In the aftermath of World War II American popular culture knew who the bad guys were. Men who went to fight in Europe in the 1940s came home and went on to create TV shows, comics, novels, and movies in which fascism was a clear evil. Sometimes that meant fighting at the hands of superheroes. Sometimes it meant a mental struggle with the temptation fascism held for supposedly civilized people.

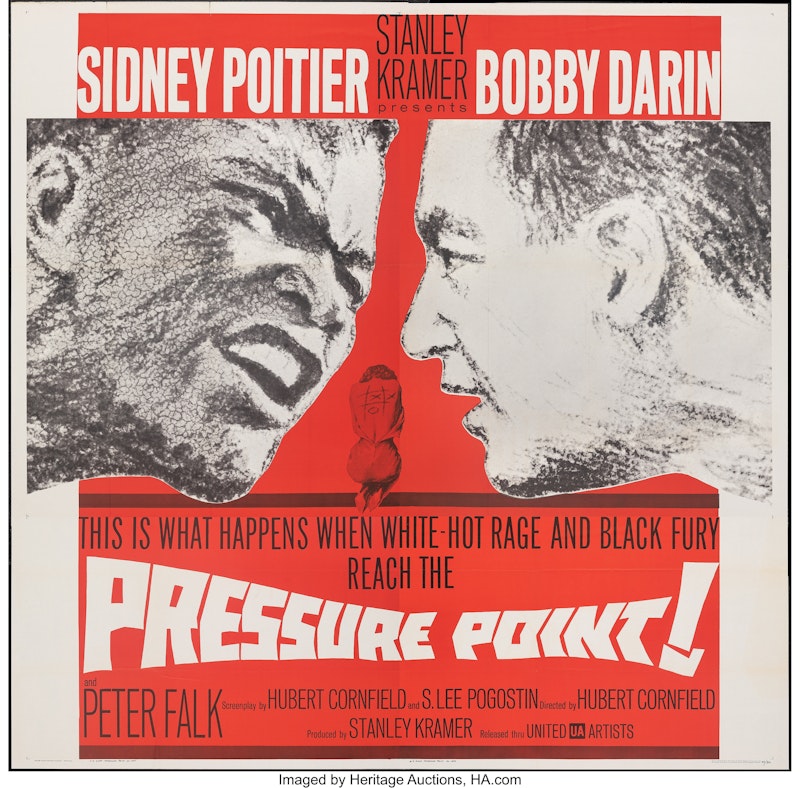

A few decades on, fascism’s on the rise again and if some of those post-war stories look merely well-intentioned, others look prescient. Thus Pressure Point, eighth in the Criterion Channel’s “Frame of Mind” showcase. Directed by Hubert Cornfield from a script he wrote with S. Lee Pogostin based on “Destiny’s Tot” by Robert Lindner, it’s a thoughtful story about a Black psychiatrist analyzing an American fascist just before World War II. It does a lot of things very well, some poorly, and has a sting in the end that couldn’t have been anticipated when the movie was released in 1962.

A framing sequence shows a young psychiatrist (Peter Falk) complaining to his superior (Sidney Poitier) that he can’t get through to his new patient, a Black youth who hates Whites, and asking for reassignment. Poitier tells him the story of his experience a couple of decades earlier, when he was a prison psychiatrist assigned the case of a young fascist (Bobby Darin) who hated Blacks. That story makes up the film, an extended battle between therapist and patient.

The patient (never named) gets parole over the objections of the therapist (also never named), and then meets him one last time. The patient knows his Whiteness got him freed by the authorities, and wants to rub the doctor’s nose in it. In response Poitier’s therapist gives an impassioned speech about America and its commitment to justice. It’s a powerful moment, mainly because of Poitier. You believe the doctor believes what he’s saying, but there’s also a strong sense of near-berserk desperation, a man clinging to his beliefs and hopes in the face of evidence to the contrary.

The film was based on the writing of Robert Lindner, a psychiatrist whose 1955 book The Fifty-Minute Hour presented a series of case histories of his patients. One of those histories described “Anton,” an American fascist who had been the Jewish Lindner’s patient when Lindner worked in the prison system during World War II. Lindner died in 1956, but S. Lee Pogostin adapted “Destiny’s Tot” into a TV teleplay in 1960. Producer Stanley Kramer took that script and had it reworked to make the psychiatrist a Black man, to be played by Poitier, who he’d directed in 1958's The Defiant Ones.

(Lindner was an interesting figure, who mixed hypnosis with psychoanalysis in a way that defied psychoanalytical convention. His 1944 case study Rebel Without a Cause gave a title but very little else to the famous film, while another case study in The Fifty-Minute Hour, “The Jet-Propelled Couch,” described his analysis of a government scientist who may have been the science-fiction author Cordwainer Smith.)

Lindner’s actual experience was altered significantly to make the material fit the new shape of the story. The fictional doctor’s experience as a Black man is underexplored, though there’s enough of a backstory given to make his position at least somewhat credible; if he’s written as reacting too quickly to the patient’s insults, Poitier’s performance at least is exemplary. And Darin’s fascist is almost eerie in his believability, a bundle of hate and unresolved issues. He accepts a Black psychiatrist too easily. But Darin gets an awful lot out of the script, dealing with Poitier with an easy patronizing superiority that sometimes slips over one way into contempt and another way into a desperate pleading for some kind of acknowledgement.

The psychiatrist brings out his patient’s issues with his father, an easy theme for Hollywood then as now, but it rings true here because of the fascist obsession with patriarchal authority. Fascists cast their leader-figures as strict fathers, and the film’s parallel between political and personal family neuroses is effective. The film moves in and out of flashbacks to the patient’s childhood, sometimes using the child who plays the patient as a boy (Barry Gordon) in the “present” to show the adult patient’s regression to childhood. That’s a strong visual idea, and it works with dream sequences and dumb shows to give an unsettling, surreal tinge to the movie.

Pressure Point’s representation of psychiatry revolves around the conflict in the relationship of patient and doctor, but it’s an unconventional conflict. Poitier’s character seems to spend much of the movie hanging on to his ideals and his hope for America, culminating in his final speech. He’s working to heal the patient, but it’s difficult to see what that means. He rarely challenges the patient’s ideology directly, and there’s the disturbing sense he may after all only be building a more efficient and less conflicted fascist. The drama of the film, then, somewhat undercut by the framing sequence, is whether the doctor will come to doubt his own authority—to doubt the power structure that’s set him above the patient, and to doubt the potential for America to be redeemed from Americans eager for fascism.

The psychiatry’s oversimplified, but the linkage of politics to psychiatry works—the struggle to figure out what warped element in someone’s personality turns them to fascism. Individual issues aside, the film also understands something of the structural challenge of fascism to democracy; a speech where the patient lays out to the doctor how fascism will grow in America is disturbingly credible. The ending’s not a clear victory. The patient walks away, and we’re told he was later hanged. But the framing sequence suggests that decades later the doctor’s still testing his faith in America, still trying to convince himself that fascism’s not a core part of American identity. Today, so are a lot of people.