Starting with Criterion’s 2004 release of their John Cassavetes box set, the past five years have been good ones for the continued preservation of independent American movies. Milestone finally brought Charles Burnett’s astounding drama Killer of Sheep (1977) to DVD for the first time in 2007, and last year Burnett and writer Sherman Alexie helped bring Kent Mackenzie’s The Exiles (1961), about American Indians living in Los Angeles, back to theaters. Shadows, Cassavetes’ 1959 debut, set the artistic standard for these films: grainy black and white depictions of the urban underclasses, plenty of period music, and mostly improvised dialogue. Collectively, they give cinematic dignity to the forgotten residents of America’s movie towns, Los Angeles and New York.

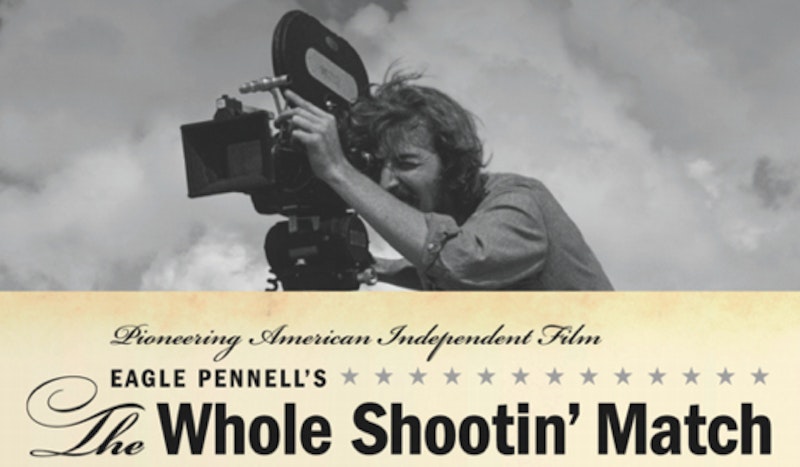

Eagle Pennell’s 1978 movie The Whole Shootin’ Match resembles each of the earlier films in various ways, particularly in how it reinvents, seemingly out of duct tape and 16mm film, another mythologized setting for American films. Shootin’ Match may be set in Austin, but this ain’t Hud or Giant, just as Shadows isn’t Miracle on 34th St. Both those earlier Texas-set films are mentioned by Pennell’s screenwriting partner Lin Sutherland in The King of Texas, a hagiographic but informative documentary on the director’s life and legacy that’s included in Watchmaker Films’ new deluxe edition of The Whole Shootin’ Match. And indeed, what you see in Pennell’s film isn’t exactly James Dean and Paul Newman: Sonny Davis and Lou Perryman, both enjoying their first feature film roles, play Frank and Loyd, friends and small business partners who can’t ever seem to make a big score despite Loyd’s eagle eye for get-rich-quick schemes. As the film opens, he’s trying to convince Frank to go 50-50 with him on a new polyurethane investment; Frank’s skeptical, since the two are still smarting from money recently lost on a chinchilla farm.

Loyd’s also an inventor, and he does eventually make a product that’s seductive enough to sell to a homewares company, but, like Shadows, The Exiles, and Killer of Sheep, The Whole Shootin’ Match is mainly a film about a specific milieu. It also happens, by nature of that milieu, to be funnier than any of those films. The wry humor of Loyd and Frank’s vernacular exchanges look forward to later American independent movies like Jim Jarmusch’s Stranger Than Paradise or Richard Linklater’s own Austin odyssey Slacker. Pennell’s obvious affection for his hometown slang (“If I’da wanted ta talk ta turds, I’da put a phone in the toilet,” a character says at one point) and the subtlety with which he lets his dialogue scenes play out anticipates the Tarantino of Pulp Fiction and the Coen Brothers’ Southern-set movies.

Doris Hargrave, who has one of the great female voices I’ve ever heard in a movie, is perfectly cast as Frank’s wife Paulette. She has three extended scenes of dialogue, including an immersive and deeply felt conversation with Frank at the drive-in movie theater, and another after he spends a night carousing and cheating on her. Neither of these scenes is particularly high drama, which is exactly the point; Shootin’ Match’s rawness and verisimilitude are such that we often feel voyeuristic, both to Frank’s tearful promises of self-improvement and the barely-spoken moments of humor that pass between them. This is how life is lived, in mid-70s rural Texas same as anywhere else.

Other moments linger just as powerfully, like Loyd’s boyishly excited face as he finally invents some kind of motorized bubble-blower, or a surprisingly surreal dream sequence where he correctly imagines the friends’ fate when dealing with big businessmen. The Whole Shootin’ Match is, like its predecessors, about dreams deferred, as well as the friends, family, and controlled substances we require to navigate those deferments.

The film’s characters drink more cheap canned beer than water, and Pennell himself was a notorious alcoholic. His career’s slow slide after The Last Shootin’ Match is detailed in The King of Texas, and it’s a painful story of unfulfilled promise and self-defeat. After Shootin’ Match’s surprise success (raves from The New York Times, a feature spot at the USA Film Festival in Dallas, and the oft-repeated claim that it inspired Robert Redford to found the Sundance Institute and festival), his drinking eventually claimed the friendships that brought that film to fruition. His 1983 film Last Night at the Alamo brought Perryman and Davis together again and occasioned its share of buzz, but Pennell’s career fizzled into the mid-90s, producing a number of films that many of his early friends admit to never even seeing. Watchmaker’s carefully curated collection of accompanying text is filled with recollections about Pennell’s drunken, abusive rants, his inability to keep money, his blinding benders. He died in 2002, a week before his 50th birthday, and no one who knew him was surprised.

But we have the films, including The Whole Shootin’ Match, which, while never as harrowing or emotionally intense as The Exiles or Killer of Sheep, has perhaps had a more recognizable stylistic influence on contemporary American filmmaking than either. Years later, it’s a reminder of how little money one actually needs to make a decent looking film—and how much compassion and creativity one needs to make a lasting work of art.

The Whole Shootin' Match, directed by Eagle Pennell. 1978, not rated, 108 minutes. 3-DVD set available from Watchmaker Films.