Cliff Robertson won the 1968 Best Actor Oscar for his role as a mentally disabled man in the film Charly. His triumph led to offers to star in films like Straw Dogs and Dirty Harry. He turned these down and instead wrote, directed and starred in an awful film called J.W. Coop (1972). Reflecting on this decision years later, Robertson said, “Nobody made more mediocre movies than I did. Nobody ever did such a wide variety of mediocrity.”

Robertson took supporting roles in studio films like Three Days of the Condor (1975) and Midway (1976). He then became immersed in a scandal that changed his life. In 1977, Robertson learned that a $10,000 check paid to him by Columbia Pictures for work he never performed had been forged and cashed by someone else. He reported the incident to the FBI who discovered the person perpetrating the forgery was studio head David Begelman.

The studio wanted to keep the incident out of the media. They quietly fired Begelman, claiming he suffered from “emotional problems.” They asked Robertson to remain silent on the matter. Robertson was indignant and spoke to the press. David McClintock reported on the story in his best-selling book Indecent Exposure (1982). Robertson’s whistle-blowing led to him being blacklisted in Hollywood.

Kirk Douglas wrote about the incident in his 1988 memoir The Ragman’s Son: “This is the town where Cliff Robertson exposed David Begelman as a forger and a thief, with the net result that Begelman got a standing ovation at a Hollywood restaurant, while Robertson was blacklisted for four years. On the bad days, you think of what Tallulah Bankhead said: ‘Who do I have to fuck to get out of this business?’”

In 1983, my father Igo Kantor, a film producer, optioned a script called Shaker Run. Written by Jim Kouf (who later wrote Rush Hour and National Treasure), the story’s a car chase romp about a stunt driver and his ace mechanic who team with a toxicologist to steal a lethal bio weapon from a government lab to keep it from the military. The script was B-Movie indie fodder, the type of film my dad excelled in making. In 1977, he made a well-received horror film starring William Shatner called Kingdom of the Spiders. The movie revived Shatner’s career. My father told me the secret of the film’s success. “Find a big name actor who’s fallen on hard times.”

My father contacted Robertson. Robertson connected to the Shaker Run story about a race car driver whose best days were behind him. They were hoping to recreate the 1970s box office magic of Smokey and the Bandit. My father raised funds and struck a tax-friendly deal with the New Zealand Film Commission. These were the days before Peter Jackson and Taika Waititi put the country’s film industry on the map. Production began in 1984. Bruce Morrison, a young New Zealand artiste known for music videos, was hired as director. The cast included ex-heartthrob Leif Garrett as Robertson’s sidekick. Lisa Harrow, a respected New Zealand actress, played the doctor.

I was out of college and given a job as Third Assistant Director. My duties were keeping track of SAG actor hours, creating call sheets and coordinating crowd control. Since we filmed in the sparsely-populated South Island, there wasn’t much crowd to control. I spent much of my time herding sheep away from the set. I brought the book Indecent Exposure with me, excited to discuss it with Robertson. My dad said the actor didn’t want to talk about his past. “His agent made it clear that no one is to ask Cliff about Begelman or Columbia Pictures.” This was a bummer, but I understood. The scandal transformed Robertson from an A-List actor into a B-Movie hack. My dad told me not to feel too bad for him. “He’s married to Dina Merrill, heir to the Post Cereal fortune. They’re one of the richest couples in America. That’s why he agreed to my movie for so little money.”

The night before production, the cast and crew met for a soiree at the restaurant in the hotel where we were staying. The gathering was casual but Robertson arrived in a formal suit and tie. Producer Larry Paar gathered everyone in a “circle of trust” to build camaraderie. He passed around bottles of Speight’s, New Zealand’s most popular beer. Robertson politely refused, opting instead for water. This was a blunder. The local crew immediately deemed the actor a prima donna and “first-class wanker.”

