Baltimore filmmaker Matt Porterfield has gotten a lot of acclaim for his films Hamilton (2006) and this year's Putty Hill, which premiered at the Berlin International Film Festival and screened at several others, including the Maryland Film Festival three weeks ago. Porterfield's films focus on Baltimore youth, particularly in working class neighborhoods he's been fond of since childhood. Putty Hill has a unique approach to storytelling: based around the narrative of a young man who died of an overdose, Porterfield gave freedom to untrained actors to help invent the story themselves; through interview-style questionings by a disembodied voice, these teenagers and a few adults sit and talk, as though the story were a part of their lives.

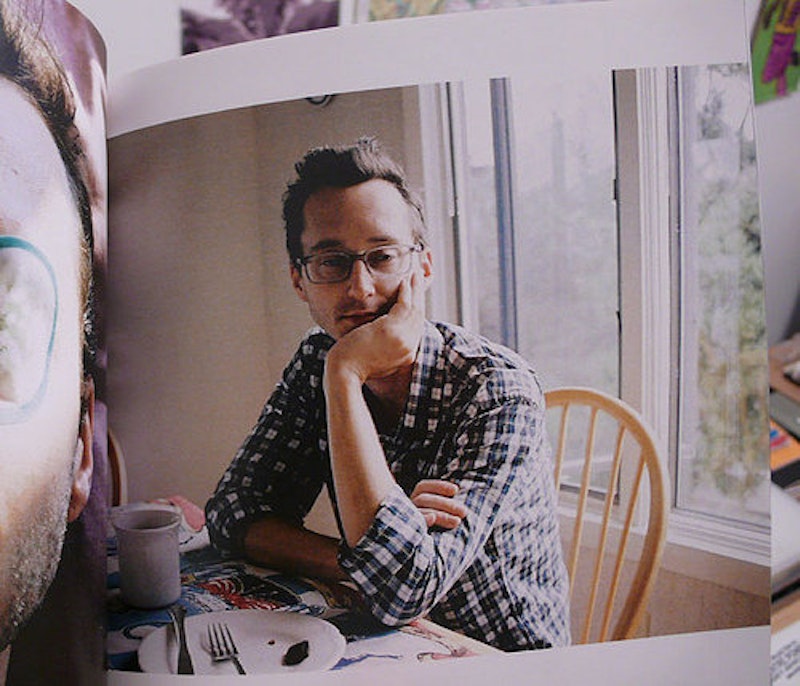

Porterfield, 33, teaches screenwriting and production at Johns Hopkins. Two days ago, The Cinema Guild announced that it acquired the distribution rights to both Putty Hill and Hamilton; Putty Hill is opening in theaters this fall, and a DVD of Hamilton comes out in early 2011. I interviewed Porterfield at his house in Charles Village, as he was in the process of moving to New York for the next month or so.

Splice Today: How did you derive your process of blurring the line between documentary and fiction?

Matt Porterfield: I think because I'm interested in narrative realism, and self-conscious about it, about the relationship between the filmmaker and his or her subject, and the sort of innate power relationship there. I'm always thinking about ways to attempt a cinematic truth-value through collaboration. I've been thinking about making a more traditional narrative film—like this project Metal Gods which we had to abandon because we couldn't find financing for it. In the process I met a number of people I thought would be really good onscreen. In shaping the scenario that became Putty Hill, it was very much about them and their stories. I thought they were interesting subjects, and just wanted to see them in space, see them move and talk. So it was less about trying to come up with a fictional narrative to fit them into. It was rather the opposite: to craft a narrative that was shaped around them and by them through our collaboration.

ST: So Metal Gods had a full script?

MP: It was a 110-page script I'd been working on for a couple years. Hamilton, my first film, was scripted, so I was pushing further in this direction of narrative realism. But we were thinking about how to throw something together, after abandoning Metal Gods, with the pieces we already had in place: the cast, locations, some themes, and Baltimore as a backdrop. I started to look towards some documentaries and films that blur the line between documentary and fiction. Streetwise, which is a film about Seattle street kids, made in 1984 by Mary Ellen Mark and Martin Bell, was an inspiration for Metal Gods and in turn Putty Hill. Also, the films of this Portugese filmmaker Pedro Costa; in particular a film called In Vanda's Room. Some of Costa's films were just released as a trilogy on Criterion—they're all set in Fontainhas, which is a slum of Lisbon. I totally recommend it.

ST: You found a lot of your Putty Hill actors in public. How would you know, meeting someone, whether you'd want to use them?

MP: A lot of the actors were found through this network of casting calls that we put into place; we were handing out flyers on the street, using MySpace, holding auditions at various schools and churches. But occasionally I'd run into someone on the street, and would be intrigued by their physicality, they way they looked and moved—Spike [Sauers], for example, who plays Sky [Ferreira's] father, the tattoo artist. I found him at a bar on Harford Rd., around the corner from where I grew up. Typically when that happens I'll just ask if they want to be in a movie, and usually at least a conversation comes out of it.

