Nineteen-Eighty-Seven saw James Bond return to form. Roger Moore was out, Timothy Dalton was in, and The Living Daylights is a significant step up for the franchise from that fact alone. Unfortunately, not much else has changed. But the difference in quality is still huge.

Dalton wanted to be more faithful to Ian Fleming’s original writings, and the first act of his first movie is adaptation of the 1962 short story “The Living Daylights.” It doesn’t have the world-weariness of the prose tale, but the plot’s the same: Bond’s sent to Bratislava (Berlin in the story) to get a Soviet defector across to the West safely, and duels with a Russian sniper. The film goes on from there, and if it goes in directions Fleming never intended, it still works for longer than you’d think.

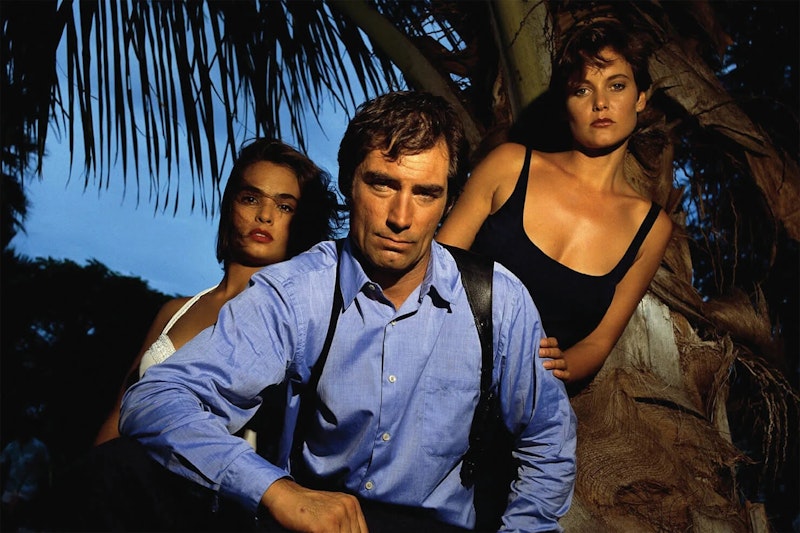

The defector, General Koskov of the KGB (Jeroen Krabbé), is taken to the home of M (Robert Brown), the head of MI6. There, Koskov says that the new head of the KGB, General Pushkin (John Rhys-Davies), intends draconian action against Western spies. Koskov’s abducted, and Bond’s assigned to kill Pushkin, who he respects. He takes the assignment, believing Pushkin’s responsible for the death of his colleague, agent 004. But then, returning to Bratislava, Bond encounters the sniper from his earlier mission, Kara Milovy (Maryam d’Abo) and learns that Koskov’s whole story’s a ruse. Bond and Milovy follow a trail through Vienna, to Tangiers, then on to Afghanistan where they work with the Mujahideen, thwart a major drug shipment, and find that the real villain is an American arms dealer (Joe Don Baker).

That’s a lot of plot, but a couple of things stand out. We see Bond’s boss at home; the world of 007 expands a little with this sense of his MI6 overlords as actual people. Bond has motivations for this mission. His choices in the first act (taken from the short story) define what happens after. His past history with General Pushkin shapes the choices he makes on his mission. And Dalton, to this day perhaps the most skilled actor to play Bond, brings that out. This isn’t the unflappable Bond of Moore or even Connery, undertaking missions out of duty. For this Bond, it’s personal.

Almost on his own Dalton carries the film, conjuring up a grim world of spies and assassins, selling the tension of a man on deadly business. But beyond the professional government killer, he also lets you believe in Bond as a real human (or as close as you want to get). There’s a bit where Kara Milovy goes to get him a drink, which she names as a martini, shaken and not stirred. Dalton smiles and says with surprise and warmth “You remembered!”—and what surely would’ve been a punchline under Moore and probably Connery is touching, humanizing the character and his relationship with his leading lady.

That’s good, but the problem is that Dalton’s too often a man on an island. D’Abo is fine in a role that doesn’t make a lot of sense, but Rhys-Davies is underused and Krabbé’s not memorable. Baker gives a workmanlike performance, but his character doesn’t receive the build-up necessary to establish him as a force capable of being the mover and shaker behind events. There isn’t the gravitas or depth to him that a major villain needs, and the action of the climax can’t match a major set-piece at the end of the second act.

The film’s directed by John Glen, his fourth consecutive Bond film, and the script’s by Richard Maibaum and Michael G. Wilson, also for the fourth consecutive time. They do elevate their respective games. The plot’s tighter, Dalton gets more interesting material to play with, and Glen handles the action scenes with skill. But the weaknesses are still apparent—unlikely plot points (Bond taken to Afghanistan is improbable), a dubious grasp of current affairs (the use of the Mujahideen is bizarre), and an inability to distinguish between good gags and bad (a chase ending with a toboggan ride in a cello case is easily the worst part of the film).

Still, the conscious attempt to present a more grounded Bond succeeds. There are no alphabet-soup spy agencies, few gadgets, and the villain’s lair is just a largish house crammed with military memorabilia and a few low-tech traps. It’s grimmer and grittier, and it succeeds, even if it doesn’t much feel like the high adventure of earlier Bonds. There’s a convincing note of paranoia that feels right for the 1980s, as does an assassination attempt involving a souped-up Sony Walkman. (That takes place, incidentally, at the Viennese amusement park where the Ferris wheel Joseph Cotton and Orson Welles rode in The Third Man is visible in the background. Whether it’s a deliberate reference or not, it works to heighten the sense of a gray, dangerous world.)

The final result is flawed but intensely watchable in a way that Bond movies hadn’t been in some time—at least the best in 10 years, and perhaps well before that. The previous Bond films of the 1980s were bad action movies, while this is a good action movie. And yet it lacks the weird pulpy edge the best Bond films bring. There’s no super-scientific gizmo or super-gifted antagonist to grip the imagination. It’s unusual for a Bond movie in that Bond is interesting, as a character as well as a presence on screen, but not much else is. Maybe in 1987 that’s just what the series needed.