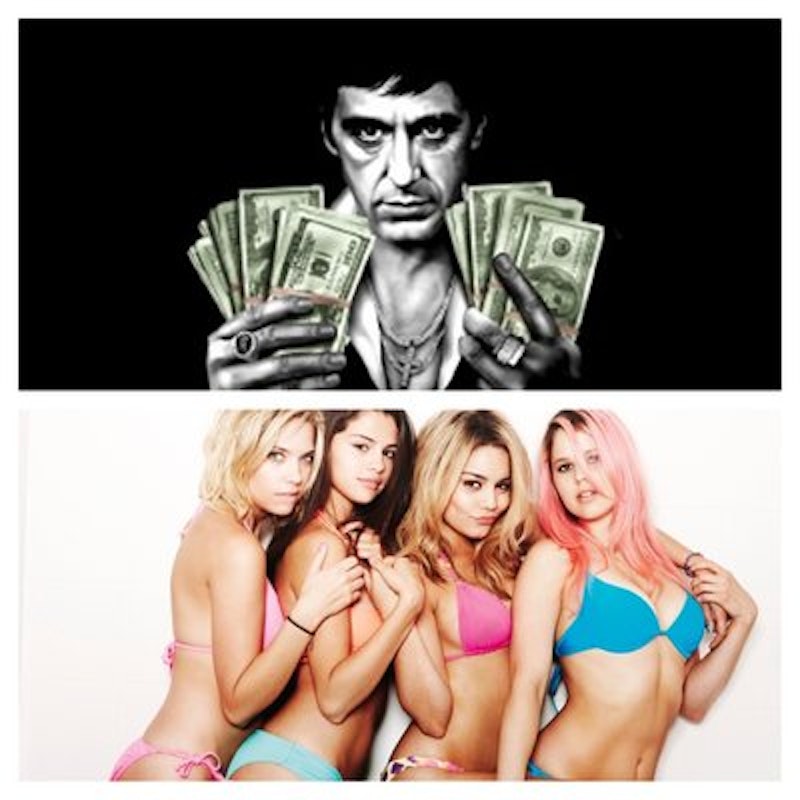

You know the story of Scarface: a poor Cuban immigrant, Tony Montana, kills his way to the top of Miami’s cocaine trade. He gets addicted to his own product, realizes that the American dream is grotesquely empty, and is finally shot to death in his mansion. Scarface is, in some ways, about the desperation that social inequality creates. Harmony Korine’s Spring Breakers is an inverse of Scarface—a depiction of the violent desire to remain in a position of privilege.

Harmony Korine is a weird dude. He began unsettling audiences when he wrote Kids back in 1995. He was 19. Two years later, he followed up with the absurdist take on rural America that is Gummo, his directorial debut. With Gummo, Korine trademarked his mix of documentary-type footage—such as clips of store clerks and other people in public that didn’t know they were being filmed—disorienting jump cuts, and bizarre characters. He further honed this pseudo-documentary style in Julien Donkey Boy, a claustrophobic journey into the world of a schizophrenic boy from New Jersey. Korine stepped away from his raw, shot-on-a-handheld style with Mister Lonely—a non-linear movie about an island inhabited by celebrity impersonators—only to return with Trash Humpers, an unsettling take on the type of nihilism popularized by Jackass.

When I watched the trailer for Spring Breakers, I was surprised to see that Korine directed it. But, despite the fact that the movie might initially seem like another empty action flick that’s mostly about badass guns, explosions, and t&a, Korine’s mainstream debut is laced with the type of social commentary that I’ve come to love about his films.

In one of the opening scenes, two white co-eds, Candy (Vanessa Hudgens) and Brit (Ashley Benson), sit in a classroom, ignoring a lecture about reconstruction in the South. They pass notes to each other that say, “I Want Penis” inside a heart, and “Spring Break Bitch” on a drawing of an erect cock. Instead of learning about some of the roots of American racial injustice, these girls are more concerned with trying to find ways to engage in the mindless fun that privilege can provide.

Brit, Candy, and their two friends, Faith (Selena Gomez) and Cotty (Rachel Korine), really want to go to Miami for spring break, but none of their parents or grandparents will give them money. So Brit and Candy decide to rob a fast food joint. They come up with the idea while taking bong hits, convincing themselves that “It’ll be just like a video game.”

