The tide of j-horror seems to be receding. A few years ago you couldn't visit a cinema without being offered at least one Japanese or Japanese-derived horror movie. The Ring, The Grudge, and their sequels were at least frightening; the genre reached its nadir in Pulse, a boring movie that wasted Kristen Bell and featured naked, pasty ghosts that resembled Ben Kingsley. By now a ghoul staring out of a television or crawling awkwardly along the ceiling seems more a parody than terrifying. America has used up the stylistic elaborations of Japanese horror and worn them thin. If Pulse isn't enough to convince you, check out Dark Water, a film that I saw in theaters but had forgotten about until recently.

I recently re-watched The Maltese Falcon and enjoyed it; this sent me on a Criterion Collection DVD buying spree (a very short one, since the Criterion collection has no qualms about price). My order included the 1964 Japanese film Kwaidan. This film, directed by the legendary Masaki Kobayashi, includes all of the Japanese horror clichés that felt fresh and terrifying only four or five years ago: the hair, the groaning houses, the pallid faces peering out of inanimate objects. Of course these ideas existed in Japanese ghost stories before the dawn of cinema; but Kwaidan clearly helped cement a certain style of filming them. That said, Kwaidan is not scary—it exudes the stately dread of Edgar Allen Poe rather that the sharp, startling menace of The Ring.

A man with the unlikely and extremely ugly name Lafcadio Hearn wrote Kwaidan (the book on which the movie was based) in 1904. Hearn was not Japanese, although he became a naturalized Japanese citizen (taking the more musical name Koizumi Yakumo); he lived in Japan from 1890 to 1904, the year of Kwaidan's publication and his death. Kwaidan, or Kaidan in a more modern transliteration, is the Japanese word for ghost story, and the book collects a great number of them. The movie selects only four. The stories, which I read a few years ago, feel thoroughly Japanese, yet a foreign barbarian wrote them. This reveals quite an amusing pedigree for the American version of The Grudge: it's an American remake of a Japanese horror film that referenced an earlier Japanese horror film that adapted a self-consciously Japanese book of ghost stories written by a Greek-Irish Japanophile.

Trivia aside, the movie merits watching—it may not frighten the viewer, but Kobayashi builds an atmosphere of intense weirdness and dread, and the lavishly artificial sets provide some stunning images. Kobayashi enjoys lingering in his scenes. He takes his time with shots of his characters' faces, which range from chilling blankness to carnivalesque contortion. He keeps dialog minimal and often mutes environmental sounds in favor of discordant music or non-specific, suggestive noise.

The film is broken into four segments. The first and second, "The Black Hair" and "The Woman of the Snow" are the most complex and affecting. "The Black Hair" recounts the story of a samurai who leaves his devoted wife to marry a rich merchant's daughter. He and the rich girl don't get along, and he wishes he could return to his sweet former wife; after a fashion, he does. Things don't end well, and yes, we do get a low-tech ancestor of the hair monster from The Grudge. The supernatural touch remains light and Rentaro Mikuni gives a surprisingly tender performance as the samurai. He begins the segment in the grim, barking mode of so many movie samurai, but by the end he has revealed some depth.

"The Woman of the Snow" most resembles a fairytale and showcases a stunning, genuinely unsettling performance by Keiko Kishi, who plays the eponymous Woman of the Snow with a magnetic, blank evil. The segment tells the story of a woodcutter who witnesses a horrific supernatural murder during a snowstorm; after he recovers he marries a lovely young woman who, in a certain light, resembles the killer of that cold evening. The final, hyper-stylized scene of this segment is worth the price of the whole movie.

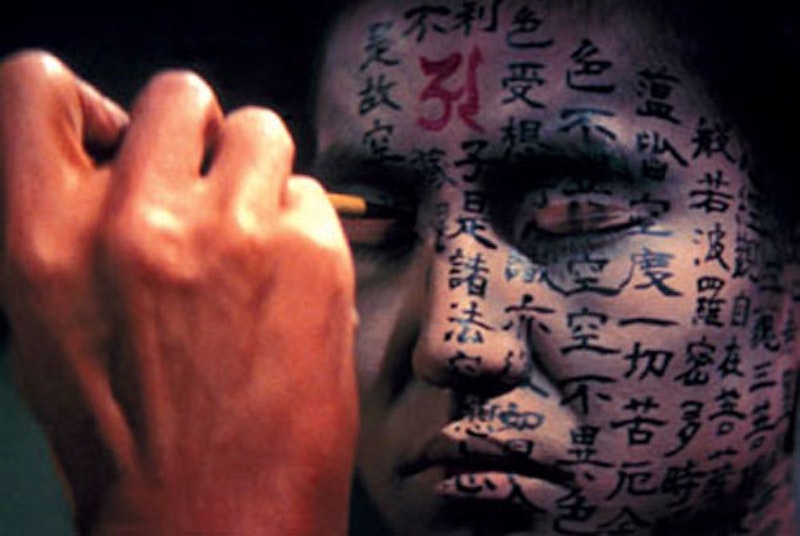

The second half abandons the sensitive family psychology of the first part and is ultimately much weaker. "Hoichi the Earless" is a visually magnificent but ultimately kind of silly Buddhist parable. It features some amusingly dramaturgical stagings of a sea battle between the legendary Heike and Genji clans, and some blistering biwa solos. Its message about the human condition boils down to "don't mess with ghosts."

"In a Cup of Tea" starts out with the eerie scene of Noboru Nakaya leering at Kanemon Nakamura from a bowl of water and winds down well before it ends with more leering and some shrieking. It's nightmarish in a way that recalls Kafka, but ultimately the supernatural fooling around and slight framing story don't give its characters too much room to do anything other than mince around and scream.

Far be it from me to suggest that the j-horror genre deserves rigorous study-if you've seen The Grudge and The Ring you can pretty much understand everything there is to know about it. But it is nonetheless interesting to watch this more thoughtful, more complex, and vastly less frightening forbearer of the blue-tinted horror movies of the past few years. Kwaidan offers the viewer much more than the lingering violence of The Grudge and The Ring. Its superlative visual presence and unexpected, intimate sensitivity are much more memorable than its introduction of scary floating hair to the visual vocabulary of cinema.