Plagues and epidemics were standard subject matter in the collection of dystopian 1970s science-fiction films the Criterion Channel streamed in January. One of those films struck me as especially interesting, in part because it was shot and set in my home city of Montreal. Two months ago, David Cronenberg’s 1975 feature debut Shivers was an intermittently interesting horror film with a few striking scenes. Now, waiting (as I write) for the coronavirus to strike Montreal with full strength, it’s a reminder of how hard it is to contain an epidemic.

Shivers takes place almost entirely in an apartment complex on an island in the Saint Lawrence River south of Montreal. Circumstances lead the apartment building’s resident doctor, Roger St. Luc (Paul Hampton) to learn that a mad scientist named Hobbes (Fred Doederlein) has created a parasite that’s reproducing and spreading through the complex like a plague. The parasite was designed to be medically useful, able to live in the human body as a substitute for a non-functioning organ—but was also to spur its hosts into orgiastic sexual excess. Hobbes believed that modern society had alienated humanity from its basic sexual identity, and the parasite was his attempt at a cure.

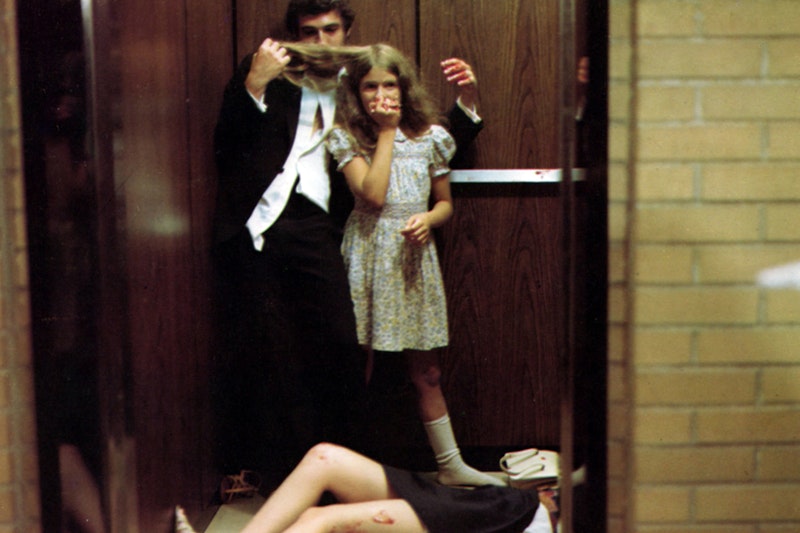

As the movie opens, Hobbes kills himself and the girl he’s used as a test subject, in a desperate attempt to stop the parasites from spreading. He fails, and through most of the film we follow St. Luc finding out the story of the parasites—mostly from Hobbes’ partner Rollo Linsky (Joe Silver)—while also following the spread of the parasite-plague through the apartment building. As night sets, St. Luc desperately tries to stop the epidemic and survive a building increasingly full of disease-ridden maniacs.

There’s gore and a lot of sex, and the two combine in disturbing ways. This is an early Cronenberg film, but it’s definitely a Cronenberg film. On its release it became the most profitable Canadian movie up to that time, but also spurred negative reviews, a debate in the Canadian Parliament, and a magazine article outraged at the use of a government subsidy to make the film—which led to Cronenberg’s eviction from his Toronto apartment.

It’s still shocking, if perhaps not to the extent it was in 1975. It’s not that Shivers is especially explicit. But it’s a distinctive mix of the visceral and the unsettling; it’s clinical in ways that you don’t expect.

It’s also not especially good. It looks cheap, grimy and washed out in a way that doesn’t help the story. The acting’s not strong, though Silver’s good in a minor role. And the plot doesn’t make much sense, going for shock value over coherency. The sex-mad plague victims have wildly varying intellectual capacities, with some cunning and others acting drunk or stoned. At the climax a line of plague victims walk sedately in a line together across a grassy lawn where it makes no particular sense for them to have gone in the first place.

Still, the structure of the story’s interesting. St. Luc gives us a central spine, someone who’s driving a narrative, but the heart of the film’s really in the connected vignettes of apartment dwellers slowly going mad as the parasite takes control of them. There’s a kind of character-based surrealism as people find themselves faced with loved ones acting in absurd ways.

This plays like what it is: a first work by a talented but inexperienced director. The story’s derivative of George Romero—not so much Night of the Living Dead but more The Crazies, another film about a disease that causes the afflicted to act out emotionally. But Shivers has moments of great power, individual scenes that pack an emotional punch. A scene between an afflicted husband and a wife desperately trying to stop his advances is particularly harrowing and effective; it’s drawn-out, in the sense that it doesn’t have a direct plot relevance, but it’s so emotionally powerful it’s narrative irrelevance actually emphasises its importance. We realize this is what the director cares about, not the plot mechanisms of how the parasites get from host to host.

There’s an attempt at developing a theme, about sexuality and repression and disease. Cronenberg’s love of body horror is present here, as we see parasites crawling under skin. More than grotesque effects, that’s the film’s overriding concern: the nature of the body. “Disease is the love of two alien kinds of creatures for each other,” a nurse says at one point; it’s an unexpected way to think about both love and disease.

(It also has an odd echo for a Canadian. Rainer Maria Rilke once wrote of “the love that consists of two solitudes which border, protect, and greet each other.” The phrase “two solitudes” was later used as the title of a novel by Canadian writer Hugh MacLennan, referring to French and English Canadians, and to this day “two solitudes” refers to the country’s linguistic division. Though set in Montreal, Shivers has very little French in it.)

The movie’s an artifact of an era when there was a gap between what adults understood about sex, and what could be said or shown on screen. More specifically, it’s an artifact of an era when that gap was narrowing by the moment. In 1975, nobody could’ve known how narrow that gap would shortly become. At the time the film was made, AIDS had not yet been clinically described. In retrospect, the parasite of Shivers is a kind of inversion of AIDS, a spur to sex instead of a reason to avoid it.

In March of 2020, another pandemic’s settling in. Social distancing is a common-sense precaution: one isolates oneself. The maniacal doctor of Shivers might see it as a denial of the sex urge. But there’s more at stake than the sexuality of one, two, or many people; life is on the line. Cronenberg’s film was not at all interested in the wide-scale effect of plague on society, only on the microcosm of the apartment complex. Life’s not as neatly metaphorical.