I’d at least heard of most of the films in the 1970s science-fiction collection the Criterion Channel streamed in January, but 1974's The Terminal Man was an intriguing unknown. It had a promising pedigree: based on a Michael Crichton novel, it was directed by Mike Hodges, probably best known for The Italian Job. That’s widely considered one of the best British movies ever made. The Terminal Man has not reached that level of acclaim, and it’s not hard to see why.

It’s the story of Harry Benson (George Segal), a man prone to a peculiar kind of epilepsy in which seizures drive him to rage and violence. Luckily, medical science has now come up with a neurological implant that can release a counter-shock in his brain and quell the seizures. Unluckily, his brain decides it likes the counter-shocks and starts triggering seizures to provoke them, leading to a worst-of-both-worlds mix in which Harry retains his conscious intelligence while also being driven to kill.

It’s barely science fiction, but you can see elements of a good thriller. Harry’s psychiatrist, Janet Ross (Joan Hackett), figures out what’s happening to him. He escapes the hospital nevertheless. Then for much of the second half of the film we follow him and Janet, as he’s driven to seek her out and murder her. There’s an argument to be made that Janet’s the main character of the film, as Harry’s driven less by character than by physiology—making this the only film in Criterion’s 18-film science-fiction collection with a woman as lead.

Unfortunately, the thriller aspect never really kicks into gear. The plot suggests that’s what it should be: at its core this is a story about a homicidal monster created by scientists who meddled where they shouldn’t have. But the movie takes too long to develop to that point. Much of the first half is given over to explaining Harry’s situation and setting up secondary characters.

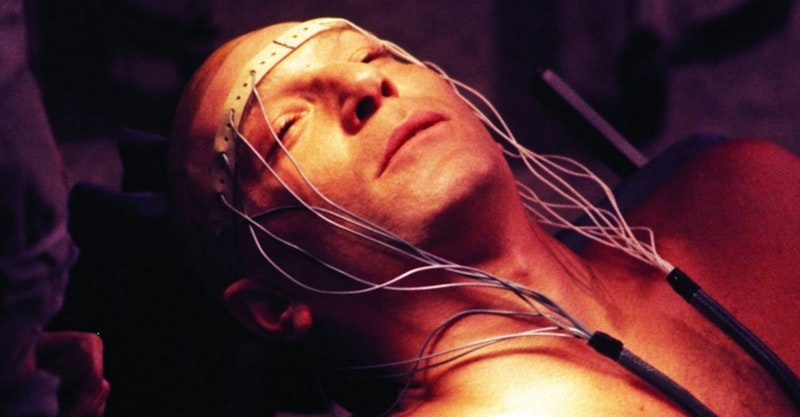

Notably, the actual operation in which Harry receives his implant is shown in a sequence of more than 20 minutes, with minimal dramatic tension—you know the operation’s going to work, because there’s no movie if it goes wrong. I’ve seen some people talk about the subdued use of color and technical achievement of the sequence, but to my eye it’s smooth and professional without being particularly appealing.

Theoretically, I think, the sequence is meant to display the character interplay among the doctors and Janet Ross. The problem is the interplay’s far too muted to be engaging. That’s also generally true of the character work in the first half or two-thirds of the film; it’s really not until Harry starts killing people that you get a sense of dramatic action. This approach could’ve worked as a slow burn, but fails because the characters are barely differentiated and there isn’t any effective foreshadowing of Harry’s fate.

Hodges has apparently said that he wanted to make the movie in black and white but was overruled; instead we get a palette of dulled colors that perhaps reflect the dulled emotional states of the characters. He’s also been quoted as saying he wanted to capture a sense of urban alienation in the movie, and that doesn’t come across at all—these characters exist within a web of relationships, and many of them have jobs in the large institution of a hospital. The alienation of an individual within an institution would be a useful theme, but the movie’s not interested in exploring it.

Nor does it seem interested in exploring anything else. Crichton’s fear of science undermining humanity comes through, but not with any depth or power. The core idea of behavior modification through technology is vaguely similar to A Clockwork Orange, but this film feels nothing like that one in terms of how it imagines the science. Time having passed, Crichton’s use of brain implants as a symbol of dehumanization and encroachment on human individuality is dated; brain implants have been used to stop epileptic seizures with some success and zero reported murders.

Still, the theme of human free will surrendered to technology hasn’t lost any power in the past few decades. It should be strong enough to carry the film. It isn’t. In part that may be because what seemed like new and threatening technology in 1974 now seems quaint; it becomes difficult to feel the way 1970s audiences might’ve felt at the sight of now-archaic computers. But that aside, the battle of technology and humanity doesn’t emerge dramatically.

The movie could also have tried to talk about free will, and whether biology is literally destiny. If Harry does things he doesn’t want to do because of his brain’s makeup, what does that say about the nature of human personality and neurochemistry? In the case of this movie, nothing in particular.

The Terminal Man is far better than it should be. It’s a movie with no dramatic tension, underwritten characters, no clear theme, and cinematography that’s only intermittently interesting. And yet it’s watchable. Hodges is too talented a director to make a bad movie. He just gave it a good try.