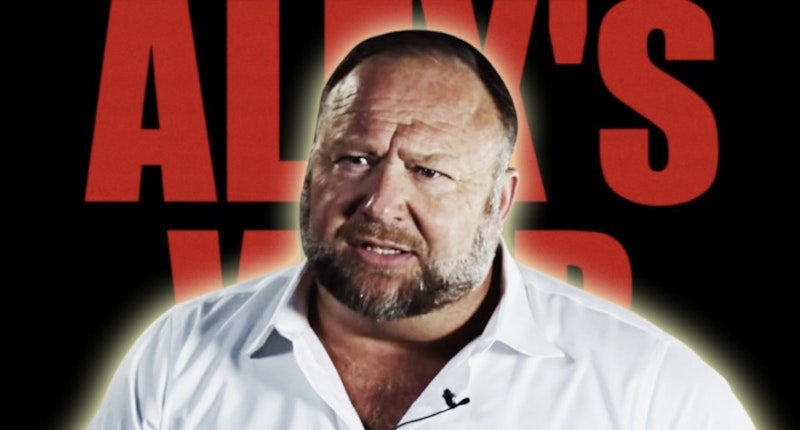

Controversial InfoWars host Alex Jones has to be among the most investigated, profiled, and criticized figures in the recent history of American journalism. Over the course of three decades in the public eye, Jones evolved from a soft-featured, handsome public-access host in Texas whose broadcasts channeled and popularized the work of conspiracy theorists such as Bill Cooper and Gary Allen to a beer barrel-shaped shouter whose presentation style is a sui generis cross between a pro wrestler and a home-shopping host.

That hybrid style suits Jones because, like a wrestler or a television salesperson, he’s trying to talk his audience into parting with their money. Denied nearly every other form of revenue due to platform bans from the likes of YouTube and Facebook as well as somewhat understandable reluctance on the part of advertisers to do business with the show, InfoWars subsists on the proceeds from direct sales of products pitched by Jones. This fact, along with nuggets of information like Jones’ lawyer’s admission during divorce proceedings that the host is merely “playing a character,” would suggest there’s quite a bit beyond the InfoWars kayfabe—as do the host of other labor problems at the independent media organization covered in a recent CNN Special Report.

Director Alex Lee Moyer’s new documentary makes no effort to penetrate that kayfabe. This is by design, as indicated by one of the few pieces of editorial intervention in the entire film—a title card reading that the scenes assembled in the film represent “a constructive effort to promote discussion.” Moyer’s 2020 directorial debut TFW No GF follows a similar line, turning a camera on Frogtwitter “main character” Kantbot as well as four other unfortunates as they discourse and crack wise about life, posting, video games, and noted incels such as UC-Santa Barbara mass shooter Elliot Rodger and Toronto van attack mass-murderer Alek Minassian.

As in TFW No GF, Moyer eschews the excessive contextualization common in many of today’s direct-to-Netflix documentaries, instead turning the camera eye on Jones himself and utilizing old footage broadcast by or about Jones to accompany his own narration of a life that saw him evolve from being a curious child of left-libertarian hippie parents to his present-day position as the world’s leading exponent of conspiracy theories.

The thought that this camera-eye method is somehow less “biased” than excessively contextualized or overly-narrated documentaries isn’t correct. Moyer’s presence is obvious in innumerable small touches, from shots that hang lovingly on Jones’ weird, wide face—which is graced not so much by a double chin as a pair of bulging double wattles—to intimate moments such as an InfoWars employee noting that this is an unusual workplace to a clip from the show that captures the weariness in Jones’ gravelly voice as he bellows about how the FBI’s investigation of his allegedly fake five-star product reviews came to naught.

There are also two moving speeches captured directly by Moyer. The first comes toward the middle of the film and features Jones staring right at the camera, looking exhausted and worn, and remarking that it was all for nothing, that he knows the end is near, and that he hopes to find himself living among the angels in the next life. The second comes at the conclusion of the film, when Jones is outside shooting guns with his son, during which he says that he can feel “eternity” in these small, perfect moments.

This is a long film, with a runtime in excess of two hours. The pacing is deliberate, and there’s certainly something evocative in the way the camera follows the dense, energetic Jones as he hustles hither and yon or waddles out from behind the Georgia Guidestones after micturating on those hated and since-demolished structures. Through it all, you begin to feel as if you're right next to Jones, even if the excessive use of non-diegetic sound in the film’s most emotionally arresting segments can at times seem like it’s dictating the particular vibe of that moment.

That said, there are obvious gaps in a film about a figure this well-documented. Jones isn’t the least bit revealing about his personal life, and no right-wing figures briefly associated with InfoWars—such as Gorilla Mindset author Mike Cernovich or Harvard-educated Obama birther Jerome Corsi—appear to offer their own perspectives about working with him, much less the left-wing and liberal do-gooders who despise him. Instead, you get to see, at least in bits and pieces, a slightly more vulnerable side of Alex Jones, a clever charlatan whose performance artistry has made him the darling of the Red Scare-centric podcast scene the way another Moyer subject, the much-memed Kantbot, once was. Whether this is good or bad is something I leave to readers to decide, much as Alex’s War leaves the final assessment of Jones’ character in the hands of viewers.