The pilot nicknamed “Porco Rosso”—Captain Marco Rossellini, to those who knew him before he became a pig—stands aboard a tugboat headed to Milan, reading a newspaper. The ship’s carrying the ruined remains of his seaplane, shot down during a dogfight. “‘Is Porco Rosso Alive or Dead?’” he reads aloud. “Good question.”

Loosely based on director Hayao Miyazaki’s serialized manga The Age of the Flying Boat, Porco Rosso began as an animated short for Japan Airlines and ended up a movie the director essentially made for himself. The film zeroes in on two of the director's lifelong obsessions—Italy and airplanes—and the result is an adult film about love, longing, pain, and regret starring a womanizing anthropomorphic pig with PTSD. And, perhaps unintentionally, it’s the story of an alcoholic.

In a 1997 interview with Animerica Anime & Manga Monthly, Miyazaki expressed his dissatisfaction with the finished film: “To my mind, animation is for children. Porco Rosso flies in the fact of that assumption. Moreover, as a producer I still think Porco Rosso is too idiosyncratic a film for a toddlers-to-old-folks general audience. That it turned out to be a hit was an unexpected stroke of luck. It's actually kind of disturbing.”

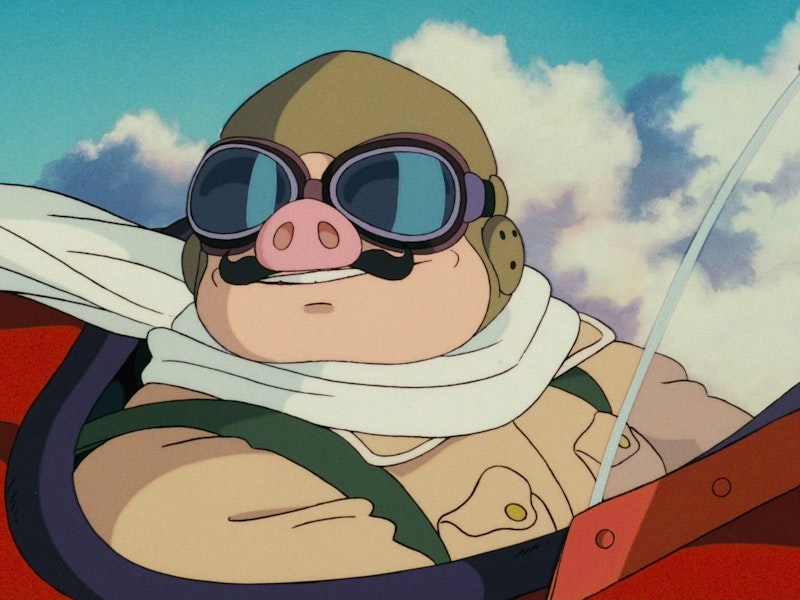

Porco Rosso’s “idiosyncratic” opening moments make it clear that this isn’t a quiet-afternoon-with-the-kids Studio Ghibli feature. When we meet the hero, he’s passed out with a bottle of wine in front of him. He wakes up, annoyed to be disturbed, and takes a call about a job. Porco lives alone on a tiny, nameless island in the Adriatic Sea. Aside from a small tent, his trademark cherry red seaplane is his home.

The life of an alcoholic is lonely. They may have many friends or loved ones but drinkers inevitably get drunk alone, taking refuge in numbing silence. After Porco rescues a group of precocious hostages from a gang of sky pirates, he takes a solitary meal at the Hotel Adriano. Housed in the remains of an ancient estate, the Adriano is a jewel in the darkness of the Mediterranean night and a refuge for pilots.

Inside, Porco exchanges mumbled, half-hearted pleasantries with a few well-wishers (and some unhappy sky pirates) before he heads to a corner of the Adriano to dine alone. Behind him, framed, faded photos of better days hang on the crumbling wall.

Porco’s solitude is interrupted by Gina, the hotel’s glamorous proprietor and one of the few people who knew Porco when he wasn’t a pig. Gina’s nearly as isolated as Porco, and the two loners share a profound bond from childhood. She’s received news that the remains of her husband (the third in a series of pilots killed by war) were finally found. “My tears dried up long ago,” she tells him after a lifetime of loss. Porco, like a brother to Gina’s first husband, can’t find the courage to adequately comfort his lifelong friend in her grief. Instead, he coughs out a self-serving quip. “The good guys always die,” Porco says, raising his glass in a cynical toast.

