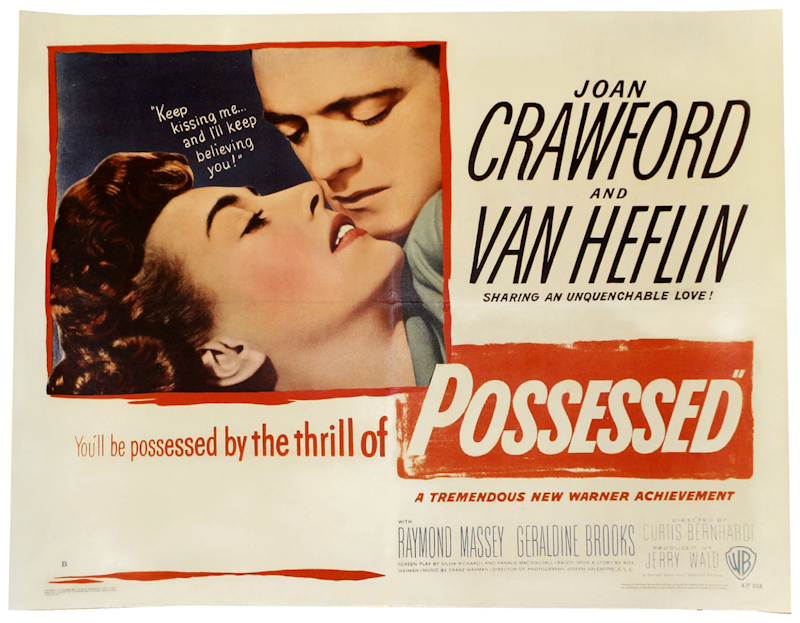

It’s conventional to describe a psychotherapist as a modern shaman, a magician-priest who leads a patient into the depths of the subconscious and back. You can hear something like it as early as the 1947 movie Possessed, the second movie in the Criterion Channel’s “Frame of Mind” collection of films with plots incorporating psychiatry and psychology.

A noirish melodrama starring Joan Crawford, towards the end of the movie a psychiatrist reflects that when a person suffers a mental breakdown “in the Biblical sense, we might say that such a person is possessed of devils, and it is the psychiatrist that must cast them out.” It’s a messianic proclamation, recalling Christ and the Gadarene swine, fitting given the authority the film invests in psychiatrists.

The movie begins with a woman (Crawford) wandering the streets of Los Angeles. She collapses, is taken to hospital, and eventually talks to a psychiatrist. We see her story unfold in flashback: the woman, Louise Howell, is the nurse to an older and richer woman named Pauline Graham (Nana Bryant) who believes Louise is carrying on an affair with her husband Dean (Raymond Massey). In fact, Louise is in love with the Grahams’ neighbor David Sutton (Van Heflin), but he doesn’t love her and coldly breaks off their relationship when he gets a job from Dean Graham on an oil field in Canada.

Louise is obsessed with David, but can’t stop him from leaving, not even when Pauline Graham dies. Louise is kept on by Dean Graham to look after his young son and 20-year-old daughter Carol (Geraldine Brooks), and eventually Dean proposes marriage. She doesn’t love him, but accepts, only for David to re-enter the picture—at which point Carol falls for him, and Louise’s sanity is pushed to the breaking point.

Possessed is a solid piece of work. Directed by Curtis Bernhardt, it was adapted by Ranald MacDougall and Silvia Richards from Rita Weiman’s novelette “One Man’s Secret.” It looks sharp; Joseph Valentine’s cinematography creates a gothic atmosphere, and the set design and set dressing are detailed and atmospheric. So’s the sound design, to an extent unusual for the 1940s, with a recurring musical piece helping to bring out Louise’s mental disintegration. Performances are strong, and if Crawford carries the picture, Van Heflin’s cynical roué almost steals it away from her.

Most importantly, the film’s structure works to set up a mystery, keeping you interested in learning how Louise gets to the point at which she started the picture. There’s genuine suspense that comes from the film being canny about what information it gives you and what it holds back and in what order it tells you things.

The movie’s a melodrama—plot-heavy, with characters either sympathetic or not—but wanders across genres. Romance elements are front and center, while the hints of violence and doubt about what actually happened create moments out of a thriller or suspense story. Louise’s mental decay and hallucinations lead to a horror-film atmosphere. And the frame sequence establishes the movie as a medical drama.

The psychiatrists in that frame story, led by self-proclaimed exorcist Doctor Willard (Stanley Ridges), assess Louise as schizoid and suffering from psychosis, giving a clinical description to her acts. It’s a more sophisticated use of psychological jargon than in 1939's Blind Alley because it doesn’t reduce human behavior to the twitching of a marionette, but tries to explain behavior by understanding the drives and stresses behind it.

Still, Louise kills a man while in a psychotic state, and under the Production Code, killers in American films had to be punished for their crime; so this movie concludes with the psychiatrist explaining Louise’s mental state to Dean Graham, comparing psychiatrists to priests, and telling Graham that with effort and struggle and mental pain she can be cured. The psychiatrist takes the place of a judge as well as clergy. Willard lays out how Louise will suffer for breaking the law, but also suggests she can and will be rehabilitated. If not an early sign of weakening in the Production Code, it’s at the least striking that psychiatry had become accepted enough that “not guilty by reason of insanity” was a verdict the Hays Office could tolerate.

Perhaps it helped that Louise Howell ends up under complete patriarchal control, her destiny to be determined by an older husband she doesn’t love and an aged psychiatrist who throughout the film has been in the role of her father confessor. But it’s notable that in a 1949 film Louise gets to kill a man who trifled with her affection, and doesn’t have to die or go to trial. When David’s shot we hear the gunfire, and see him from her perspective; from the waist up no wound appears, but he collapses and she shoots him again. Intended or not, the implication is that she shot him the first time in a place the Production Code wouldn't allow the film to show.

At any rate, the movie opens with Willard complaining about the rise of psychosis in the modern world and speculating that civilization is mentally unhealthy, so it’s possible to see Louise as a subversive element within the male power structure not just of the psychiatric hospital but of society as a whole: a symbol of reaction against a rationality embodied by male figures, like David Sutton (mathematician), like Dean Graham (a literal Dean and business tycoon), like Doctor Willard, who tries to impose logic on the illogical parts of the mind. The movie works because it can’t be reduced to simplistic readings, but also because it hints at that kind of symbolic overtone. The characters are complex, and Louise’s psychology is convincing, in clinical terms and otherwise.