Cinema of the Weimar era ushered in a new way of looking into the human mind. Man has always been a reflective but something changed once Sigmund Freud opened up the door to his psychoanalytic study. People begin to think about thinking. The very idea of consciousness began to take precedence in trying to understand the meaning of life and man.

In addition, Freud introduced the notion of the “unconscious,” which was the key to the mind. Patients only needed to probe the depths of the unconscious desires, weaknesses, and fears and they’d be cured of their psychological conditions. In many ways, Freud was the first to point to the mind-body connection in a psychological way. Freud’s contribution to the psychology of man is unmistakably significant and has given birth to many other psychoanalytic approaches, such as Jacques Lacan’s unique psychoanalysis. Over time it lost its healing power and entered the hallways of academia, where psychoanalytic theory was applied over and over again into literature, art, film, and even philosophy and theology.

At the time of its advent, people (especially upper classes) were taken by this new approach in solving their problems. Man turned inward. Society and community as a whole began to lose its power as the primary mover, and humans became concerned with themselves.

One of the hallmarks of Weimar cinema is precisely this focus on individual consciousness and subconscious desires that often turn deadly. Modernity brought on an existential malaise and boredom, and otherwise happy people retreated and hid behind their psychological conditions, which may have been created by the inward turn to begin with.

G. W. Pabst’s Secrets of a Soul (1926) is an explicitly psychoanalytic film that deals with one man’s obsession. Pabst made the film with help of Freud’s associates, Dr. Hanns Sachs and Dr. Karl Abraham. Werner Krauss plays a professor of chemistry, who becomes obsessed with the notion that his lovely wife doesn’t love him, and instead will choose her cousin. As it turns out, the cousin has lived in Sumatra (he is an explorer) and has announced that he’s coming back, and would love to see them.

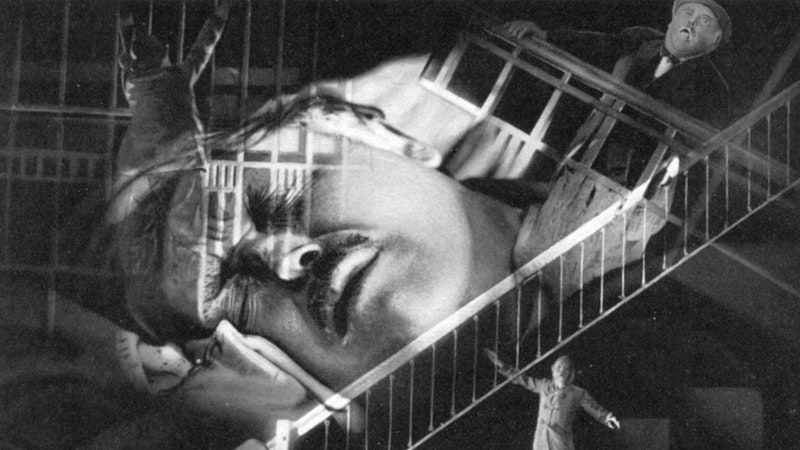

This, and a local murder by razor triggers something awful in the professor. He begins to see a fantasy of his wife’s affair. What’s worse, he becomes obsessed with taking a knife and killing his wife. As a result, he stops using knives altogether, which as one can imagine, makes eating difficult. He quickly descends into darkness, especially following a bizarre dream. There are fragmented images of the professor’s relationship with his wife and her cousin. Mocking faces, strange towers, Indian statues are all accompanied by one theme: his wife is rejecting him for who he is and choosing her cousin. In reality, the wife’s relationship with the cousin is innocent, and as one would expect, purely familial. It’s all in the professor’s mind.

In order to cure himself, he visits a psychiatrist who thinks it’s best that the professor lives somewhere else during his treatment. What follows is a journey into the professor’s mind. It’s a straightforward psychoanalytic trajectory: the professor tells the psychiatrist all of his desires and fear; dreams are portals into the subconscious and the unconscious that reveal another piece of the mind puzzle; he and his wife have been unable to have children; the professor is almost cured but he needs to reach farther into the memory bank; and finally, he isolates his obsession with one childhood event: when his future wife chose to play with her cousin and not him.

Despite the fact that the professor appeared to be on a regressive trajectory—he lives with his mother during the treatment and she cuts his food into small pieces, rendering him a helpless child—his openness to psychoanalysis proves to be successful because he returns a cured man and happy to be home with his wife. In a sentimental epilogue, the pair have left the bustle of the city, moved into a cabin in the woods, and they have a baby.

Secrets of a Soul is a very creative “advertisement” for psychoanalysis. Pabst is clearly a believer in the method. As Siegfried Kracauer writes, “In his zeal for documentary objectivity, Pabst adheres anxiously to matter-of-fact statements: no shot assumes a symbolic function, no passage implies that the professor’s frustration may well mirror that of a multitude of Germans.” This is correct: if this is a mirror into the German soul, then it’s a mirror into a very selective population, the upper class that rejects religion and accepts modernity.

Nowhere in the film do we see the characters’ interest in God or religion, except the exotic Indic god that ends up being one of signs that the professor is suffering from a case of obsession. Both he and his wife are living a life of metropolitan modernity, which is somewhat rejected with the melodramatic epilogue. But even so, the great return isn’t the one to a monotheistic God, but into Nature, into the Heideggerian hut.