When I've auditioned someone properly—recorded the audition—I'll go back and watch, and maybe there's a spark in the moment when they're reading lines or just speaking. Sometimes I'll find someone intruiging or interesting but can't tell if they're necessarily filmic until I go back to look at the tape. I'll notice things about the person I wouldn't otherwise. It's like the camera sort of objectifies them. So it's a combination of what happens in the moment and how a person takes direction, whether they can take the material that I've written, or attempt an improvisation with any kind of emotional honesty. Those sort of things.

ST: So how much do you ask them to be themselves, and put their own experience upon whatever guidelines or story you've given them?

MP: Completely. I mean, it's to the extent that they're comfortable. I made it pretty clear for this scenario, for Putty Hill, that I was interested in them. Both in the interviews and in the more fictive scenes, the narrative scenes, they were free to be themselves, they were free to answer questions as themselves. When asked a question that was more part of the narrative of the film—the Cory narrative, the fictional element that ties everything together—I'd ask them to draw on their own experience, and they were all able to do that, too. In the narrative scenes, I'd typically put them in places that were familiar to them, like their own homes, or places they frequent, and I'd try to populate the scene with other people they knew. Which I think just all adds to increase the comfort level of the performer, and if they're nonprofessional that's really essential, I think. They need to feel safe.

ST: In your interview with the Baltimore Sun you said that portrayal of adolescents and kids is important to you, because of the way dominant culture tends to distort them in movies and TV. Could you talk a little more about that distortion?

MP: I feel like, in the last 10 years, teenagers, adolescents and young adults have been identified as a real target market. Young people now have more expendable income than ever before, so there's a lot of media generated for this audience. This perpetuates a few things: the hegemony of capitalism and consumer culture, but also old stereotypes. Too much of the content created for young people has themes that are actually regressive; in some cases they're too adult, in other cases they're totally condescending.

We tell the same old stories across the board in film and television, whether they're geared towards women in their 30s, or preteens, or men between the ages of 35 and 50. We have these ideas of what target audiences respond to, and at least in the United States we continue to commodify culture and the audience at the same time. And when it comes to the portrayals of young people in film and television, because the industry is based in California we get these images of opulence, of materialism, that support this dream of attaining wealth and status. These portrayals actually, in terms of character and environment, depict a very small portion of the way people are living. So my goal is to make films about precise locales and the people that inhabit them, and hope these local scenes have a universal appeal, can find resonance and weight with, you know, young people who go to White Marsh Mall to see a movie.

ST: At Berlin, do you think it resonated as something universal? Or did they read it as a case study of Baltimore specifically?

MP: When the film's played in another country, as an export, it either works or doesn't, but on a different level. I think my films are particular enough that they depict a uniquely American experience, but of course, overall, the world has its eyes on America and American media, so there's a fascination with anything that depicts a subset of American culture that they haven't seen before. There's a fascination overseas with The Wire and The Corner. I don't think all themes necessarily translate. And that's okay. I hope people engage with the film in a way that's not purely voyeuristic. But I have read reviews in foreign-language press that are sort of reductive and refer to it as like white-trash America, which really irks me. It's not across the board, though.

ST: Speaking of voyeurism, what do you think of critiques of "exploitation" in films like yours?

MP: I haven't heard that, but I'm aware of it. Nobody has openly called Putty Hill or Hamilton out in that way, and I hope that we operate above that. But I'm certainly very conscious of the potential for exploitation when you're portraying a community that you're not necessarily a part of, that you know but you don't fully inhabit, whether you're dealing with the community or the individual. It goes back to that power relationship between the person filming and the subject filmed. It's a fine line, and a question that I hope I'm continually asking myself as I make films like these.

ST: Do you think Baltimore has changed significantly since your childhood? Would scenes in your films have happened differently 15-20 years ago?

MP: When I was growing up in Northeast Baltimore, where I shot my first film Hamilton, it wasn't really ethnically diverse at all. It was all white. I left in '95 to go to school in New York, and was there for seven years. When I'd come home to visit my dad, who still lived in the house I grew up in, more African-American families were moving into Hamilton. That was actually creating some tension; I'd talk to my neighbors, the kids I grew up with, and there wasn't overt racism, but there was an undercurrent that the neighborhood was changing for the worse. So now Baltimore is diversified, which I think is a good thing; this has happened throughout working-class areas of the city. Through that exposure to diversity, young people are more open and less hung up on race than kids were 15 years ago.

Another difference is how connected young people are through technology. They have much more access to things they're interested in. It was harder for me and my friends growing up to access subculture, like dress, design, music, art. Now young people have access to so much style through the Internet.

ST: What about Baltimore culturally and artistically? How has that changed?

