv for embarrassment on stage as she tried to explain away her father’s policy of protecting rapists—and it worked, because that’s likely the song that would be used in real life in a similar situation. It wouldn’t have worked if it had played over the end credits.

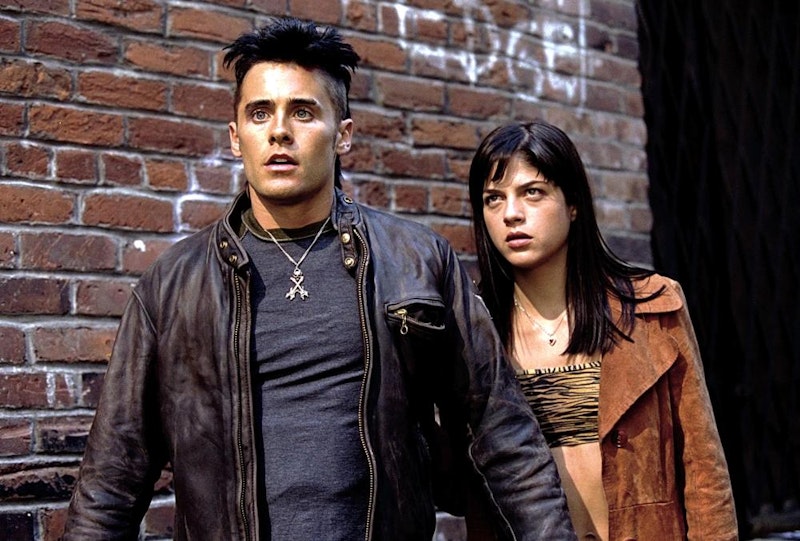

As for Cobain’s presence in other films, it’s nil: Gus Van Sant’s Last Days is a fine film if you forget that it’s loosely based on Cobain’s final days; Brett Morgen’s Montage of Heck is a good documentary, but there are plenty of Nirvana documentaries good and bad; and the 2002 curio Highway, starring Jared Leto, Jake Gyllenhaal, and Selma Blair as “three misfits” making a pilgrimage to Seattle on the day that Cobain’s body was discovered. Keep in mind his name isn’t even mentioned until 42 minutes into this 97-minute film, and that the first half is an unremarkable Boogie Nights/Goodfellas/Tarantino rip-off (screenwriter Scott Rosenberg’s first produced screenplay, 1995’s Things to Do in Denver When You’re Dead, is a notable Pulp Fiction cash-in).

Besides the fact that none of the main characters really care about Cobain, Nirvana, or any other alternative rock bands of the time, they barely talk about him. The most deflating thing about Highway and all other movies that try to capture or portray the work of a great musician is its score. Rich Robinson of The Black Crowes wrote the music for Highway, and its opening five minutes are thrilling—but it’s not Nirvana, and simply by invoking Cobain’s name, every guitar on that soundtrack is denuded of the power it could’ve had. If the greatest virtue of cinema is to record and preserve, to show us something we’ve never experienced before, any movie about a great musician is bound to fail without complete integration of the music in question. I’m not the biggest Roger Waters fan, but The Wall is a great rock movie, as is Purple Rain. These are movies that record and preserve musicians properly, some of the only ones that can live up to their subjects.

—Follow Nicky Smith on Twitter: @nickyotissmith