The title is a reference to the protagonist’s supposedly encompassing worldview, but the newest Woody Allen inanity, Whatever Works, suffers from the same terminal navel-gazing contempt for others that define his worst films. The problem with Allen isn’t only that he’s made a lot of bad movies. The bigger issue is that even his good ones feel hermetically sealed, redeemed either by unpretentiousness (let us praise Bananas and Sleeper), first-rate actors (Crimes and Misdemeanors, the Gene Wilder sequence of Everything You Always Wanted To Know About Sex), or, most likely, great cinematographers, particularly the Gordon Willis era of Annie Hall through The Purple Rose of Cairo. It takes talented collaborators, in other words, to breathe some life into Allen’s stale batch of preoccupations and shameless literary/cinematic pilfering, and even when they manage the task, they still have to compete with his tiresome non-inclusive ideology and bland aesthetic sense.

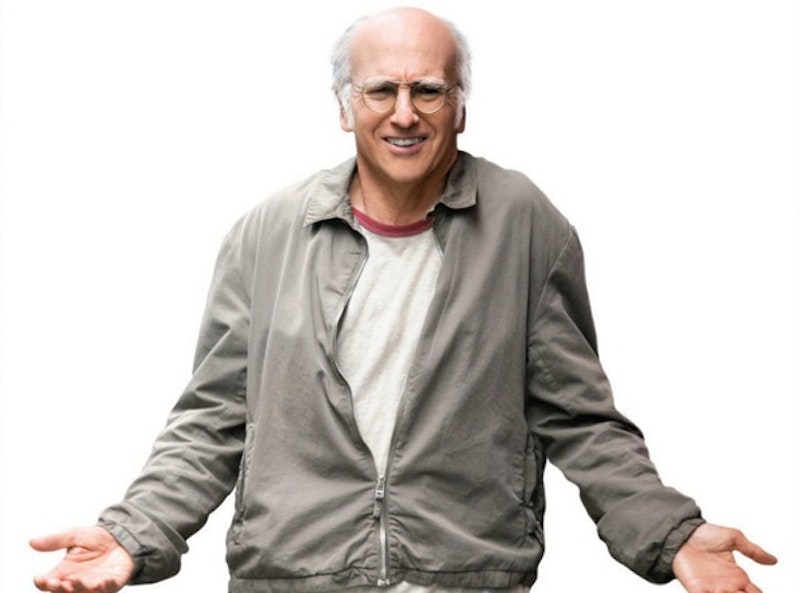

The stock Allen character, whether played by the director or a doppelganger like Larry David in Whatever Works, is always the same burbling brook of Borscht Belt one-liners, tellingly laughed at by no one around him. No surprise that his best movies, Annie Hall and Manhattan, are the ones where intelligent women and friends become frequently tired of his act, or that his worst, like Stardust Memories and this new one, posit this conversation-by-rimshot as the voice of reason amid chaos. The main source of humor in every Woody Allen movie is the nebbish character’s logorrheic disappointment, mistrust, or disapproval of the dumber (usually goyim) people’s ideas and actions. When the writing’s funny and the dumber characters have some backbone and complexity, this can be tolerable, even lovely. When the writing’s bad, the supposedly smart character is hateful, and the dumber ones are offensive clichés, this is disgusting. Enter Larry David.

Having apparently filched all he could from Bergman, Fellini, and 19th-century Russian novels, Allen’s now just recycling his own movies for material. So we get the same old morbid-Jewish-asshole character, Boris Yelnikoff (did you know that Woody’s read some Russian literature?), who addresses the camera Annie Hall-style, has a couple of buddies who yammer around a restaurant table like the showbiz vets that open Broadway Danny Rose, and who gets to play Pygmalion with an uneducated, sexually liberated shiksa (Evan Rachel Wood) like in Mighty Aphrodite. We’re told many times, usually by Yelknikoff himself, that the man’s a “genius” physicist who was once shortlisted for a Nobel prize for “string theory,” though Allen doesn’t even bother to do anything with this morsel of characterization, much less discuss physics in the script. For Allen, it’s enough to pile on unspecified interests and neuroses and claim he’s created a character. So even a “genius” like Yelnikoff still talks in bargain-bin Woodyisms: “Our marriage hasn’t exactly been a bed of roses; botanically speaking, you’re more of a Venus flytrap.” Cue foghorn.

