As one century slipped slowly into the next, old dogs of New Hollywood found themselves without jobs. While still celebrated today, John Carpenter, Paul Verhoeven, and Brian De Palma all haven’t made Hollywood studio movies in over 20 years. Carpenter essentially retired, directing just two films between 2001 and 2010, and none since; De Palma decamped for France after Mission to Mars flopped in 2000, and besides trying once more in America with The Black Dahlia in 2006, he’s made films in Europe intermittently since 2002; Verhoeven’s the only one who’s continued working regularly and to acclaim: after Hollow Man in 2000, he waited six years to start making movies in Europe again. He’s never come back, and his critical reputation has never been better. In the 1990s, he was one of Hollywood’s most infamous sickos—now, every film he makes competes for the Palme d’Or.

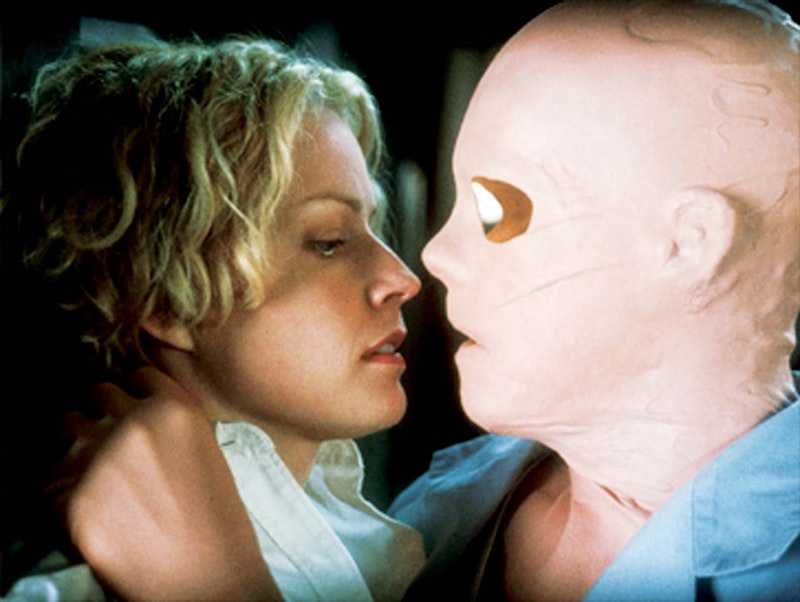

But Hollow Man didn’t bomb. It made $190 million against a $95 million budget, unlike De Palma’s similarly SFX leaden Mission to Mars from the same year, a much bigger movie that just didn’t have the money for its ambition. Mission to Mars is a space epic, while most of Hollow Man takes place in one location. Both films share distinct Y2K computer graphics, still primitive enough that they can be comfortably enjoyed now like rear projection or obvious matte paintings. All the lighting is high key and even to allow for special effects shots. Something as “simple” as Kevin Bacon’s insides rapidly becoming visible and invisible layer by layer had to be storyboarded out months in advance, with little room for adjustment.

It works if you like PlayStation 2 level special effects. Bacon’s transformations, along with all of the test animals he and his co-workers share in their silver future tube, aren’t what make Hollow Man interesting or drive the plot—it’s Bacon fondling, raping, and killing once he becomes invisible in this H. G. Wells’ story adapted for the new millennium. Verhoeven’s film remains visceral, with brutal head injuries and a decent amount of practical effects, while Mission to Mars shoots for the moon and lands on the sun; it’s also important to remember that making actors invisible wasn’t new in 2000: Woody Allen had Alice in 1990, and Carpenter himself had Memoirs of an Invisible Man two years later. The emphasis on the effects in Hollow Man is dated, but the rest of it is typically perverse and intense material for Verhoeven, one of his neglected films.

Not according to him. “I decided after Hollow Man, this is a movie, the first movie that I made that I thought I should not have made. It made money and this and that, but it really is not me anymore. I think many other people could have done that. I don't think many people could have made RoboCop that way, or either Starship Troopers. But Hollow Man, I thought there might have been 20 directors in Hollywood who could have done that. I felt depressed with myself after 2002.” De Palma’s foreign productions came and went without much notice, but Verhoeven’s most recent two, the rape-revenge thriller Elle and the lesbian nun drama Benedetta, have had modest success in American arthouses and major awards nominations.

What’s to be depressed about?

He can’t play with “the big toys” as Paul Schrader called the tools of a major motion picture in Hollywood: cranes, hundreds of extras, just as many on the crew. American directors who’ve reached a certain level of success will never go back to making shoestring $50,000 movies, as much as the public begs them: John Waters could’ve self-financed a sequel to Pink Flamingos, but why bother? He couldn’t do it at the scale of Serial Mom or Pecker—no one could. No one has $10 million to spare.

What’s depressing is how the economics that made Hollow Man such a “safe” movie have completely changed. Hollow Man is a step below every Hollywood Verhoeven movie besides Showgirls, but this was just something that was on the menu just about 23 years ago in America.

—Follow Nicky Smith on Twitter: @nickyotissmith