Earlier this week, I wrote about Greta Gerwig’s directorial debut Lady Bird, a very good coming-of-age story that was refreshing if not particularly innovative. For once we didn’t have to see through the eyes of the (male) director’s teenage stand-in and endure rants about how cool and ahead of their time they were. There were Sleater-Kinney and Bikini Kill posters in Lady Bird’s bedroom, but I didn’t catch that on first viewing.

Gerwig came to prominence as an actress about 10 years ago in indie movies like Baghead and Hannah Takes the Stairs, the former directed by Joe Swanberg, the latter by the Duplass Brothers, progenitors of the insidious “mumblecore” style that infected film festivals like a virus for the next six or seven years. I’d rather drink isopropyl alcohol than sit through Drinking Buddies again. These people had nothing to say and they decided to film it. But Gerwig was good. In 2010 she starred in Noah Baumbach’s Greenberg, and on the set, the two fell in love and have been together ever since, collaborating on Baumbach’s next two movies, 2012’s Frances Ha and 2015’s Mistress America. Both are awful, as I wrote on Monday—and I’d add that the precious aesthetics of Frances Ha, its high contrast black and white, and its suffocating Woody Allen cosplay would probably not fly today, even if it lacked the bright red flags of Louis C.K.’s very similar I Love You, Daddy.

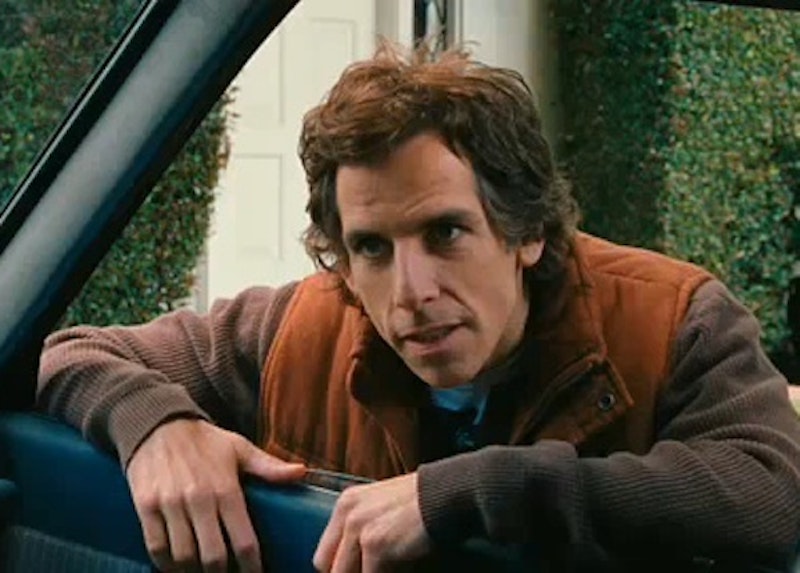

Consider watching Greenberg again, if you ever did. It bombed when it came out and Baumbach did a total 180 with his following films. But Greenberg stands alone in his otherwise irritating and anodyne body of work and from most major American movies in that its titular character is completely despicable. The Coen Brothers pulled the same move successfully with 2013’s Inside Llewyn Davis, but Roger Greenberg (Ben Stiller) is even more absurdly rude and repulsive, and the movie is excruciating to watch at times. His conversations with family members, strangers, and Florence (Gerwig) verge on the surreal, a man with no ability to pick up on social cues or any capacity for empathy or sincerity. It’s stunning—and no one knew what to make of it. Released in the spring of 2010, Greenberg has already dated in some ways: Gerwig’s character casually uses the word “retarded” as most people did seven years ago, and when Greenberg goes off on a rant at a bunch of young people at a party about how they’re too “confident and sincere,” it’s obvious he’s talking about Millennials, a generation that hadn’t been named and castigated yet.

Some setup: Florence works as a nanny and house sitter for a wealthy family in Los Angeles. The Greenbergs are about to go on a six-week vacation to Vietnam, and her boss tells her on their way out that his brother, Roger, is going to be staying at the house while they’re gone. “He just got out of the hospital, he had a nervous breakdown.” Roger Greenberg shows up and it’s immediately obvious that he’s a hapless prick.

Re-watching this in 2017, I was bracing myself for some kind of mental health revelation, because “hospital/nervous breakdown” could mean a lot of things. Is he on the autism spectrum? Certainly acts like it. Is he severely depressed or unstable? Well, he’s on Zoloft, but so is most of America, so no, Greenberg doesn’t get a pass. The Greenberg character is perhaps the most vivid excoriation of the aging Gen X hipster I’ve ever seen, and it makes Baumbach’s subsequent work all the more disappointing and confusing, because it’s as if he embraced the wack sensibilities of an effigy he completely torched in 2010.

Greenberg lives in New York and tells everyone he meets in L.A. that he doesn’t drive. When asked what he’s up to, he says he’s “just trying to do nothing for a while. Deliberately.” When Florence and Greenberg first meet, he makes fun of her taste in music, naïveté, habits and tics as a young person. They end up in bed somehow, but this isn’t typical wish fulfillment by an overly imaginative director: Greenberg is incompetent, insensitive, brutal and hard in a way that is actively repellent. He blows up even as she practically grovels at his feet: “I don't know! Anyone. I'm doing nothing, I'm not tied to anyone. How many times do we have to go over it. Jesus! I should be with a divorced 38-year-old who has teenage kids and low expectations about life. I don't wanna fucking do this anymore. God!”

He’s emotionally abusive, and when Florence is fed up with him, the absurdity of his character and the obvious parody accelerates into amazing uncharted territory: “I think you’re just like acting out some weird family dynamic, father issues. Were you molested as a child? I think you’re projecting and taking it out on me.” She drives away. This movie needs to be reconsidered, because it’s also a golden guide on toxic masculinity in people we don’t typically associate with that term.

His poor old friends have to suffer through his directionless rants about the state of the world and life in general, with one humoring him: “Youth is wasted on the young.” Greenberg replies: “I’d go further: ‘Life is wasted on people.’” This is all played deadpan, and I was howling watching this the other night, totally aghast and nonplussed by Baumbach’s dedication in skewering a very particular type of asshole, misogynist hipster that’s luckily dying out now: the type of guy that declined a four-album deal from a major label because he “didn’t want to deal with all that corporate shit,” a guy that does one line of coke and can’t stop changing the music at a party, going on and on about how Duran Duran is “great coke music!”

Greenberg is humiliated, emasculated, and invalidated throughout the movie, and for good reason: it’s a good thing his attitude has died out with the new sincerity of the Millennials and the rising Generation Z. No one should be judged or criticized for the music they like, the clothes they wear, or the lives they choose to lead. I suspect Greenberg bombed because no one likes a mirror held up to their face, and everyone else who’d never met a Greenberg—the lucky ones—just weren’t interested in sitting through an examination of a terminal loser’s life.

Greenberg’s an important film because it’s an evisceration of a very particularly type of Gen X hipster that is all too often exalted or excused in movies and in popular culture. John Cusack in High Fidelity is a great example; Robert Christgau (bomb!) is the Patron Saint of these people; and the early years of Pitchfork were defined by these snooty disciples of cool and received wisdom. Say the right things, dress a certain way, never admit to liking anything outside your pre-determined box. Greenberg is comparable to Peep Show, in that its ultimate message is that dumpy losers can be absolutely horrible, irredeemable people, too. It’s not just the CEO’s and the gropers put on “indefinite leave” these days. The rats that run through used record stores are slowly dying off, and the world is better for it.

—Follow Nicky Smith on Twitter: @MUGGER1992