MP: It goes through waves. Baltimore's always had a lot of artists, because of its proximity to New York and low cost of living. My dad tells stories about the community underground theater he was involved in, in the 70s. I think Baltimore culture will always remain underground, and go through little revolutions. Since I moved back here in '02, the music scene here has really fed everything else, and recieved a lot of attention nationally and internationally. Kids who do fine arts are also in bands, designing posters, batch-printing books. I think it's a good scene. I wish there were more people making film, but who knows? I could see that changing too.

ST: Is metal important to you?

MP: It is. I didn't grow up a metalhead, but it was the dominant music in my neighborhood. It symbolizes something for me; it's nostalgic, visceral. Connected to memory, but also emotional, working class. As a genre of music, as a subculture, it exemplifies everything I'm interested in. Even though at the time, when I was a skater, we listened to punk and hardcore, and maybe where they met with metal it'd be like thrash and speed metal. Now, I can totally embrace glam as easily as Pantera or Slayer or Megadeath.

ST: For future productions, you said you'd like to do more-narrative based work. What else would you like to do that you haven't yet?

MP: I think I want to make one more Baltimore film, to sort of complete a trilogy. I'd like to shoot that next summer. But there're some other projects that would push me in different directions. Two adapdations that I'm interested in: one is Ivan Turgenev's First Love, and the other is a verse novel by the poet Anne Carson. I'd like to shoot a film on Maryland's Eastern Shore, and then I'd like to do a film in another city. As long as I keep challenging myself. I would like to push in a more traditional narrative direction, like work with professional actors. I feel like I'm ready. It might be fun to also push in the opposite direction, and make a documentary.

ST: With First Love, would you put it in a Baltimore or Maryland setting, or at least in the US?

MP: I started to work on it, and yeah, it's set in Maryland. I don't think it has to be. I would want it to be contemporary. That would be the biggest challenge, because it's from a particular time. But it's a book that's just always struck me, since I read it when I was 16. It would be interesting to see how to retain more than the seed, like actually adapt the novel. There's so much there that's dark, and I wouldn't want to lose that in trying to make it more accessible. So I think that one would take some time and study. There's this incredible twist in the end that just throws everything upside down, and it would be really hard to treat in a contemporary retelling of the narrative. I don't actually know if you could pull it off, that's the fucked up thing, like, I don't know how modern audiences would respond. But that challenge really interests me.

ST: With storytelling, which other writers and directors are influences?

MP: I think back to playwrights in particular who influenced my approach in crafting dialogue for film, like Pinter and Beckett. I like the rhythm of their plays. Ionesco is more absurd, but I've always taken him as well. I like pauses, the minimalist approach to dialogue, in Pinter in particular. William Burroughs is probably my favorite writer, because he has a real knack for purely visual language. It's like a direct connection to my visual cortex. I'm not interested in crafting filmic narrative like his, but I'm really interested in the way he works with language; the images he conjures are really inspiring. He almost doesn't need narrative, because of this sort of strobic, flickering effect of layering image upon image.

For directors, I'm influenced by some of the big names of the Nouvelle Vague: Bresson—but he's really of an older generation—and Godard. I continually watch everything Godard puts out. Pedro Costa, who I mentioned. I love David Lynch. His worlds are lush, and his approach to narrative is a direct influence on mine. I mean, I don't practice transcendental meditation, but there's that dream state you enter into, where you're allowing your imagination to run and honoring ideas that just come from nowhere, and he does that better than anybody else.

ST: If you had a huge budget, and you were using professional actors, what would that give you specifically?

MP: I think it would be more limiting in almost every way. I can't speak from experience, but knowing enough about the industry and how things work when more moneyed interests are involved and the stakes are higher, you're more and more limited. But because I've never had a lot of money to make a film, I'm good at working within imposed limitations, whether they're imposed by the economy of the project, or self-imposed. I like limitations, I like framework. So I feel like it'd just be another set of limitations. I'd have different forces to answer to, I'd have more people to please, I'd have talent with higher expectations and demands. But I like working with people, and that's probably why I make films.

Creatively it'd be really interesting, with a bigger budget. Because you can pay so many people, if you can dream up something it can be articulated by someone; there's someone who can do this thing you've imagined. That must be really fun. James Cameron is a highly technical director: he gets himself really involved in the mechanics behind the effects that make his films, he gets off on that. I wouldn't. But I can imagine getting off on coming up with an idea for something, whether it's a puzzle for the art director, or involving some pyrotechnics or special effects.

But also when you work on a higher budget, the division of labor is increased. One of the things I've enjoyed on production of the first two films I've made is that it's really felt collaborative; the lines were blurred. So the AC is also head gaffer, we have someone who's doing digi-tech but also setting up lights, and the art department is running to get coffee if they have to. Everybody's willing to pull whatever weight needs pulling, and on a big production that's really hard to cross those lines.