In the late 19th-century, a short-lived literary movement sprung up in Scotland known as the Kailyard School. Often told through the eyes of a stranger, these stories usually depicted rural life in Scotland as quaint and palatial, with something innate imparted not only by the local villagers, but also the geography of the country, its highlands and shores. Scottish filmmaker Bill Forsyth explored these sentiments in 1983’s Local Hero. The film contains many elements that define an outsider’s perspective of Scotland; however, it subverts these ideas without downplaying the ineffable qualities of the land itself.

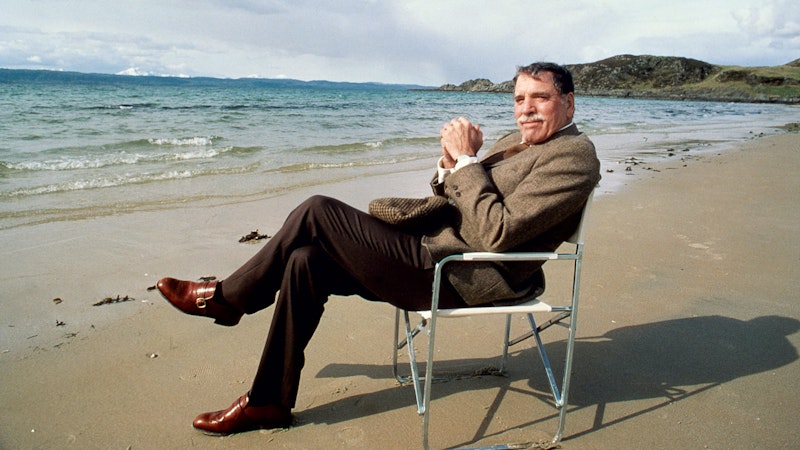

“Mac” MacIntyre (Peter Riegert) works for Knox Oil and Gas in Houston, and is the archetypal young and ambitious American executive of the 1980s. From tailored suits to his Porsche 930, Mac has surrounded himself with enough objects to exude a sense of value. But he’s romantically inept, socially uninteresting, and uses materialism to shield himself from emotional fulfillment. Felix Happer (Burt Lancaster) is the inheritor of Knox Oil and Gas—by all accounts, a rich and successful businessman. However, Happer takes little interest in the company. He seeks fulfillment through the stars, particularly his desire to discover a comet that he can name after himself. Despite their respective financial success, Mac and Happer are similarly spiritually adrift. With Knox planning to purchase land in Scotland to build a massive oil refinery, Mac is selected to close the deal in-person due to his Scottish-sounding name (there’s not a drop of Scottish blood in MacIntyre; his immigrant parents chose it to sound more American). Happer’s additional assignment for Mac—watch the skies for anything unusual—is quietly brushed aside as he plans to get in, close the deal, and get out.

When Mac arrives in the town of Ferness, it’s cloaked in an evening fog so thick he’s forced to stop his car for the night. This mystical quality introduces the fantastical perception of rural Scotland often held by outsiders; for Mac, it’s a misty inconvenience. His first few days in town are spent at the inn attempting to negotiate the sale. As time passes and Mac becomes used to the town and its residents, he becomes emotionally enveloped by Ferness. The process unfolds beautifully throughout Local Hero, first through acclimation to the town’s minutiae—from Scottish pronunciations to local customs and spending time with the towns’ quirky residents. Ultimately, it’s the town and its surrounding areas that seals Mac’s infatuation. Forsyth and cinematographer Chris Menges often let the landscape speak for itself, starting with the sandy white beaches in the daytime. Figures become silhouettes against the pastel dusk. When Mac gazes into the midnight sky for the first time, he is struck by its beauty, a sheet of blue midnight filled with twinkling stars.

The land is still majestic, but modern life is so different from those Kailyardic days, and Forsyth’s juxtaposition heightens the film’s comedy and drama. The town’s residents are more than willing to sell off their land for a hefty payoff. Financial success informs the decisions made by Mac, Happer, and the residents of the town throughout Local Hero, yet it never leads to emotional fulfillment; we see that wealth is what hardened Mac and left Happer disinterested in anything beyond celestial recognition. Even when the sale of the town’s about to occur, one local expresses his regret: “I thought all this money would make me feel… different. All it’s done is make me feel depressed. I don’t feel any different!”

If the film had a more self-righteous approach, it might take the form of an antagonistic villager pleading against the sale of the town. The closest to this is Ben (Fulton Mackay), an eccentric hermit who owns the beach due to an archaic grant from the Lord of the Isles. Living in a shack made of beachcombing refuse, his unwillingness to sell isn’t from resentment, but rather a matter-of-fact sense of the true value of the land and the stars above. Mac tries to buy the beach for an enormous amount but Ben refuses, much to the town’s chagrin. As the conflict is about to come to a head, Happer suddenly arrives in Ferness and speaks with Ben alone. This conversation leads Happer to have a sudden change of heart, pivoting to building out Ferness as a research hub in order to preserve the local environment and further research the sky above.

With Happer satisfied, he sends Mac back to America to finalize the deal. Mac’s entire purpose in Ferness isn’t only upended, but at odds with his affection for the town. Back in Houston, all that remains of his trip are the seashell keepsakes and Polaroids—small tokens of memory instead of the peaceful life he once briefly imagined. As the Mark Knopfler score builds with overlapping synthesizer lines and guitar playing, Mac gazes out at the Houston skyline, a humming electric blue that surely feels like a cosmic taunt. Half a world away, the phone rings in the only phone box in Ferness—a long-distance plea for connection.

Fantasies, everyday desires, and personal obstacles permeate Bill Forsyth’s entire filmography. As he put it: “Thinking back on it, I think basically I've just made the same movie over and over again… in the sense that there's a main character who sets out with a kind of story in mind and really nothing happens to the story. But a lot, maybe other things, happen to the characters.” Forsyth finds humanity in the mundanity and irony of everyday life.