Italian director Lina Wertmüller's film, Swept Away, is an unusual love story. It starts on a yacht at sea, where the female protagonist, Raffaella (Mariangela Melato), a rich and sexy right-wing blonde regularly taunts leftist deckhand Gennarino (Giancarlo Giannini) for such foibles as his working man's b.o. When she and her girlfriends sunbathe topless on the deck, bug-eyed Gennarino peeps on them, although he mutters to himself in his angrier moments that Raffaella is an "industrial bitch." He's a conflicted man whose libido's not dovetailing with his politics, a plight that Raffaella shares.

Wertmüller is laying the groundwork for a riveting turnaround, as the stinky commie will soon find himself holding all the aces, a switch that's amplified by the sheer repulsiveness of the object of his desire, a shrill harpy who sets the wheels of her own degradation in motion with her poor judgment. Raffaella's about to get payback when the power dynamic reverses, but the director delivers her character's hard lessons with a curveball. In fact, many of the film's numerous detractors would call it a beanball.

Gennarino thinks it's a bad idea to take her out on a dinghy late in the day, but the noisy blonde insists on it. The bearded communist, who strums his guitar after dark while singing a soulful song, initially comes off as the proletarian hero archetype, but his darker side is revealed when the motor malfunctions and the two nemeses end up alone on a deserted island where Raffaella's cash is worthless and Gennarino's survival skills are king. The arrogant princess is no longer in the position to complain about the overcooked spaghetti and warmed-up coffee he served her on the yacht.

Raffaella's motormouth Marie Antoinette act when she had the upper hand provides ample fuel for schadenfreude when she becomes dependent on Gennarino for sustenance, but the director complicates things by giving the audience reasons to sympathize with her. Raffaella's slow in grasping her diminished status once they've arrived on the island, but the viewer knows what's happening when Gennarino responds to her insults by calling her a tramp, a parasite, and a shag bag. The rules have changed. The hungry socialite watches the "Sicilian savage" catch a lobster, start a fire, and cook it, and new awareness enters her eyes. When she calls him a "communist prick" for not sharing his feast, it's with tears in her eyes this time, although she's still not quite willing to submit to her new master.

An empty stomach, however, can change all kinds of attitudes. Soon enough, Raffaella's washing Gennarino's underwear in order to "earn" her meals. She must address him as "Mr. Carunchio," and he doesn't allow her to sleep in the shelter that he's found. Gennarino suggests a sexual bargain to secure her lodgings, but Raffaella rejects him with "ugly Abyssinian!" After she spends a cold night outdoors, he slaps her around when she remains defiant in the morning.

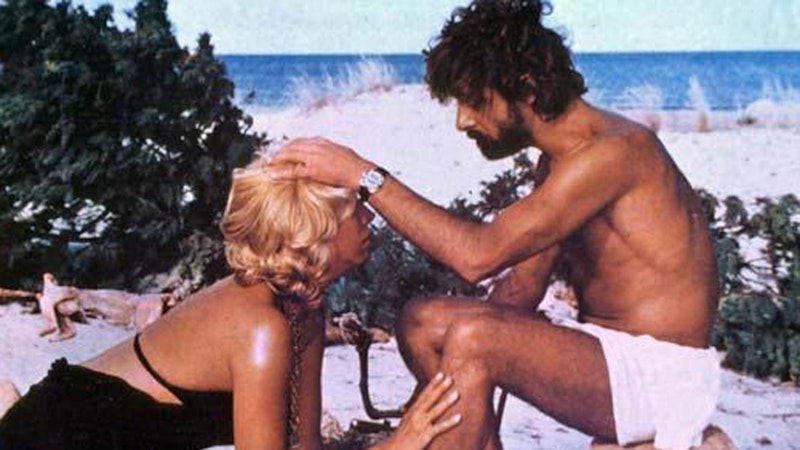

This is the point in the film when those with progressive politics might become uncomfortable, as feminism normally accompanies a devotion to the class struggle. Gennarino morphs from guitar-strumming advocate for the poor into Stanley Kowalski, but a leftist resorting to violence following a sudden rise to power is no shocker. In the pivotal, and most cinematic, scene of the film, he pursues Raffaella as she flees over the sand dunes, continuing to beat her. And then the big moment arrives: Gennarino rips off her bikini top in what looks like is going to be a rape scene, but there's a surprise—he quickly senses her desire for him, and then denies her wish in order to further establish his dominance.

That begins the aristocrat/peasant S&M love story at the heart of the film. Raffaella pursues Gennarino, and their affair begins. The continued slaps to her face are a turn-on for her. The progressive viewer with the post-#MeToo mentality is even more conflicted now, because even though a woman with so much white privilege and "whiteness" (and those "white woman's tears"!) is getting her comeuppance at the hands of a swarthy prole, this woman's enjoying being abused by her male oppressor. Louis C.K. got canceled for a lot less than what Gennarino did. Swept Away would never get released today.

As it turns out, a pampered woman wasn't getting what she wanted from her polished, educated husband. What she discovered she really wanted was an uneducated, rough beast who could put her in her place. That's a tough sell in the 21st century. Lina Wertmüller, one of the most successful Italian directors of the 1970s, was a leftist who lived in a time when that didn't necessarily mean that you were a feminist. She liked pushing people's buttons. Swept Away launched the careers of Giancarlo Giannini and Mariangela Melato. The actress surrenders all emotional control in her convincing performance of unconventional love. Her transformation from a condescending oppressor of the working class to a woman in love tests the boundaries of believability, but she makes it credible. It's not an act she's putting on just to survive on the island. Giannini, famous for his expressive eyes, softens his persona as their affair deepens, and the genuine tenderness he eventually shows towards her adds a layer of depth to a film that could have come up short as a one-dimensional story of class-based revenge.

Wertmüller's not generalizing with these characters—she's just using them to tell a story that moves from humor to eroticism to pathos and, finally, to sadness. It's a shame that the director failed to stick the landing with her film's denouement, which takes place after the couple has returned to civilization. Perhaps, in the end, she found it too hard to get beyond her left-wing politics and deliver a final message that didn't feel heavy-handed. Up until then, however, her skill as a filmmaker is on full display.