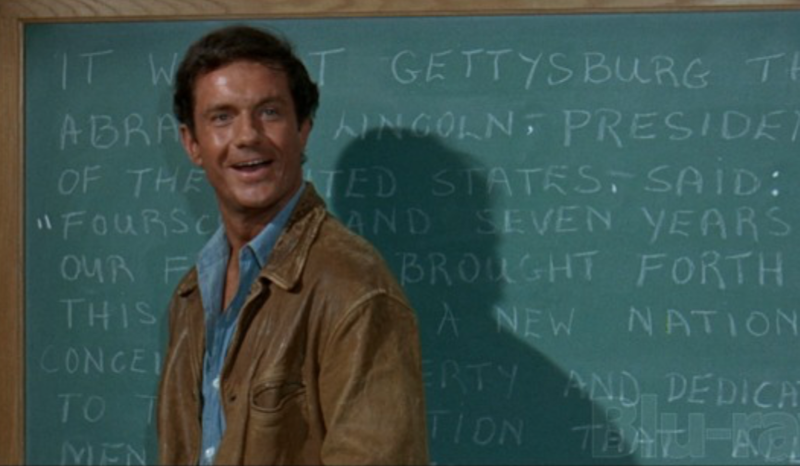

Day One of production took place at a Dunedin auto raceway. It was an icy-cold morning and Robertson arrived around seven. I introduced myself, telling him I was a big fan and that Charley was one of my favorite movies. I led him to the makeup trailer and brought him breakfast. He looked older than 61. He had ultra-tan leathery skin, thinning gray hair and his face was covered with liver spots. When he emerged from makeup, his hair was dark and full as if he were 30 years younger. Makeup Artist Amanda Butler had fitted him with a toupee.

Robertson’s first scene involved driving his character’s pink Trans Am race car on the track when the engine suddenly dies. He did a few trial runs and then indicated he was ready for the first take. The director yelled action, Robertson hit the gas then on cue the car came to a stop. The camera continued rolling as Robertson pulled himself from the driver side window (like all race cars the doors didn’t open). In the process, he knocked his toupee askew. He walked toward camera, unaware his hair piece was flopping across his scalp.

The director yelled cut and the entire crew broke into hysterics. Robertson didn’t know the reason for the laughter until the makeup artist appeared and fixed the toupee. He stormed off the set, hid out in his trailer, thoroughly humiliated, refusing to continue filming. My father called Robertson’s agent in Los Angeles and offer a profound apology. The damage was done. Robertson and the New Zealand crew would be at odds the rest of the shoot.

On the third day of production, the catering department passed around a basket of passion fruit. I’d never seen this food before. It was like a purple Hacky Sack with a wrinkled surface. One of the grips showed me the proper way to eat it. You bite through the rind and suck out the tart juice, swallowing the seeds. It was messy but delicious. Someone offered a passion fruit to Robertson who used a spoon to break the rind and dip into the seeds. When the New Zealand crew saw his bourgeois technique, they dubbed him an “American poofter.”

In private, I told my father the crew viewed Robertson as an entitled snob who thought himself better than everyone else. My dad reminded me that Robertson might be wary of making movies again given his recent past. I became Robertson’s advocate, telling the crew about the scandal and how the actor was unfairly punished for exposing Hollywood corruption. The crew didn’t care. New Zealand had socialist leanings and the locals perceived Robertson as a capitalist jerk.

The internecine conflict came to a head. We were in sheep country south of Christchurch, far from any major city. The script called for a gunfight between the heroes and the villains. In the scene, Robertson’s shot in the abdomen and loses a lot of blood. Just before shooting, the prop man summoned me. He confessed he had no fake blood for the scene. But he had an idea for a solution.

We grabbed two heavy steel milk jugs and walked across a sheep pasture to a nearby farm. The prop man offered the farmer $500 for one of his sick sheep. The farmer led the animal behind a barn then slit its neck. We filled the jugs with fresh sheep blood. It smelled awful. We returned to the set and the prop man sprinkled a few drops of cologne into the mixture and diluted it with milk. He filled several squibs with the concoction and fastened them to Robertson’s abdomen.

The shot came off brilliantly with the squibs exploding on cue. Some of the blood splattered on Robertson’s face. He grimaced at the nasty smell and then touched the blood mixture on his wardrobe.

