I often find myself smugly outside of the zeitgeist, although from time to time I fall into trends too. In the summer of 2019 when I first moved to Baltimore, didn’t know anyone, didn’t have a job or really much to do, I found myself in a streaming service nest that for once had algorithmically aligned with something I was “interested” in: race cars. It was possible I was primed for this my whole life, watching Talladega Nights over and over again as a kid or my parents getting me Need for Speed instead of the more violent video games or the European car magazines my dad would bring back from endless business trips. Perhaps it was only a matter of time before I’d get myself into motorsports.

Like so many Americans, I was captivated by the first season of Netflix’s Drive to Survive, a documentary-ish series with the aim of revitalizing and expanding interest in Formula 1 after a monumental regime change during a global decline in viewership. It was popular, with the pandemic leading to tons of new eyes on the sport because of the show, and the 2021 world championship being one of the most contentious in history, with the god-like Sir Lewis Hamilton finally toppled by the young hot shot Max Verstappen, who has himself gone on to his own era of total domination (one which makes the races boring and I hope will weed out many of the bandwagoning fans). At the Canadian Grand Prix earlier this June, Verstappen got his 41st win making him the fifth most successful driver of all time, tied with the sport’s patron saint who died tragically at the age of 34. I thought it was finally time to cover a major blindspot and watch Senna.

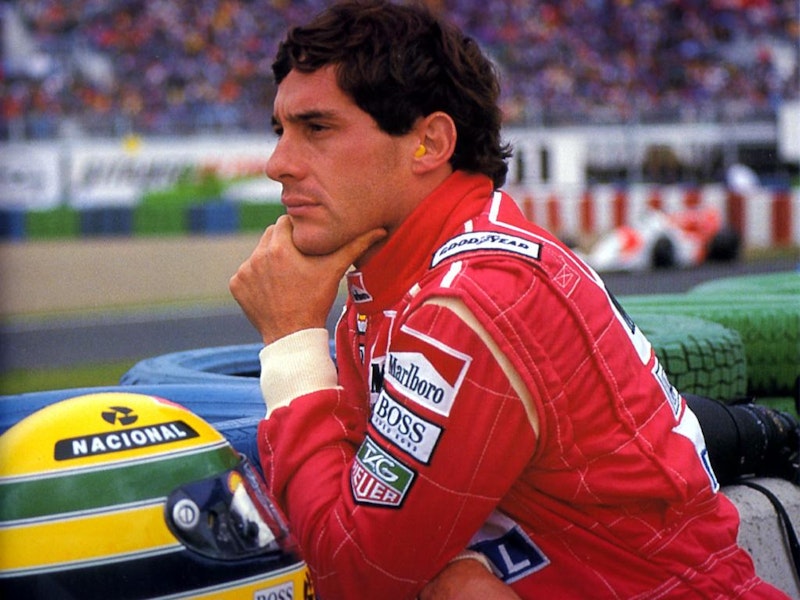

Ayrton Senna was born to a wealthy São Paulo family in 1960, and at a young age took an interest in go-karting, often competing and winning against kids that were years older than him. He moved to Europe at 18 to compete in the FIA’s Karting World Championship, something he’d later reflect on as “Pure driving, pure racing,” as opposed to the big money and politics that’s endemic to Formula 1. According to the film, Senna’s career is defined by two things: his rivalry with another all-time great, Alain Prost, and his untimely death at the San Marino GP in 1994. It weaves this narrative exclusively through archival footage and interviews overlaid on each other, creating a collage of found material that represents not just the reality of the time, but the way that reality was captured. It also creates a reality of its own.

Senna isn’t as much a sports documentary, but rather the veneration of a saint. The film shows Senna as a Bible-carrying golden boy who was too good for the world he lived in, hated by Prost and the FIA but loved by the people. This isn’t exactly true. There’s no question that Senna was a national hero to Brazil, the government declared three days of national mourning upon his death and around 200,000 saw his body lying in state São Paulo. But as a driver as opposed to a legend, he was still human, and his relationship with Alain Prost is more complicated and two-sided than the film presents in its simple heroes and villains narrative.

