At the Indie Spirit Awards on February 25th, the packed crowd of those supposedly on the film industry’s fringes sat silently in their tent as the sounds of protestors chanting “Free Palestine'' echoed through the curtained walls. This “independent” event is independent only in the sense that it’s not codified in its relation to studios—many of the films involved millions of dollars fronted by multi-billion dollar multinational corporations. Only a couple were willing to acknowledge what was happening without making a joke. One was the John Cassavetes Award winner (given out to films made for under $1 million) Babak Jalali, who couldn’t quite get the words to his speech out because he was so moved by the protestors.

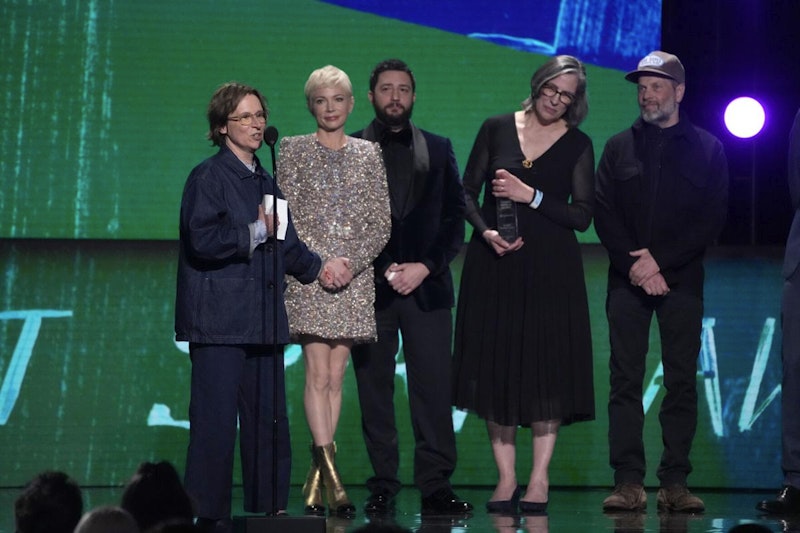

The other was Kelly Reichardt, upon the acceptance of her Robert Altman Award (ensemble) for Showing Up (2023). Reichardt ended her speech by noting that the last time she saw Altman was in 2003, and noted he was “pissed” about “America dropping bombs on Iraq” and she thought “that he would have a lot to say, just… this weirdness. Being here and celebrating each other and our work and also, you know, life goes on outside the tent. Peace.” It’s a confused, half-hearted statement that may or may not reflect Reichardt’s real feelings on the protests—she’s always seemed more comfortable behind a camera than in front of it. It stands in stark contrast to how earlier that the same day, 25-year-old active duty Air Force serviceman Aaron Bushnell self-immolated in front to the Israeli Embassy in DC in protest of the genocide in Gaza.

What’s become increasingly apparent over the last few years, and hyper-accelerated in the last few months, is the differing appetites for action between the now-aging Gen Xers and Millennials against an increasingly desperate Gen Z. In the 1990s, counter-culture was the culture, and the geopolitical issues of the day were apparently open for discussion after the Soviet Union collapsed and liberal hegemony took over. This new order was so quick it may have never really existed, with dreams of dissent in Russia slowly burned away after Yeltsin sent tanks to the (Russian) White House in ‘93 and W. Bush all but killed the illusion of free speech in America after 9/11. It’s not that rebellion (or the image of it) was no longer “cool” in the United States in the 2000s, it was practically non-existent in pop culture. There’re a few relics like the Dixie Chicks (taken off the air), Green Day (who hadn’t made a piece of punk since ‘94), and Michael Moore (booed at the Oscars for protesting Iraq) that stand as a testament to some kind of dissent within the jingoistic monoculture, but it also feels like a bad joke to rely on those for a political compass.

This is probably why some of the most interesting pieces of millennial art from the era aren’t surface-level satires like John Sayles’ Silver City (2004), but the works that strike at just precisely how politically impotent the era was. In my first piece for Splice Today, I argued that this is one of the interesting tendencies in Mumblecore—the between-the-lines quality that highlights Millennial impotence in matters social, sexual, political, etc. I’d also argue that that tendency towards impotence is in continuity with the people slightly older than them, who came of age into a world of dreams broken by the collapse of the 1990s, the same way Millennials' futures would be squandered by the Great Recession. The fate that befell Mark and Kurt in Old Joy (2006) was that of the entirety of Gen X: either become a suburbanite who listens to progressive talk radio from the careful confines of your car, or end up a listless wanderer constantly on the verge of total financial and spiritual desolation. The world around them isn’t static, it’s decaying, but they have no ability to affect its indifferent demise.

If there was one aspect of the culture that started to coalesce into specifically radical action in the 2000s and early-2010s, it was the environmental movement that was newly rejuvenated by nightmares of the apocalypse. Night Moves (2013) was Reichardt’s (as I said in my Paste writeup) psychological thriller about ecoterrorism, examining the external and internal pressure that emerging catastrophe was having, specifically on Millennials. What Reichardt shows us in her trio of terrorists is a conviction that’s rooted in action at the expense of theory; their resolve has to be unquestioning because when they do question it, they fall into psychological ruin. Taking cues from Dostoyevsky’s Demons and Bresson’s The Devil, Probably (1977), Night Moves presents a generation trapped within an unconscionable world that also, despite trying, moves with inevitability. Night Moves is a Gen Xer’s portrait of Millennials desperately trying to break the shackles of their own impotence.

