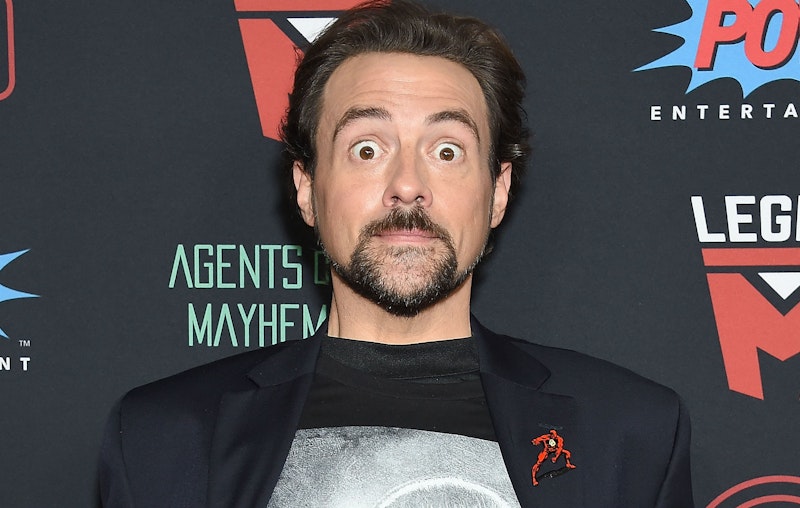

Glandular, gelatinous, and gross, Kevin Smith wouldn’t have a career but for Harvey Weinstein’s financial support. By career, I mean a series of bad to inexplicably extant “films” that elude extinction. Smith’s oeuvre survives within the digital realm of ones and zeros, a Matrix-like line of code that would make the most indulgent fanboy reach for the nearest blue pill, in bullet time, so as to forget Smith’s role as writer, director, and supporting actor in cinematic garbage.

Smith, who survived a heart attack, is a self-described entertainer, not a filmmaker. That he’s half-right is no excuse for his portrayal of New Jersey: the backdrop for his home videos in the form of commercial motion pictures, where, despite the help of an Academy Award-winning cinematographer, Smith fails to entertain.

From the roll-up door outside a convenience store to the front counter inside, Smith fixes his tripod on a day in the lives of the store’s clerks, Dante Hicks and Randal Graves, whose names are as subtle as the giant metal letters atop any TRUMP-branded hotel, tower, or casino. The result is Clerks: Smith’s 10th circle of Hell, a bull session about pot, “Star Wars,” dating, and oral sex.

Had Smith died then, had he flatlined in an ambulance en route to Riverview Medical Center in Red Bank, New Jersey, while EMT workers shocked his chest with a pair of defibrillator paddles, the world would have been spared Mallrats, Smith’s second film in his New Jersey series—which he shot in the northwesternmost part of the state, Eden Prairie, Minnesota.

Forget Paramus, New Jersey, with its five major indoor shopping centers, including the largest mall in the state. Forget the look and feel of the area, with its cloverleaf interchange and flyover ramps, where the roads run alongside supermarkets, gyms, hamburger stands, shoe stores, car dealerships, office parks, and acres of parking spots. Forget exterior shots of New Jersey altogether, and pretend that Smith’s “New Jersey” is the real thing.

Pretend we must, because Smith is not a filmmaker. He’s a writer, albeit one with sound equipment designed to translate the keystrokes on Quentin Tarantino’s laptop into repartee about popular music, comic books, and Superman’s penis.

What he doesn’t write is original content, because his bit about astrobiology and Superman’s faster-than-a-speeding-bullet spermatozoon, which, were it not to impregnate Lois Lane, would leave an exit wound in her pelvis the size not of Smallville but Metropolis. Smith solves this problem by introducing the Kryptonite condom. Then, in an act within an act, billed as “An Evening with Kevin Smith,” where, dressed in oversized cargo shorts, gray socks, black sneakers, and a t-shirt and hooded sweatshirt ensemble, Smith—in his round frame eyeglasses, like an obese Harry Potter at a Weight Watchers meeting—connects his fictional prophylactic to his draft screenplay for a Superman reboot.

By playing “Kevin Smith,” he publicizes his purported genius as a writer while mocking the likes of producer Jon Peters and director Tim Burton. He also doesn’t mention an essay (“Man of Steel, Woman of Kleenex”) by Larry Niven. Published in 1969 and posted to Usenet in 1986, the piece is a seminal tract (pun intended) about Superman’s need to refrain.

Smith nonetheless cites the Kryptonite condom as the moment when a studio executive at Warner Brothers said: “This guy [Smith] seems to know a lot about Superman.” Smith then tells several funny but one-sided stories about Peters, ending with his (Smith’s) departure from the project, the hiring of Burton, and the shelving of Smith’s script for Superman Lives.

Unwilling to be the bigger man, perhaps because he is (or was, until his botched attempt to reenact the death of Jonathan Kent) the bigger man, Smith trashes Burton’s work on Beetlejuice and Batman instead. By implication, Smith attacks the writers of these films, his betters by incalculable orders of range and style, as well as the star of both titular characters: Michael Keaton. Not only is Keaton Batman, his Beetlejuice (or Betelgeuse) is a great Joker. As a performer, Keaton does what no member of Smith’s repertory, including Ben Affleck, can do: act.

With his pale skin, dark eye circles, green hair, broken nose, swollen lips, and rotting teeth, Beetlejuice is a supervillain in a black-and-white striped suit. A “bio-exorcist,” who advertises in The Afterlife, he’s a graduate of Juilliard and the Harvard Business School. A master of deadpan, he’s a miscreant with moss-covered flesh. He’s a part of Burton’s surrealistic universe of sandworms, snakes, ghosts, and demons.

He’s also too complex for any Smith see, Smith do techniques of positive reinforcement, because no matter how long Smith shakes his typewriter and shrieks—regardless of how often or far he hurls his waste—Smith cannot escape the limits of fate.

We can, however, avoid Kevin Smith.