Prost was a fast driver who earned the nickname “the Professor” for his preternatural calculus on and off track. After a number of embarrassingly close title defeats, Prost made the realization that so many motorsport champions eventually make: you don’t have to lead every lap, win every race, drive the car 100 percent of the time—car racing is as much about management as it is driving fast. Albeit Prost took this management to an extreme, and his first famous crash with Senna at Suzuka came as a result of Prost slowing down in order for Senna to catch up with him, both so that he could maintain his tires and wear out Senna’s in the dirty air behind his car. Senna, all always drove the car at 100 percent, spotted a gap and dove in, sending them both into the gravel. At this point in the season, Senna had to win there in Japan and at the final race in Australia to clinch back the title from Prost. After the crash Prost was out but Senna was able to get his car back on track with assistance from the marshalls, going on a jaw-dropping drive to retake the lead and win the race. He was disqualified for missing a chicane when he re-entered the track, a ridiculous decision by the FIA and still controversial which resulted in Prost winning the title that day. Senna crashed out in the next race in Australia, so Prost would’ve won it anyway.

A year later at Suzuka was the most dramatic point in their rivalry, where the roles were reversed and Senna could’ve not even finished the race and still won the title. There was contention at the start where the FIA strangely changed the pole position, from which Senna was starting from, was moved off of the racing line to the dirty side of the track, giving more grip to the driver starting from P2 (Prost). It was another affront against him committed by FISA (the same thing as the modern FIA) president Jean-Marie Balestre, who Senna had blamed for his disqualification in the previous year’s Japanese GP in order to give a title to his fellow countryman, although Balestre wasn’t present when the stewards made the decision and Prost wasn’t actively using the FIA against Senna as the movie would suggest. It wasn’t all institutional advantage for Prost, either, as his “favoritism” when they both drove for McLaren was departmental—where the chassis of the car was designed more in Prost’s favor while the Honda powered engine better suited the driver that company had a long-standing relationship with, Ayrton Senna and his aggressive driving style.

What the movie also fails to mention is that their dramatic repeat crash in Suzuka was intentional; Senna decided to drive into Prost giving himself the title to get back at Balestre. It brings a different light to Senna’s most famous quote in an interview after the Grand Prix, “Being a racing driver means you are racing with other people and if you no longer go for a gap that exists you are no longer a racing driver.” If going for the gap that exists makes you a racing driver, then what does going for a gap that does not exist make you?

A part of me wishes I had seen Senna many, many years earlier. Perhaps if Ron Howard’s Rush was any good I would’ve moved on to this documentary and started my love of motorsport sooner, but getting obsessed with the real thing and then working my way backwards into some of its defining pieces of media makes my relationship with them very complicated. I remember a few years ago getting a new spark about the nature of sportswriting by watching Jon Bois’ documentary The Bob Emergency, where hard sets of data and information—win states, batting averages, even just the names of athletes—can be used as launching boards. From these objective truths we can extrapolate the subjective human truths as well. What I don’t like about Senna is that it takes objective information (archive footage) and mixes it with subjective muddling (editing, overlaid archive interviews) to create a hyperreal world with the illusion of a real one. This could be as little as the movie talking about the 1988 Monte Carlo GP while showing footage from 1990, or it could be as big as turning a story completely one-sided and unnecessarily conflating another driver with an organization that does operate like a real-life movie villain.

Senna producer James Gay-Reese took this approach to heart while overseeing Drive to Survive, expanding out little dramas or creating them out of whole cloth. It’s a struggle with spectacle that has trickled back into the sport itself, with race directors making often dangerous decisions to heighten the action, bringing back questions at the heart of sport about whether its appeal is that terrifyingly dangerous relationship between man and machine. Even through all the heroics and bravery, it was probably just a small part failure that caused Senna’s fatal accident. It was a random shunt of violence that made an already tragic weekend, with the death of Austrian driver Roland Ratzenburger the day before, even more unfortunately legendary. Senna, in all its manipulation, renders this devastating event with emotional gusto. It’s a moving sequence with the utmost respect for its subjects, it’s a moment where its emotional truth aligns the truth itself. I wish I could say the same for the rest of the film, which so often bends reality in favor of something less interesting.