The James Bond film series has seen two huge upward leaps in quality over the course of its run. The first came when Timothy Dalton replaced Roger Moore, and brought a darker, grimmer tone to the films. The second when Dalton left the role. That had nothing to do with him. Everything else about the films changed between 1989, when Dalton’s second and final outing was released, and 1995, when GoldenEye finally reached theaters.

That six-year delay was caused due to legal and financial issues around the purchase of MGM. When the dust settled, Dalton’s contract had expired and producer Albert R. Broccoli’s health was deteriorating. Broccoli’s daughter Barbara and stepson Michael G. Wilson took over as producers. Wilson stepped aside from scripting, and with his collaborator Richard Maibaum now dead, a series of other writers worked on GoldenEye; the final script’s credited to Jeffrey Caine and Bruce Feirstein from a story by Michael France. A new director finally got to take a crack at Bond, New Zealander Martin Campbell. And there was a new lead actor.

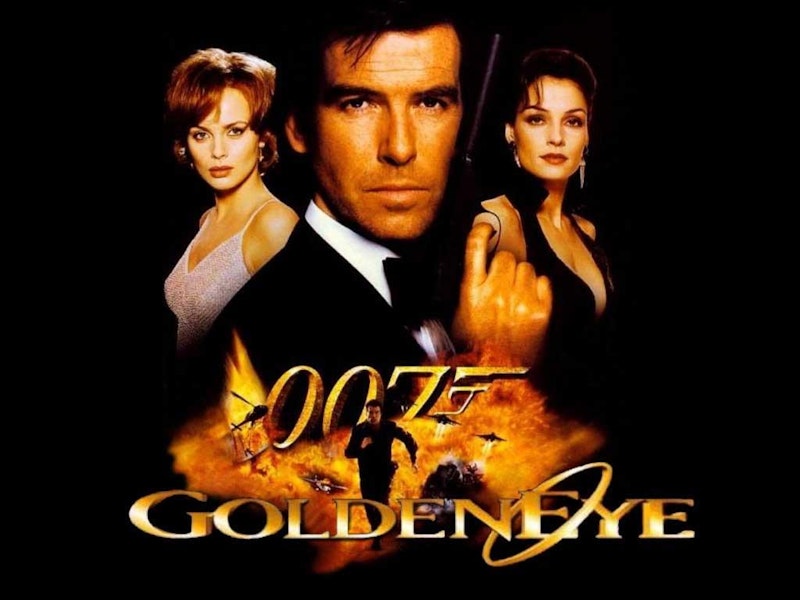

Pierce Brosnan could’ve been grown in a vat to play James Bond. Tall, dark, handsome, charismatic, capable of projecting threat and elegance at the same time, he embodied the archetypal 007. That’s a different kind of Bond than Dalton’s grittier take on the character, and it was what the series needed. The six years between 1989 and 1995 saw considerable change in the world, and the character of Bond needed to be re-established in a post-Soviet era. GoldenEye did that.

An opening sequence is set in Russia in 1986; MI6 agents 007 and 006 infiltrate a chemical weapons plant, things go awry, and Bond survives the explosion of the plant while 006, Alec Trevelyan (Sean Bean), is left for dead. In the present, Bond passes a psychological assessment by seducing the examiner, then fails to stop the theft of an attack helicopter by the crime syndicate Janus. MI6 later detects the copter at a Russian radar installation destroyed by a satellite-based weapon: GoldenEye.

Bond goes to Russia to investigate, meets a Russian gangster (Robbie Coltrane), finds an attractive computer programmer who survived the attack at the radar base (Izabella Scorupco), and learns the head of Janus is a surprisingly-lively 006 determined to take revenge on the British government for the betrayal of his parents’ people. Various hijinks occur, including fight scenes with Janus assassin Xenia Onatopp (Famke Janssen). It builds to a climax in a Cuban radar base, but not before Bond drives a tank through Saint Petersburg while impeccably clad in a three-piece suit.

GoldenEye looks different, bright and colorful, and moves at a sharp pace. It has a larger budget than its immediate predecessors, and you see it on screen. The world’s bigger and richer, and there’s a high-tech gloss for the first time since Moonraker in 1979. The web hasn’t yet reached the computers in this film, and a character can ask for a 14.4 modem with a straight face, but there’s an expressionism in the fluorescent sheen of computer-filled rooms that sells a tone and a world, just as Bond films were able to do in the 1960s.

MI6 headquarters has seen a radical upgrade. Not least is its chief: Judi Dench debuts here as M, and is one of the best things in the movie. She and Bond have a different kind of antagonism than the teacher-schoolboy dynamic of previous M’s and Bonds, and one that works with the themes of the movie. She tells Bond he’s a relic of the Cold War; by contrast, she’s looking to the future. You see it in her office, where the oil paintings and dark wooden walls of her predecessors have been exchanged for modern color-coordinated architecture with recessed lighting. Set design conveys the character’s inversion of values, and the updating of the Bond franchise is used to bring out the subtext of the story.

Sean Bean plays what he’s given well and is allowed to take his character surprising places. He challenges Bond as only somebody who knows him can. There’s a subtextual queerness between Bond and Trevelyan: “James and I shared everything,” he brags. “Absolutely everything...”

But it might be most surprising when he tells Bond the truth of his family history to undermine Bond’s faith in Britain. That questioning of Bond’s core values is surprising and even disquieting; Bond movies aren’t supposed to dig so deep. It challenges what we think we’re going to see in these films, acknowledging at least a little of Britain’s dirty imperial history, and if the theme’s not pushed far it may be that there was no way to go any further with it without destroying the basic idea of the series.

The only problem with the movie is that many of the distinctive aspects fade away as the second half goes on. There’s a reversion to formula, if successful formula. 006’s individuality is lost, though his personal connection with Bond keeps the drama building through a satisfying climax.

Bond seducing his psychological assessor near the start is a direct statement: in this film the censor of the audience’s superego will be seduced and subverted by the pleasure principle. GoldenEye succeeds because it does just that. For more than 25 years Bond movies have featured exhilarating sequences; this one’s consistently exhilarating all the way through. Brosnan's movements and delivery exude a confident Bond even as the film pushes the envelope for a Bond movie. It’s not the besy in the Bond canon, but it’s the most thoroughly entertaining.