Ari Aster's 2019 film Midsommar is basically a feminist remake of the 1975 paranoid pagan 1973 classic The Wicker Man. Like all the best remakes, though, Midsommar makes you reconsider its source material. Re-watching The Wicker Man after seeing Aster's film, I realized that the earlier film was trying to burn down the patriarchy too.

Midsommar is structured as an abstracted feminist rape/revenge narrative. Dani Ardor (Florence Pugh) is traumatized when her sister kills herself and her parents through carbon monoxide poisoning. Her boyfriend, anthropology grad student Christian Hughes (Jack Reynor) is only distantly supportive; he cares more about his bro friends and career success than about Dani or her sadness. Despite their strained relationship, the two travel to Sweden with friends to observe a pagan community's midsummer rites. Christian participates in a sex ritual, and then Dani condemns him to death for being an unfaithful jerk and a bad boyfriend. The film ends with her crowned as the May Queen, smiling maniacally, and exulting in the comfort and empathy offered by the pagan community, which encourages her to embrace and express her feelings of pain, grief, and anger.

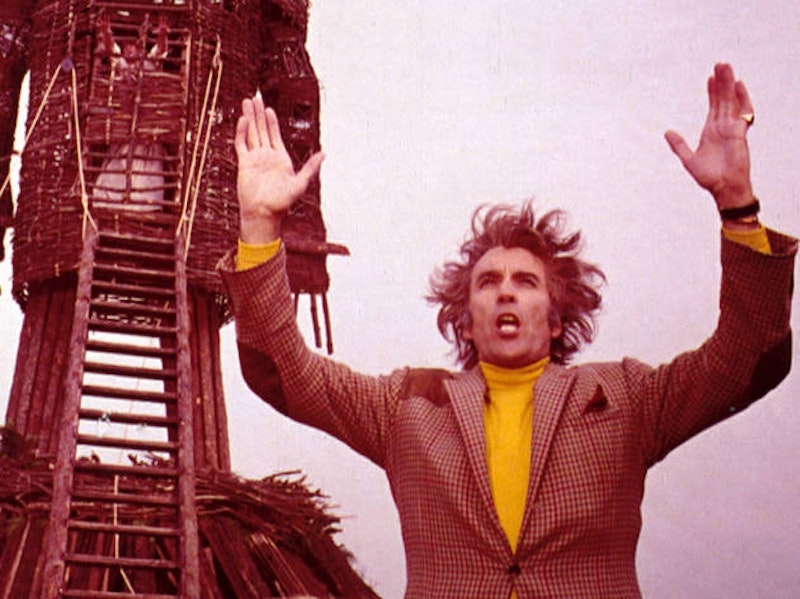

The Wicker Man is also about a bloodthirsty pagan community—this one on an island off the coast of Scotland. It doesn't have the same feminist themes though, not least because the protagonist is a guy—Sgt. Neil Howie (Edward Woodward.) Howie, a Christian, travels to Summerisle to investigate the disappearance of a young girl named Rowan. The islanders are unhelpful, and he suspects they’re planning to sacrifice the child to ensure a good harvest. Howie blunders about, increasingly horrified by the islanders’ casual attitude towards sex and nudity, until he discovers that it’s not Rowan, but himself who’s to be burned to death in the giant straw Wicker Man.

In Midsommar, the pagans are in closer touch with their emotion than the anthropologists who want to study rather than feel. Christian's male rigidity and stifled empathy is contrasted with the pagans, who (with some enhancement from psychedelics) communally moan and shriek and stagger about when someone is hurt, or gasp and thrash when someone nearby is having sex. The beautifully composed, long shots of communal ritual evokes a kind of maternal Triumph of the Will, in which the community becomes one with the trees in an orgy of blood and flowers.

The cinematography in The Wicker Man is less spectacular, but the gender dynamics are of a piece. "I represent the law!" Howie declares in outrage, as he glares disapprovingly at men in the tavern singing bawdy songs, or at naked girls jumping over a fire as a kind of prayer for fertility. In one of the film's infamous scenes, Howie—who’s a virgin—lies feverishly in bed while the innkeeper's daughter Willow (Britt Ekland) dances naked in the next room, banging on the wall in invitation. Midsommar is more focused on emotional intimacy and The Wicker Man is more blatantly sexual, but the contrast between male Christian rigidity and female openness is similar.

The Wicker Man also, in its own way, has Midsommar's rape/revenge dynamics. Through most of the film, the viewer’s led to believe that Rowan’s in danger of being violated and traumatized. Then, at the end, Howie is substituted for her as the victim. The movie's violence is first aimed at the girl and then it’s turned around and aimed at a man—as in Midsommar, Dani's trauma eventually incinerates Christian.

The movies warn of pagan horrors unleashed when you remove the patriarchal strictures on emotional and sexual expression, and let the women run willy-nilly in the pubs. But those warnings are really just an excuse to imagine the destructive, violent, sexy fun to be had when you let the women in the pubs and burn down the patriarchy. Howie’s an insufferable prig, bursting into classrooms to demand that girls stop talking about phallic symbols and nearly imploding with shame and rage when the innkeeper's daughter wants to sleep with him. You're rooting for him to get his, just as you root for the Swedes to take care of Christian's insufferable friend when he pees on their ancestral tree.

And yet, you also sympathize with Howie as he goes to his death. It's hard not to feel bad for the guy as you watch him pray to his God while being burned alive. The thing about revenge narratives is that, like The Wicker Man, they involve a doppelganger substitution. The hunted becomes the hunter, which means that, ultimately, the hunter wins. Howie’s the law at first, but he transgresses an older law—pissing on that ancestral tree—and it’s for that which he is killed.

Midsommar helps you see the way The Wicker Man sets patriarchy on fire. But watching The Wicker Man illuminates the way in which Midsommar isn't necessarily interested in incinerating the Christian law after all. Dani may be smiling because she's found an empathic community to hold her. But she's also smiling because she’s released from empathy, and can simply perform the bloody commands of ritual without guilt or even thought. The new queen looks a lot like the old king. Even when it's burning down, it's hard to escape the wicker man.