Every now and again you see a film that is so unique and visually arresting that, by the time the lights go up and the credits roll, you are paralyzed in your seat. Words are pointless as you leave the theater. You’re drunk. You’re in love. “Holy crap,” is about all that works.

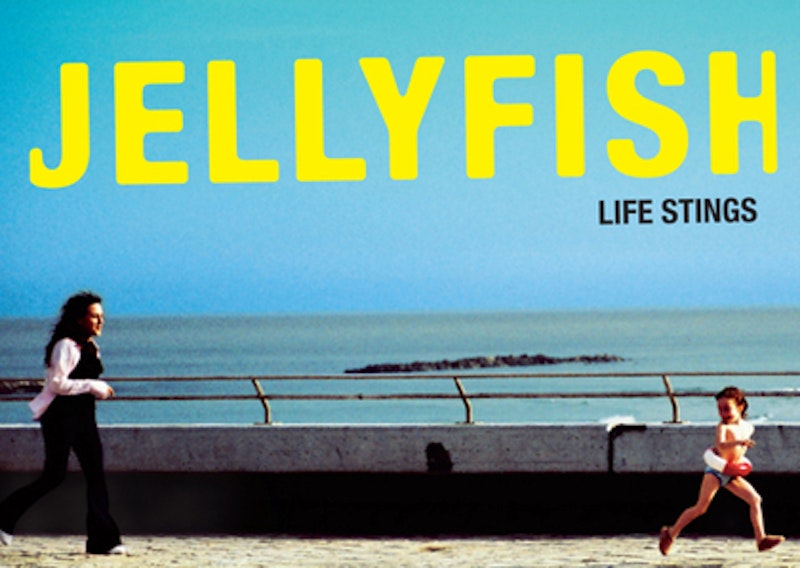

Last year’s one-eyed sensation Diving Bell and The Butterfly made me feel that way; the equally grisly and tender Pan’s Labyrinth did as well. Though much less widely seen, Jellyfish (or “Meduzot” in Hebrew) had the same full-body-hit effect. Written and directed by Israeli husband-wife team Etgar Keret and Shira Geffen, the film tells the stories of three women whose lives intermingle loosely to paint an achingly sad but often whimsical picture of modern Tel Aviv.

Is there a main story here? Not exactly. One woman finds a lost, mute child on the beach who was seemingly birthed by the sea itself. One woman finds herself locked in a bathroom stall at her own wedding reception. Another woman who can’t speak Hebrew, finds herself taking care of a lonely old Israeli lady who learns to communicate with her nursemaid with the only language that really works everywhere—empathy.

The real star of the film is Batia, (played with a sallow grace by Sarah Adler), who is a struggling twentysomething party caterer with dreams of being a photographer. The daughter of a prominent Israeli activist whose shining face is all over the city in billboards, (her mother promises housing for every Israeli), Batia is embarrassed to find that she can’t seem to make it on her own, and she lives in a moldy, electricity-free apartment that seems each day to be both haunted with ghosts and flooded with more water. Escaping her drab existence, she goes on walks by the beach, where she drifts in and out of an existential dream-state. One day on the beach, she finds a little girl wandering alone, naked, save for an old-fashioned inflatable lifesaver tube. The girl, though apparently separated from her parents, is incredibly cheerful, wearing a perpetual cherubic smile, and she takes instantly to the thorny Batia. Touched, Batia tries to help the lost girl, first going to the police who have no idea where the girl came from. With nowhere to go, Batia takes her along to her catering jobs, where the little girl disappears and reappears like an apparition, hiding under the party tables, wandering the bustling kitchens, and taking to the empty night streets.

Serving yet another cheapo wedding reception with blasting music and flashing lights, the harried, hollow-eyed Batia (she’s always about to be fired) comes in brief contact with the next heroine of the film, the put-upon bride, Keren. Stuck in said bathroom stall, the bride, dress and all, ends up fracturing her leg trying to climb out, forcing her and her young husband to stay in a grimy Tel Aviv hotel for their honeymoon. Her restless husband, while escaping his angry young wife’s laments for a smoke on the hotel balcony, meets a curvaceous, mysterious fellow hotel guest to whom he finds he is instantly attracted. It’s a dangerous situation and he knows it: while his bride waits anxiously for him in the hotel room, hubbie keeps sneaking out to talk with the mystery lady. The more he talks to her, the more he finds that he knows and likes this woman, a complete stranger, better than he even knows and likes his wife.

