Paul Thomas Anderson’s seventh film, an adaptation of Thomas Pynchon’s novel Inherent Vice, is not an incoherent mess and it’s not a slapstick comedy like 22 Jump Street. When Anderson said the cartoon Tom & Jerry had a major influence on production, some assumed the movie would be broad, silly, and accessible, full of “the best fart jokes and poop jokes” like the director promised. I’d love to see PTA do a straight comedy, but this ain’t it. Inherent Vice is a movie you’ll have to watch multiple times to even get your head straight on about what happens. Makes total sense why it was saved for after Christmas—this is a crowd teaser, not pleaser. The Sunday matinee audience I saw it with let out a collective groan of confusion and “That’s it?” as the titles began to roll, and I started to think about other directors of Anderson’s generation and what they’re making now. Anderson established himself in the late 90s, breaking through with his second film Boogie Nights and getting lumped in with other cinephile college drop-outs in their 20s who were making the word “auteur” more palatable to investors. Wes Anderson, Steven Soderbergh, Darren Aronofsky, Spike Jonze, and David O. Russell have all survived, but none have kept their body of work as pure and vibrant as PTA, with the exception of Anderson, who has stuck with and developed his vision, but he’s gotten less interesting, exciting and mysterious.

Making a movie knowing that it has to be seen two, three, four times at least to get the gist of it is pretty much impossible for anyone else in Hollywood. Frequently cited as the most critically acclaimed writer/director of his generation, PTA has free reign, but he’s a token auteur, one pure voice in a sea of polluted product, borne out of compromise, committee, money problems, or pure obligation. He referred to great films as “moveable feasts” in a recent interview with Marc Maron: they’re supposed to come with you through life, offering new perspective and insight as you get older. On that same podcast, Anderson talked about his favorite film, The Treasure of Sierra Madre, and how he’d seen it seven or eight times before it hit him right in the gut. This is characteristic of great art: books, albums, they move with you, fading or strengthening or moving sideways as time marches forward. You see different things in them. Anderson’s last film The Master is a great example: at the time, in 2012, I was nonplussed by how abstract the second half of the movie was compared to the first, and feeling confused, like I had missed something, when the credits rolled after Philip Seymour Hoffman sang about taking Joaquin Phoenix on a slow boat to China. The crowd that evening let out the same disgruntled sigh, tricked once again by an arty director with his head in the clouds. Re-watching it late last year, the first time since Hoffman’s death, I was floored by the film, and finally saw the obvious unrequited romance between Hoffman and Phoenix, the relationship that the movie rests on. Two years on, The Master continues to resonate and change.

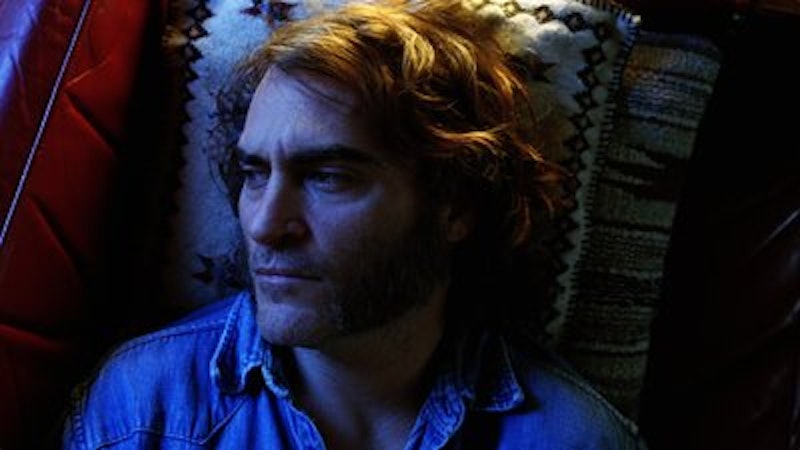

Inherent Vice is more of the same only insofar as it’s Anderson doing exactly what he wants, and getting permission and money from a lot of powerful people. I mean, Pynchon—he’s in the movie. Don’t know where, but man, dude got Thomas Pynchon to not only sign off on an adaptation of his work, but he got the guy to be in the movie, albeit secretly. Joaquin Phoenix’s character Doc is a jolly and endearingly confused hippie, perma-stoned and lost after his girlfriend leaves him. Doc, a private investigator as well as a certified doctor, runs into dozens of people that all drop clues about a mysterious organization called the Golden Fang, a dentist’s union and a front.

Inherent Vice is a shaggy dog story, and the particulars of “the case” mean absolutely nothing. This is a movie about being lost and lonely, missing love you’re starting to think may never be near again. All the gumshoe deal-making and plans are the slapstick he was talking about—at its center, Inherent Vice is about paranoia and loss. Beautifully shot as always, Anderson is able to explore color again after the drab settings of The Master and There Will Be Blood. Zebra print couches, neon orange chaise lounges, bungalows, costumes, furniture, and a lot of garbage from the late 1960s/early 70s makes for more interesting viewing than sand or water. Every shot, angle and cut is as deliberate and single-minded as possible. I even get the distinct impression, as with The Master, that PTA went into this without a fully formed script or vision of what the movie vs. the book would end up being. The editing and weirdness of the second half of The Master is less apparent here, but from the way he talked about it on Marc Maron’s show, re-writes, re-shoots, and improvisation are all over this movie.

I won’t pretend to understand anything about the movie’s circuitry or insanely complex story, but I did feel that Inherent Vice nailed its mood and is what it intended to be: a beguiling B-movie that would’ve been playing all day at whatever video store Anderson worked at. It portrays the feeling of being stoned in a masterful and nuanced way: all the paranoia ultimately leading to nothing, the bright colors, the slowed reaction time, impaired memory, the hazy wash of the mind and memories as we try to hold on to what we once had. Inherent Vice might be a minor work, but let’s recognize how lucky we are to have Anderson working and properly funded, because he has no peer in American cinema: no one makes movies to last like PTA these days.

—Follow Nicky Smith on Twitter: @MUGGER1992