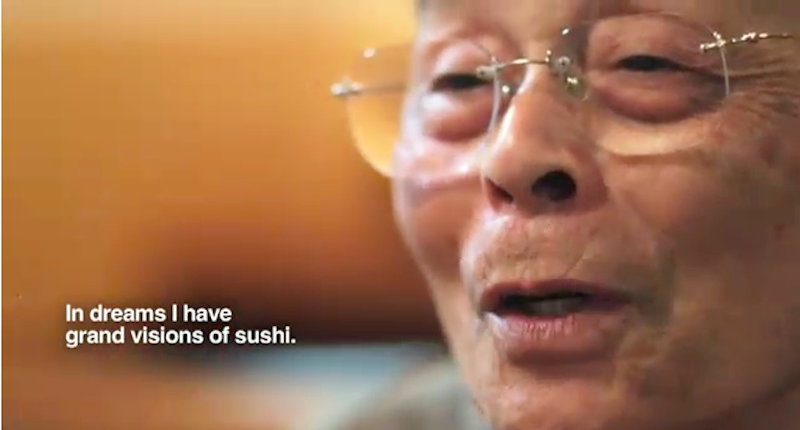

Jiro Dreams of Sushi (2011), a documentary about Jiro Ono, an 85-year-old sushi chef and owner of a Michelin three-star sushi restaurant located inside a Japanese subway station, is, despite the Zen-like philosophical resolve director David Gelb projects, a very grim and depressing movie, when seen from the lens of not its celebrated protagonist, but his eldest son. The film is beautifully shot—consistently using slow-motion and tilt-shifts to elevate, or at least glorify, sushi's technique to another worldly realm—and its ultimate message is a good thing we should all remind ourselves: be humble, work hard, keep working.

The snag, however, is the story of Jiro's eldest son, Yoshikazu, the natural successor of Jiro's restaurant, now in his 50s, who's been working under his father since he was 17. Yoshikaza and his younger brother Takashi began working for their father as teens instead of going to college; the gentle implication is they were forced to, though Jiro's account of it was mere stern encouragement. Takashi has his own sushi restaurant, a perfect mirror of Jiro's (both for conceptual and practical reasons; Takashi and Jiro are right- and left-handed, respectively), and is clearly the happier of the two bothers. Yoshikazu carries a pudgy layer around him, under which a sad force peeks out to somberly address the endless minutiae of sushi making. He seems less inspired than resigned.

In one scene, most memorable for me, Yoshikazu is seen seated—shot from a distance, the way one films a bear—in the subway station just outside the restaurant flapping sheets of nori above a charcoal grill in order to smoke it ever so faintly. His movements are robotic, almost unconscious, a bald head bent over the process, and one imagines three decades of this. The film's conceit is exactly this kind of exotically Oriental work ethic or near spirituality, as if we were witnessing some monk in prayer—and while this may seem beautiful, and aesthetically is, at no time have we, nor Jiro, asked him if he'd simply rather get some ramen with a date. There is no mention of wives or any women, ever, this Ono family sausage fest undoubtedly manually tenderized, like their octopus.

As for the sushi, it's probably amazing, though the ¥30,000 ($384.61) 20-piece experience is a little too steep for me. The cost of something informs its value and one's perception of it. The fish may be the freshest in the world, supplied by the most instinctive dealer, chosen by the most experienced chef, cut by the sharpest knife, by the most deft hand, served in the perfect order, at the perfect time and temperature, but in the end, it's just raw fish. It may be Zen, or it may be marketing. For $384, I'd want a filet mignon accompanied by a cow with a hole in its side, an entire bottle of wine, chocolate soufflé, and the waitress to come home with me.

In a reunion Gelb undoubtedly arranged for "material," Jiro visits his hometown to see his childhood friends, who regale us with tales of how Jiro was actually once a bully. This is far less than shocking, given Jiro's severely domineering demeanor even at such an old frail age. The man is a tyrant. A knife so sharp you can't feel it enter. His father died when he was seven and apparently he just went off on his own; there is no mention of his mother. The patriarchy is so intact, or deluded, it doesn't need women. Jiro smiles at once being a bully and mentions something about how he's changed, how sushi changed him. Everyone smiles and quickly nods to mitigate an odd tension, except for his son, who looks silently at the floor.