The script’s non-comedic moments are just as clunky, like always. Allen’s cinematic world is one where people say of themselves, “I’m very romantic by nature” just so he can avoid actually showing them acting romantically. Or where a photographer tells another artist, “This is amazing; you’ve managed to make an existential statement about the nature of eroticism” without specifying what that statement may be or, more to the point, why we should give a damn. Allen doesn’t even show us the pictures in question, since his whole game is about intellectual signifiers, not actual intellect.

Allen’s never been kind to non-New Yorkers in his movies, but Whatever Works is particularly loathsome in its treatment of Southerners, all of whom—like in real life!—are sexually repressed, uneducated Jesus freaks. I’m not averse to caricature in art, but I am averse to laziness, which is all Allen’s grotesques amount to. Wood’s character literally emerges out of the garbage and inserts herself into Yelnikoff’s life, spouting yokel hokum like a story about the time she lost her virginity “behind the tent at the fish fry.” His unending verbal abuse of this girl just rolls right off her because she’s so enraptured by his intellect, which, like Allen’s, is little more than passing familiarity with Existentialism 101 and an above-average vocabulary. He clearly despises her, yet she develops a crush on him anyway and he goes along with it, mainly because he’s able to shape her into some ersatz (yet still non-threatening) version of himself; she’s a blank slate, and a nubile, frequently tank-topped one at that. In case you held out hope that this scenario would develop into anything other than a lecherous sexual fantasy, Wood is given the cruel task of enunciating one of the most transparently self-pitying lines in Woody Allen history: “I don’t like normal, healthy men; I like you.”

By the time the girl’s parents (Patricia Clarkson and Ed Begley, Jr., who, along with co-star Michael McKean, should know better than to stoop to this) show up and are duly liberated by Manhattan’s joie de vivre (or se we assume; New York looks like a sitcom set in Whatever Works), this hot mess is already so cinematically empty that even they can’t save it.

Any conversation about Allen’s talent and career eventually comes down to whether his extraordinary prolificacy works for or against him. “But he made Manhattan!” defenders cry, “So what about the hours of pretentious, unfunny garbage he’s cranked out over the last 40 years?” Normally I’ll grant an artist endless leeway when one great work appears amid a flow of bad ones. But, by his own design, Allen’s career refutes this generosity. As his resolutely unchanging aesthetics—the twinkly jazz, the stirring classical music, the silent-era credits—exhibit, Allen’s movies all come from the same place. They’re all about the same kind of people, with the same kind of mundane drama dressed up in high-cultural clothes. Occasionally they’re funny, less occasionally they’re poignant, but all these films move inward, away from the world, and this self-absorption comes to the fore in his worst ones. Shorn of a few inspired chuckles or beautiful photography, we see the disregard that Allen has for the world outside his own head and experience—and sadly, it doesn’t look all that different from Annie Hall. It’s not as pretty, or well performed, or as full of recognizable life, but it points to the same conclusion: Isn’t this self-absorbed, obnoxious Jewish guy adorable? Doesn’t he deserve to fuck a beautiful shiksa like Diane Keaton, Mia Farrow, Mira Sorvino, or Evan Rachel Wood? And isn’t he smarter than all of them?

No one’s required to see every lazy minor effort like Whatever Works that the director churns out so proficiently, but anyone who does will walk away with that familiar Woody Allen taste in their mouth, the one that makes you feel used and a little taken for granted. And then someone will tell you later that an older Allen movie—Hannah and Her Sisters, or Deconstructing Harry, or Love & Death—is different, that it’s not as groan-inducing as his typical crap. And maybe it is, but you’ll know in your heart that it won’t really be that different from Whatever Works, and who’s got the time? Life’s too short to go rooting around in the scrap heap of an artist whose entire career has been built on indifference to people unlike himself.

Whatever Works, directed by Woody Allen. Sony Pictures Classics, 92 min., rated PG-13. Now kvetching in New York and L.A.