Becoming a successful, professional artist isn’t just dependent on luck, talent, and timing. You have to start early and catch any wave that comes your way. Throughout film history, there are people on both sides of the camera that managed to stay relevant for several decades, despite changing trends: Joan Crawford, John Wayne, Meryl Streep, Martin Scorsese, Tom Cruise, Clint Eastwood, Quentin Tarantino, and Spike Lee come to mind; but with the exception of Crawford, all of them defined themselves early in their careers and rarely deviated from “themselves,” and when they did, they played it safe and succeeded. These people have made different kinds of movies, but they are all recognizably theirs—the persona outshines any contemporary influence on their work.

Other than the transition from silent to sound in the late-1920s and early-1930s, there was no more perilous period in Hollywood history than the 1960s, particularly for actors. The studio system was bloated and about to collapse, still signing young men and women to seven-year contracts and grooming them to be in-house talent. Despite Marlon Brando, James Dean, and Montgomery Clift’s influence on film acting throughout the 1950s and 1960s, studio movies hadn’t caught up, and they weren’t producing new stars. Paul Newman managed to escape, but he was older than Warren Beatty, who never would’ve reached the heights he did if not for Arthur Penn’s Bonnie and Clyde in 1967. He was a contract player, and hardly distinguished. He parlayed that success, along with a slew of roles in the 1970s, into an impressive career as a director. Today, he’s a living legend in Hollywood.

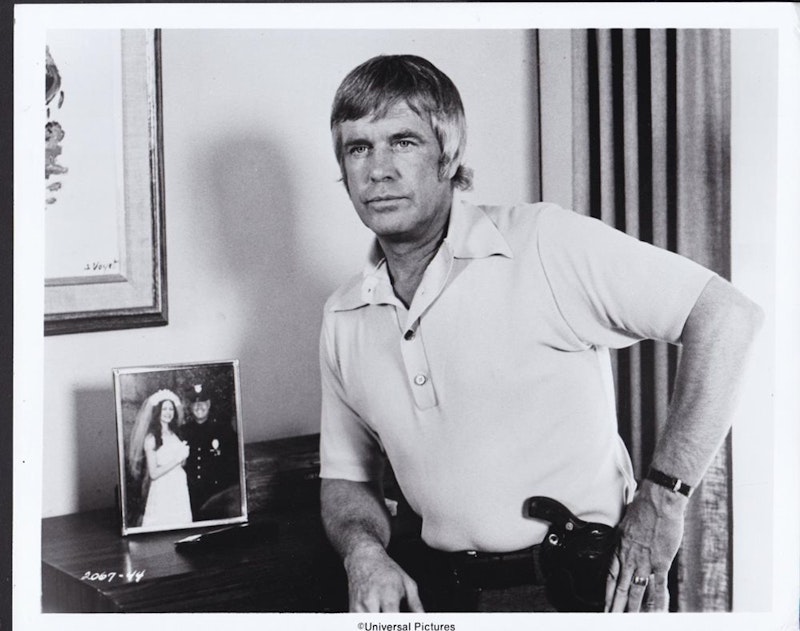

George Peppard, a contemporary of Beatty’s, died in 1994 at 65, long since relegated to television and gone from the movies he appeared in so often in the 1960s. He was unlucky enough to land his breakthrough role in 1961: opposite Audrey Hepburn in Breakfast at Tiffany’s, the only iconic film he ever appeared in. How the West Was Won, from the next year, is remembered for its title and its ultra-widescreen presentation; Home from the Hill, from 1960, may be the last Vincente Minnelli movie to turn a profit, but it’s an epic Western, and not particularly remarkable; others 1960s epics like The Carpetbaggers, The Victors, and The Blue Max carry no cultural resonance. By the end of the 1960s, Peppard started to settle for worse scripts and less cushy deals, leading to a run of genre films and B-movies through 1972, when he began working regularly in television again with the series Banacek.

Among the best films of this period in Peppard’s career are Pendulum, The Groundstar Conspiracy, Newman’s Law, Cannon for Cordoba, Rough Night in Jericho, and Tobruk. But measured against other American films of the late-1960s and early-1970s, they’re relics from a dead system, somehow still churning out product from beyond the grave. Plenty of actors foundered in this stuff, fun as it is, but what’s amusing about Peppard is how seriously he took himself and his work. His drinking got worse as the years went on and the scripts got worse still, yet even in the work he chose to do, there’s a fundamental lack of understanding and a miscalculation in every performance. Peppard plays these police procedurals and war movies with the stentorian authority of a hammy stage actor, never once becoming anything higher than an actor practicing his technique.

This kind of peacocking silliness is especially funny when he’s in these cheap genre movies, still playing with the intensity reserved for Tennessee Williams. By the time he started on The A-Team, Peppard basically left the movies and settled for what the rest of his life would look like, and where it would be: the boob tube. It’s no surprise Tarantino and Paul Thomas Anderson invoked him in Once Upon a Time in Hollywood and Licorice Pizza, respectively: Peppard is as much an artifact of that period as flower power and streakers.

—Follow Nicky Smith on Twitter: @nickyotissmith