While Cotty sits in a small pickup, waiting to make a getaway, Brit and Candy go into a fast food restaurant wearing ski masks and armed with water guns that look real enough. Despite Brit and Candy’s violent threats to customers and employees, which they begin yelling as soon as they walk through the doors, a black man stares at Candy, not wanting to give up his money. Candy puts her water gun to the man’s head, screaming that she’ll kill him if he doesn’t comply. The white girls steal enough money from the restaurant and its customers—mostly blacks and Latinos—to get to Miami, where, with Cotty and Faith, they party as if they were being filmed by an MTV camera crew.

After a few days, the quartet ends up at a party thrown by some local coke dealers, where they get arrested. Unsure about how to get bail money, Faith seriously considers calling her parents. Luckily, Alien (James Franco), an awful white rapper/drug dealer with long braids, lots of tats, and a silver grill shows up at the girls’ hearing and bails them out. This is one of several points in the movie when the plot feels ridiculously convenient, but I wasn’t bothered by it. Maybe I’m too much of a Harmony Korine fanboy to give an objective review, but, from fairly early on in the film, I understood that Korine is less concerned with creating a realistic plot than he is with making a statement about what people are willing to do to maintain social advantage.

The girls accompany Alien to one of his hangouts: a dingy pool hall in a black neighborhood. Although they’ve been partying with shit-faced frat boys who always seem like they’re on the verge of committing rape, this is the first time any of the girls show signs of discomfort. A room of black men stare at the white girls, who are all wearing bikinis. Faith didn't seem to mind getting ogled by horny white dudes, but she decides that something isn’t right with Alien. She calls her parents, who buy her a bus ticket back to her college town.

Despite this moment of blatant racism, Faith turns out to be right—Alien is a shady motherfucker. But Faith was also the only girl in their crew who seemed to have a conscience. Alien takes Candy, Brit, and Cotty to his house, which overlooks the ocean. He shows them all of his shit—throughout the scene, he keeps saying, “Look at all my shit”—which includes a wall of swords, several guns, and a lot of drugs. He tells the girls that he knew there was “something special” about them when he saw them in the courtroom, and, together, they start robbing college students who came to Miami for spring break. All of the girls seem to be naturally talented at taking things from other people.

The movie’s racial commentary picks back up at a strip club, where Alien runs into his former mentor, Big Arch (Gucci Mane), a mean-looking black dude with a teardrop tattoo below his right eye. He tells Alien to stop stealing his business, and the two gangsters agree to disagree. Alien has stolen his look, music, and speech patterns from black people, but he’s not content. He wants Big Arch’s drug empire.

Driving with the girls a few days later, Alien sees Big Arch and one of his cronies. The crony shoots Alien’s car, hitting Cotty in the arm. The large hole in her flesh tells her that she should return to her comfortable college life, and she calls her parents, who buy her a bus ticket. But Brit and Candy are still completely onboard with this violent lifestyle. Throughout the movie, their motivating goal seems to be avoiding the real world. They’d rather kill and/or die than grow up.

After Cotty gets shot, Alien, Brit, and Candy decide to make a move on Big Arch. Brit and Candy are the opposite of Tony Montana in that they were born into privilege and have access to things like higher education. When they make the move on Big Arch’s mansion, it’s a choice, whereas Tony Montana is forced to defend his mansion at the end of Scarface.

The trio kills their way through some of the many goons—all black men—protecting Big Arch’s waterfront property. Alien gets shot and dies, but Brit and Candy seem invincible. The mansion, with its lavish garden, ponds, fountains, and stone bridges, looks eerily similar to Tony Montana’s. Waves of black guys are gunned down by the two co-eds. They murder their way into Big Arch’s bedroom and execute the unarmed man in front of two women he’s been fucking. Brit and Candy effortlessly kill their way through a massive drug organization in Miami, and, unlike Montana, they make it out alive.

At the end of Scarface, I was left with this: although individuals from socially marginalized backgrounds can occasionally attain wealth in America through a combination of luck, intelligence, and hard work, this wealth can always be taken away; and the majority of the marginalized group will still be marginalized. What Spring Breakers told me: white people can easily steal from people of color who’ve risen above their socio-economic background. And they’ll still be white, which means that they don’t die at the end.

Follow @splicetoday on Twitter.