The other great Gen X observer who was birthed out of 1990s independent film is Richard Linklater. His form, at first outright radical with his Benning-esque aspirations, and then with his Indywood courting (so typical of that decade's auteurs). Richard Brody made an interesting observation about Linklater’s Hometown Prison (2024), a feature-length documentary that was so quietly released as part of a three-part docu-series on Max, God Save Texas (2024), that, like The Film Stage’s Nick Newman, I had no idea this movie existed until Brody’s tweet about it ragging on The Zone of Interest (2023). Brody—in his sometimes enlightening, more often than not stupid contrarian form—went on to Tweet that The Zone of Interest is built like “a science-fiction film about the Holocaust,” complete with “world-building.” The Zone of Interest is replete with constructions: it’s a film of buildings, systems, routines. Even the making of the film, filled with hidden cameras and crewless sets which leave the actors to wander for the better part of an hour, implies that everything to it is an exercise, and that there’s something important to film as an exercise rather than just a medium of delivery.

Piecemeal, I’ve been making my way through Peter Watkins’ monumental 1987 documentary Resan (The Journey), a 25-and-a-half-hour magnus opus. It's a stunning switch from Watkins’ hybrid form, wherein his films give the appearance of television documentary, yet are historical recreations, often anachronistically, making it seem like a BBC crew was filming the last land battle in Britain in Culloden (1964), a dystopian fascist American near-future in Punishment Park (1971), or the chaotic days of the Parisian communards in his masterpiece La Commune (2000). In Resan, Watkins is ideological in his approach to documentary. In his journey around the world—exploring the way nuclear weapons have reshaped modernity, the economic engines of states, how the media manufactures consent for it all, and ultimately the effect this intensively constructed reality has on people—he interviews people from every social strata from every pocket of the earth, follows a Canadian TV crew around as they prepare for a meeting between Reagan and (the thankfully now, too, deceased) Mulroney, follows the veins of the nuclear weapons industry, and all the time criticizes his own form as much as anyone else’s he looks at. Anytime a piece of news footage is shown in Resan, Watkins and co. (as he tells us in narration early on in the film) will punctuate every cut, visual graphic, or other editorial decision made by the producers with a sound. It highlights, at every turn, all these images that we’re inundated with are chosen, organized, and presented with bias: they’re not just telling you a story, but building one.

Somewhere in that incredible runtime, there might be a snappy two-hour movie buried within Resan. One which has just the important statements from interviews, cleanly lays out the ways nuclear weapons travel, and expresses the terrifying idiocy of spending so much in the name of saving the world only to apparently inch it closer to the brink of destruction when, at the same time, there was already so much to fix, so much work to be done. But that approach would miss the purpose of Watkins’ exercise. It’s not just constantly iterative, but reiterative. At first it can seem ridiculous why Watkins keeps asking children from around the world “If they talk about this at school” after showing pictures of Hiroshima and Nagasaki victims to their family—why would a kid know about this? Well, why wouldn’t they? Why shouldn't they? There’s a seriousness to perspective, where the same information is presented to and the same questions are asked of people in urban France as rural Tahiti (and in this specific case, showing the Tahitians what the French, whom they are trying to break the colonial yoke of, discussed). Watkins is giving voice to varying degrees of “average” persons the gravitas of a camera, which mass media usually only does for experts or politicians. In doing so he reshapes the political reality of the world, revealing one intentionally concealed by the mainstream systems.

Linklater approaches his subjects with a similar seriousness, although it’d be disingenuous to refer to the people in front of Linklater’s camera as just subjects: they’re people, and, in the case of Hometown Prison, they’re more often than not people he has personal connections with. Linklater moseys around his hometown of Huntsville investigating the strange tension of his mostly benign childhood memories and the prison complexes that make up the town’s industry. Linklater, like Watkins, places an emphasis on the importance of the exercise itself. It’s important that Linklater physically returns to Huntsville, to the houses he grew up in, to the people he grew up around. It is partially an investigation of his own cinema, like what Davies and Maddin do with their homes in Of Time and the City (2008) and My Winnipeg (2007), with Linklater driving by locations that inspired Dazed and Confused (1993) or Everybody Wants Some!! (2016). But what makes Hometown Prison a potentially major work in Linklater’s filmography is direct address. It’s Linklater, perhaps for the first time, directly confronting his own experiences. Like Reichardt, he’s often more comfortable on the other side of the camera, and here he makes his memoir of Huntsville as much about all of its residents as he does himself—the community is, after all, one massive, messy web of connections. We get glimpses of lives like in Boyhood (2013), but instead of leaving the gaps open for speculation, Linklater later directly confronts the passage of time. The present tense, to Linklater, is made up of memory, built on all the years that came before it. And if this is the case, the way that incarceration aberrates time is an extreme violence that can’t be readily understood by those on the other side of a dichotomous world.

What makes Linklater such a deceptively smart filmmaker is the way his form reframes the content of his works. Not the exterior form—like the shots, editing, music, etc.—but the form behind the camera. It’s those nine-year gaps before each Before film that makes them so devastating, or the gradual aging of everyone in Boyhood that gives weight to its ostensibly banal story. Hometown Prison is the same, where the unending tragedy of the continued system of injustice that keeps propping up Huntsville economically is felt by Linklater opening with images he shot 20 years before, and not much has changed. It’s also this approach that also (usually) gets him less attention than something like The Zone of Interest, where the blatant form is more grabby, especially at a time when (as the filmmakers have pointed out) its use of perspective is so prescient in understanding the mentality behind the state of Israel’s fascist, genocidal war on Palestinians.

The exploratory forms that Linklater and Reichardt take on are probably the best types of artistic work that can come out of a politically impotent generation like the Xers. While they don’t offer a model to fix the world, they do provide heuristics for understanding it. It’s then, with those tools in hand, that the young people may actually change something for once.