When Alfred Hitchcock died in 1980, he was bitter, tired, and delusional, like most directors at the end of their lives. He never made another movie after 1976’s Family Plot, but the late-1970s through the 1980s was high time for anything “Hitchcockian.” Naturally, the artist didn’t live to see the full fruits of his labor, nor to see his reputation burnished by ever-younger directors not just citing and applauding him but paraphrasing him, as with Brian De Palma’s Obsession, Dressed to Kill, and Body Double. De Palma’s schematic thrillers and their style are well-known, but what about Curtis Hanson’s The Bedroom Window? Or Still of the Night by Robert Benton? Not to mention the late-1970s remakes of 1930s Hitchcock movies like The 39 Steps and The Lady Vanishes. Hanson’s film is dead in the water due to a stiff Steve Gutenberg lead performance, and Still of the Night is rudderless, in Meryl Streep’s words, “the worst film I’ve ever been in.”

After Stanley Kubrick’s death in 1999, the same thing happened: another successful but nevertheless underappreciated cinematic genius shuffles off, and all of a sudden his “style” is everywhere. But as with Hitchcock, as with everyone, it’s a reduction, distillate. Sometimes it works: Jonathan Glazer’s Birth is a thoroughly “Kubrickian” film that understands what that term means. Ditto for Todd Field’s three films, despite the middle of the road upper middle class literary fiction source material for In the Bedroom and Little Children. “Kubrickian” can mean so much: very wide lenses and very long lenses, long Steadicam takes that follow or lead, classical music, and real ambiguity, no cop-outs. Is that kid lying in Birth, or is he Nicole Kidman’s dead husband? I still don’t know.

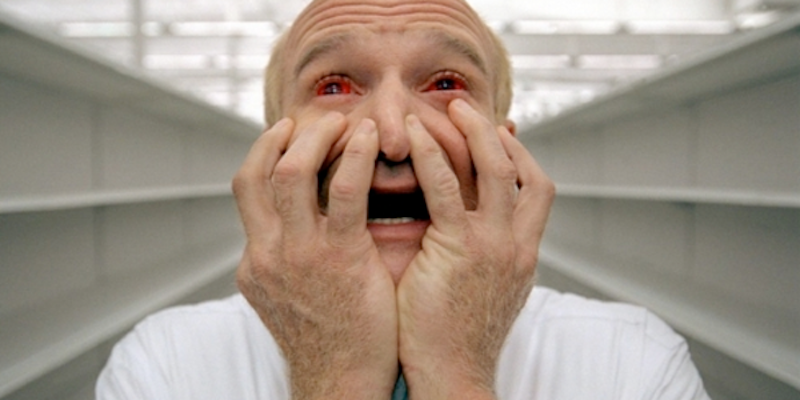

Not the same for One Hour Photo, Mark Romanek’s 2002 drama about a photo technician obsessed with the family of one of his customers. Robin Williams plays Sy the Photo Guy against type, much like Adam Sandler in that year’s Punch-Drunk Love. Williams was a fine dramatic actor, even in schlock like Good Will Hunting, and he’s as good as he can be in One Hour Photo. But for anyone who wants a lesson in what “Kubrickian” means in practice, watch One Hour Photo. Precise camera moves, a cold and sterile environment, man vs. technology, paralyzing dread… all undercut and finally killed by the stock movie string score. The film’s other big fault—Sy indirectly revealing he was molested as a child—destroys any power Williams might’ve summoned with his performance. This obsessive weirdo is just another sexual abuse victim, traumatized for life, like millions of other Americans. Not exactly Jack Nicholson in The Shining, or even Alex DeLarge.

One Hour Photo was a hit, apparently, and for whatever reason I never got around to watching it as a young kid or teenager. It came out in the last great period for independent American cinema, when Sundance films cost $10 million. The poster lingered in my mind for a while, and I knew I’d get around to it eventually, but then again, how could it top Williams’ excellent heel turn in another 2002 movie, Death to Smoochy? I’m not surprised One Hour Photo hasn’t endured like Punch-Drunk Love, Collateral, or Lost in Translation for its against type performance. It’s the kind of movie that might be made today, an empty attempt by a music video director to ape Stanley Kubrick’s style without anything compelling, much less inspiring.

—Follow Nicky Smith on Twitter: @nickyotissmith