“Why is it warm,” he asked. The prop man said they had to heat the mixture so it wouldn’t freeze in the cold weather. I could see Robertson was miserable. I’d read in his press clippings that he was an avid pilot who’d served as a Merchant Marine during WWII. On my day off, I went to a bookstore and bought him a copy of Tom Wolfe’s The Right Stuff. He was touched and thanked me for the gift, telling me he’d played astronaut Buzz Aldrin in the 1976 television movie Return to Earth. I hoped this might kindle a budding friendship but he remained aloof.

One night, the crew threw a party to watch the New Zealand rock band Split Enz perform on the American television show Solid Gold. New Zealanders had a bit of an inferiority complex. They hated it when people viewed their country as part of Australia. With Split Enz performing on a world stage, the Kiwis were excited to see their country acknowledged. We gathered around the hotel TV set. Even Robertson was present to show solidarity. The show host Marilyn McCoo addressed the TV camera and said, “Ladies and gentlemen, please welcome Australia’s hottest new band Split Enz.” Everyone in the room groaned, except Robertson who found the moment hilarious. He laughed at the crew’s distress. I laughed as well. That’s the moment I joined Robertson on the wanker list.

The following week, actor Sam Neill appeared on set to visit actress Lisa Harrow with whom he was raising a son. Neill’s career was just taking off with several New Zealand movies and roles on Australian television shows. (Jurassic Park would later make him a star.) Neill joined Robertson and Harrow for a friendly on-set lunch. That’s when the New Zealand crew went to work. They treated Neill as if he were Elvis Presley, requesting autographs and asking him to pose for photos. They ignored Robertson. The ploy worked as Robertson returned to his trailer and wouldn’t come out until Neill left.

Director Bruce Morrison did his best to keep in Robertson’s good graces. He consulted the actor for shot selection and blocking advice. He allowed Robertson to change dialogue on the set, engendering ill will from other actors. The detente collapsed once production moved to Wellington on the North Island. Someone defaced Robertson’s director chair changing the name to “Wanker-Son.” Morrison noticed and for a nearly imperceptible nanosecond betrayed a smile. He quickly regained his composure but it was too late. Robertson had seen his initial reaction. From that point on, Robertson disconnected from the film for good. He refused to accept direction from Morrison and only allowed one or two takes per setup.

Morrison complained to my father. Robertson froze out the producers telling them to discuss production issues with his agent. Robertson’s agent pulled the “he’s an Oscar-Winning actor” card, blaming Morrison who was directing his first major film. Watching dailies, it was clear Robertson was mailing in his performance. It didn’t help that he had little on-screen chemistry with co-stars Leif Garrett and Lisa Harrow. As we hit the halfway point, everyone just wanted it to be over. The resulting film was awful. For Robertson it served its purpose as a cinematic reclamation project. Shaker Run was his first starring role since the Columbia Pictures scandal.

Robertson rebuilt his career. His nemesis, former studio head David Begelman, was convicted for grand theft and fined $5000. He never went to jail though he did have his $1.4 million in Columbia stock options taken away. In 1981, Begelman was appointed chairman and CEO of United Artists. After a year of lackluster movies, he was fired. He subsequently founded Gladden Entertainment and released films like Weekend at Bernie’s and The Fabulous Baker Boys. Gladden went bankrupt in 1993. Depressed over his failures and declining reputation, Begelman died by suicide at age 73 in 1995.

Robertson’s career rebounded after Shaker Run and he became a working actor again. In 1996, he played the president in John Carpenter’s Escape From LA. In the early-2000s, he played Uncle Ben in Sam Raimi’s Spider-Man. His last acting role was in Spider-Man 3 in 2007. He wrote on his website, “Since Spider-Man 1 and 2, I seem to have a whole new generation of fans. That in itself is a fine residual.”

Robertson co-founded the Young Eagles aviation program in 1992, teaching youth about the history of flight. On the morning of 9/11, Robertson flew a private Beechcraft Baron plane over New York City to celebrate his 78th birthday. He was directly above the World Trade Center at 7500 feet when the first building was hit. Air traffic control instructed him to land at the nearest airport after all civilian and commercial aircraft were grounded. Robertson died in 2011 one day after his 88th birthday.