At the reception party we also meet Joy, a middle-aged Filipino nurse who makes ends meet by caring for the aforementioned cranky old Israeli lady, Malka (played with devilish zest by Zaharira Harifai) who has grown too difficult for her busy intellectual daughter to handle. The daughter hires Joy to make sure Malka doesn’t hurt herself or forget where she is when she runs her daily errands. We find that, despite their different backgrounds, both Joy and Malka are incredibly lonely, as they have, for very different reasons, been isolated and separated from their families. While Joy is at first violently resisted by the fractious old lady, as they spend more and more time together, Malka realizes that without her estranged daughter to keep her company, Joy is the only person she has, the only person left on earth who cares about her even a little. With no language to bind them, it is something to see the two women quietly find solace in each other’s surprising similarities. Though Malka is clearly above Joy in Israel’s caste system (Filipino immigrants flock here to find jobs in the service industry) and never attempts to break that tradition, the two women learn to understand each other as two broken mothers who, without the presence of their children’s love, are lost at sea and sinking fast.

As the title would suggest, sea themes connect the three women—like the amorphous creature of the film’s title, they all seem to be adrift. Batia’s only home is a flooded cesspool. Keren laments that she was supposed to be on a cruise for her honeymoon and now, she can feel her husband slipping away to someone else. Joy’s family, surviving on her foreign wages, calls out to her in vain across the ocean. Making her film debut, the amazingly subtle Ma-nenita De Latorre (Joy) often stands in a dirty phone booth and promises her son, with tears in her eyes, that instead of coming home to see him, she will try and send him the best birthday presents he can imagine. That perfect birthday present happens to be a big wooden toy ship that Joy cannot afford.

Keret, a rising international star whose collections of smart-alecky short short fiction have been best-sellers in the Mideast for years, (check out his dark The Girl On The Fridge) was also the morbid mind behind last-year’s critical darling Wristcutters: A Love Story; another gem. Like in Wristcutters, which describes a post-apocalyptic landscape made only for suicide victims, Keret and Geffen’s Tel Aviv seems to be remarkably familiar and fantastical at the same time.

Thankfully, Keret has a wonderful ability to write stories that slip organically in and out of fixed narrative structure. Batia is the catalyst of Jellyfish’s surrealist streak and the dream-like underwater scenes between Batia and the maybe-real, maybe imagined little lost girl, are visual wonders. In the film’s most gorgeous shot, the two lost souls simply look at each other, nose to nose, while floating in the azure water. It is one of those moments that raise the hair on the back of your neck, when you look over at the person sitting next to you in the theater and whisper, are you seeing this?

Keret’s greatest gift is to use biting realism and a painterly surrealism in his works to create a living, breathing world that is both ugly and magical at once, desolately lonely and full of friends we haven’t met, cruel and kind, empty and full—real and of our own twisted imaginations. Perhaps the success of Diving Bell and Pan’s Labyrinth lay in the visceral way were thrust into the circuitous corridors of the subconscious—while a real, violent war raged in Franco’s Spain (and inside the brain tissue of Jean-Dominique Bauby) we were also given a tour of the still-beautiful side of life—the peacefulness of a drive in a convertible on a summer’s afternoon, the breathtaking remains of an ancient underground kingdom.

In Jellyfish, Keret and Geffen have crafted a duality that is something equally special—they bring us under the surface of these three rather taciturn ladies to show how magical life can be within the dull reality of modern urban life.

Like at most low-budget foreign films that elbow their way into the smaller screens at the Landmark or Lamelle theaters here in Los Angeles, I was saddened but not surprised to see the Jellyfish’s theater was almost completely empty as the film started. And it was Friday. As I quietly shared my popcorn with a friend, I asked a question I often ask when seeing little movies like this. How do these theaters stay in business? And then, feeling sub-conscious: How come nobody wanted to see this but us?

A week later, after screaming my head off about Jellyfish to anyone who would listen, I wondered: why do I bother? Nobody has heard of Keret or the movie. I looked to see where else the film was playing and saw that, after a week at two theaters in Los Angeles it was gone. I told my folks to see it in Chicago and they found that they couldn’t. Never came there. But Batman was still playing in 20 theaters, Mom said sarcastically—two months after it was released.

What would happen if a diamond in the rough like this were given a better chance to succeed? What if, for one week, The Dark Knight (which was pretty darn good too, what can I say) and its gargantuan ad machine was swapped with Jellyfish? Shouldn’t a generation’s art be available for all to witness? Should Kansas and Idaho and Chicago’s suburbs be deprived of Jellyfish?

Maybe it’s a lost cause. But this is why I see movies. To see movies like Jellyfish. To feel the hair on the back of my neck stand up. To teeter out of the darkness gasping for air, like after a first kiss that’s not really the first.