This is part of a series on Blumhouse horror films. The last entry on The Lazarus Effect is here.)

The best Blumhouse films use horror to ooze into the orifices of their own thematic and stylistic interests. Less successful efforts don't infest their genre, but are infested by it, lurching down the same ruts as ever, towards the same predictable ends.

Viral, a 2016 direct to video zombie exercise, falls into the second category—though, unusually, the genre it follows too slavishly isn't horror. Directors Ariel Schulman and Henry Joost start out using their disease apocalypse narrative to tell a young adult story about coming of age and sisterhood, mashing up feminism, John Hughes coming-of-age comedy, and Cronenberg body horror into a unique bloody effusion. There's a lot of potential, but most of it’s wasted as their narrative gets bitten by its own Hollywood tropes, and transforms into the usual shuffling corpse.

That narrative focuses on good girl Emma (Sofia Black-D'Elia) and rebel older sister Stacey (Analeigh Tipton), who have moved from Berkeley to suburban California. Their parents are having marital difficulties, and the father, biology teacher Michael (Michael Drakeford), is caring for them on his own, at least temporarily. Meanwhile, a mysterious infection is spreading across the U.S. Wormlike parasites grow in human bodies, and eventually take them over, forcing humans to attack and vomit blood to pass on the disease. Michael leaves to try to get mom from the airport, and is trapped by quarantine, leaving the girls to fend for themselves as the situation disintegrates.

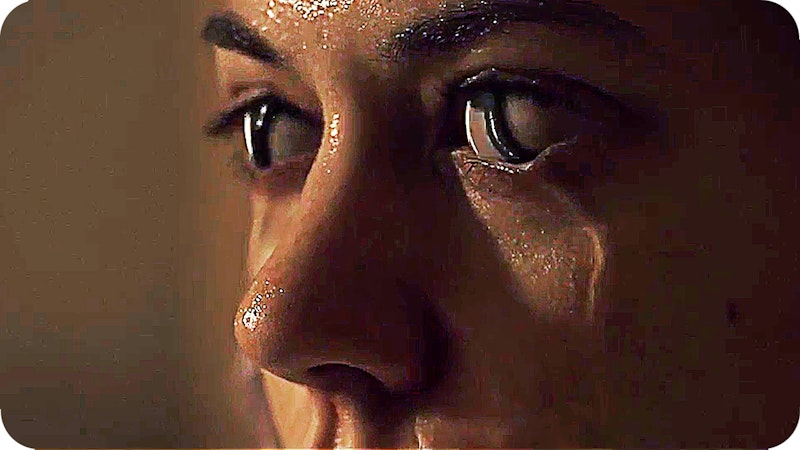

The movie is at its best when it connects its body horror to adolescent discomfort with burgeoning sexuality. The first frames of the film are close-ups of a high school couple kissing messily in the hallway, as Emma looks on with discomfort and fascination. Soon afterwards, she gives a tampon to her sister in the bathroom, and then flinches away when Stacey pats her on the head with the hand she used to insert it.

Bodies are gross, bloody bags, with minds of their own, and sex is a distasteful mess. Michael, it turns out, cheated on their mother with a grad student. Stacey discovered them, as she later discovers her own boyfriend CJ (Machine Gun Kell) cheating on her. The movie is half ready to embrace a female-centered version of Cronenberg's Shivers, in which lust is a zombie disease spread by nightmare mottled phallic worms, and sex is the apocalypse.

Against that apocalypse, Stacey and Emma turn to each other. The zombie crisis brings the two closer together, and the emotional center of the film is Emma's refusal to abandon Stacey when the latter becomes infected, even after Stacey (in a nifty bit of revenge) eats off her cheating boyfriend's arm. Emma uses dad's biological knowledge to operate on Stacey, forcing the worm that infects her to slide out of the back of her neck, where Stacey herself grabs hold of it and pulls it out, shrieking horrifically. Sisterhood defeats appetite, for food, sex, and blood.

But the film isn't willing to pursue either its loathing of bodies or its faith in sisterhood. Instead, the complicated sister/sister dynamic is inhabited, and then taken over, by a more expected boyfriend/girlfriend relationship. Emma falls in love with next-door neighbor Evan (Travis Trope), who is nice, supportive, and never infected with creepy bloody rage worms. Their romance is untrammeled, sweet, redemptive, and completely uninteresting.

Yet the movie goes out of its way to prioritize the dull romance. The terrifying and disgusting cure of Stacey, in which she saves herself with her sister's help, is the real emotional center of the film. But it's just discarded. Stacey relapses without any build-up or explanation, and Emma anti-climactically and with little fanfare shoots her in the face. The film's fear of sexuality and bodies is casually swept away as Emma and Evan ride off into the sunset after declaring their undying gratitude and affection for one another. Healthy romance means casting aside your fear of bodies, and your female friendships.

The film might’ve been truer to itself had it allowed Stacey to recover, and infected the bland Evan, following through on its themes of betrayal, sexual disgust, and female solidarity. Or it could’ve infected Emma and Stacey together, and had them chase down Evan, united by slimy tendrils of love. But John Hughes spit his sunny discharge in Viral's open maw, and the film helplessly staggers towards that final Hollywood kiss, even if the entire rest of the movie insists that kisses are for the worms.