I’ve long believed that Second Run is one of the best home video companies distributing to the English-speaking market. In part it's because their catalog never seeks to just scratch the surface of its more niche interests, but genuinely highlight films, primarily from undervalued Eastern Bloc countries (they have a great selection of Czech, Yugoslav, Polish, and Hungarian films), not well-known to Western audiences. When I was young I used to browse their site to find new filmmakers I’d never heard of elsewhere, it led to my love of the likes of Miklós Jancsó and František Vláčil. Another part is their largely no-frills approach, from their website straight out of 2005 to their design work that feels more economic than eye-popping. However a more personal association I have with them is one not as representative with the modern label, or any other disc distributors anymore: cruddy picture quality.

The first Criterion disc I bought was their re-release of Solaris. I was 17 or 18 and first getting into film in general, and starting what I imagine will be a lifelong obsession with Eastern European cinema. Not knowing that Criterion had made two different DVD editions, I realized the one I’d bought was a remarkable improvement over the disc I rented from Netflix (whose DVDs in the mail were probably more essential than anything else in my teenage years for allowing me the opportunity to expand my filmic horizons). The picture quality was crisp, the sound cleaned up, saturation more “natural,” and any trace damage on the original film scan was gone. It was like I was seeing something new, not an artifact from a country that had since dissolved. My Kino Lorber DVD of Stalker was a different matter altogether.

Andrei Tarkovsky’s cinema is largely remembered for his poetics, where the camera heightens light and time to something transcending the possible. It's a near-religious craft. However one thing that often seems missed by his imitators (Paul Schrader the most sterile of them) is his visceral sense of texture—the dust hanging in the morning light, the weaves of linen hanging off a mother’s shoulders, the water streaming over a rock, the grass enveloping a body. Tarkovsky’s cinema is a tactile one. And for the longest time, outside of repertory screenings, the way that most people would experience this is through really egregious scans, with muddy pictures and worthless subtitles. The incredible part is the beauty still crept through.

Tarkovsky, the most famous and internationally renowned filmmaker to come out of the Soviet Union is one thing, the rest of the Eastern Bloc is another. The West’s interaction with the film industries from the other side of the Curtain was largely made up of massive national blockbusters (Bondarchuk’s War and Peace, Konchalovsky’s Siberiade) or the more daring, avant-garde films that would make rounds at international film festivals, both of which were sent out with the intent of bringing prestige to the communist countries, even if some were lightly countercultural. The nature of having two massive powers carving the world into their respective monocultures for almost 50 years is going to lead to both developing parallel conversations about film aesthetics and, with the collapse of a unified political bloc after the Sino-Soviet split, made it so the Eastern Europeans had a much smaller and less broad reach than their western counterparts.

And while evolutions in film criticism have always accompanied movements within the western canon, even to this day little is discussed about Eastern Bloc criticism beyond the Montage theorists of the early silent days. The understanding of Eastern and Central European film in the United States and beyond is behind, and the home video market reflects that compared to other national industries.

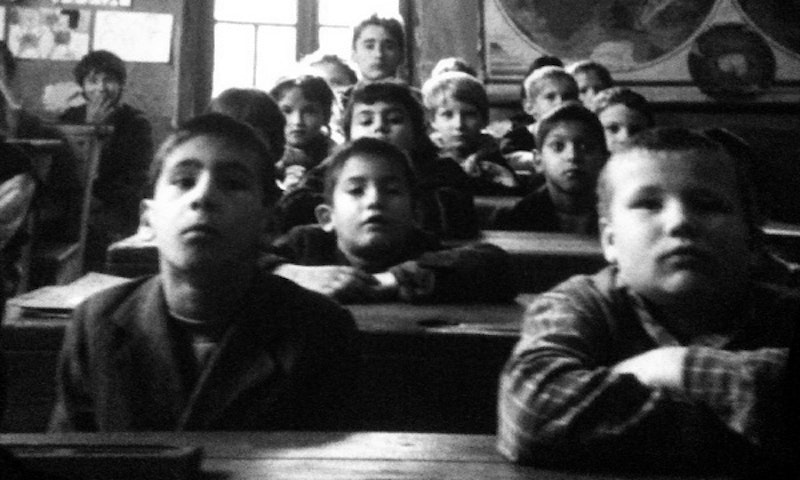

There was always a sense of discovery to seeing a 50-year-old, magnificently rendered image as if it was filtered through a mini-DV camera. It separated the object from the alien world it was created in, it offered a glimpse into something long-since gone—it was an artifact. It’s altogether different now. The USSR’s biggest film studio releases a lot of their archives for free on YouTube, and the way for a young film fan to see Béla Tarr’s films aren’t through dicey PAL scans, but meticulous 4K restorations that get sent on cross-country tours to accompany Blu-ray releases. Just this last weekend I watched Arbelos’ new restoration of (Tarr associate) György Fehér’s film Twilight, put out on home video by our old friend Second Run. The previously impossible-to-see movie can now be ordered on Amazon with impeccable image quality. It’s hard not to see it as an overall step forward (and I hope this happens with Fehér’s other films, I desperately want to see his adaptation of The Postman Always Rings Twice), but I wonder if this will also lead to an expectation of quality as being necessary to garner interest.

Many cult films have newfound followings by way of restorations. Possession, a film that was notoriously hard to get a proper cut of, is perhaps the biggest example, with its 2014 Mondo restoration gradually expanding the film’s base and turning it into a meme as a shock-movie. The same happened more recently with the Soviet war epic Come and See, another which I have some godawful Kino DVD of lying around somewhere. Criterion was passing around a new restoration just before the pandemic took hold in the US, and the film which went from having a specific niche interest became fodder for reaction videos. Both of these restorations are beautiful and have brought innumerable eyes to otherwise unseen films, but I wonder if it weren’t for such high quality of the releases these movies could’ve had the same kind of attention. At a point in time where even no-budget independent films are expected to have a kind of visual parity with multi-million dollar movies, I’m worried that the same entitlement to quality might limit people’s curiosity as much as it’s sparked by these handful of restorations.