This scene is important: Porco’s curse isn’t looking like a pig—he’s become a pig. We don’t know how long Marco has been the legendary aerial bounty hunter “Porco Rosso”—but it’s been long enough that no one’s ever surprised by his appearance.

Yet, the Porco we first meet is surly and miserable. He’s a sexist. He takes stupid risks, like when he travels to Milan for a new plane fully aware that the local fascist authorities have a warrant out for his arrest (Porco is implied to have deserted the military of his home country out of moral objection). When Porco’s questioned about his choices, he is quick to dismiss them with a reminder that he’s, “just a pig.”

Mostly, Porco hates himself. His friends and brothers-in-arms died while he lived and that survivor’s guilt has only festered with time. Once, as Marco Rossellini, he fought for his home. As Porco Rosso, he fights for money to fix his plane, enjoy nice meals and sip wine. He’s even blind to Gina’s obvious affection for him, a love that could blossom into something greater if he could only see it.

Unwilling to engage with his humanity, Marco became Porco and a man became an animal. In a rare moment of vulnerability, after telling the story of the near-death experience that left him no longer human, Porco wonders if he even survived when so many others died. “The good ones are the ones who died. Or maybe I'm dead. Life as a pig, it's the same thing as hell.”

Self-loathing is the handiest weapon in the arsenal of an alcoholic in denial. “Surely, if I hate myself more than the people I’ve hurt, let down or otherwise failed, things will be okay. For me, drinking became an almost unconscious ritual most nights, but it was driven by the simple fact that I didn’t like who I was. Look around any bar, at any time, and you’ll see a few of us nursing a whiskey or a beer. We know, on some level, this isn’t good for us and yet there we sit. A sea of pigs drinking on an endless chain of desert islands.”

Porco finds this worldview challenged when Fio, his airplane designer’s 17-year-old granddaughter, interrupts his life of emotional exile. Fio’s a genius airplane engineer and architect in her own right, a challenge to Porco’s personal philosophy of crude sexism. Using her designs, it’s an all-female workforce that builds Porco a new and improved seaplane.

Fio also doesn’t humor the aerial ace’s romanticized self-pity. She sees the best in him, the courage and heroism he claims he shed with his humanity so long ago. In her optimism and bravery, Fio sees him as a man and not the pig he claims to be. At one point, Porco’s dimly-lit face even appears human before her, if only for a moment.

Porco’s curse is the core conflict of the film, but it’s more complex than a fairy tale animal transformation. Other characters don’t even seem to care that he’s a pig: we watch him go about his life in the way that a human being would, with only occasional mentions of his appearance. Women adore him, and he’s seen by the world as a legend; even his enemies begrudgingly respect him.

Most movies of this kind would have ended with Porco’s transformation back into a human. Cathartic magic transformations are central to many of Miyazaki’s other films: Chihiro’s parents in Spirited Away themselves revert from oinking pigs back into humans. Maybe there’d even be a wedding or a shot of a gray-haired Marco and Gina holding hands in the Hotel Adriano’s rooftop garden.

Porco Rosso isn’t that kind of film. The end of Porco Rosso is Miyazaki’s most ambitious and ambiguous: after successfully defeating his American rival Curtis in an aerial duel-turned-bareknuckle boxing-match for Fio’s honor and winning the money needed to pay off the reconstruction of his plane, the two pilots decide to distract dozens of incoming military planes long enough to give their audience enough time to escape to the Hotel Adriano.

In a narrated flash-forward set many years later, Fio speaks fondly of Gina, Curtis, and even the sky pirates she befriended as a teenager. She also tells us that the fight was the last time she ever saw Porco Rosso.

Human beings—real, non-animated ones—don’t change instantly and the beauty of the film’s ending is how open to interpretation Porco’s fate is. His huge moment of self-realization at the end of the movie, that Gina loves him, believes in him and waits for him, is just seconds old when we see him for the last time. Self-realization is not self-actualization, however. How he acts on this information—whether he lives for moments or for decades—is left unknown. Like any of us, he could just as easily fall as soar.

Did his luck finally run out at the hands of Italian fascists? Or did he regain his humanity and give up a dangerous life in the sky for a life on the ground with Gina? Maybe he found another empty island and another bottle of vino to crawl back into.

Is he Porco Rosso or Marco Rossellini? Is he a pig or a man? Dead or alive?

—An expanded version of this essay appears in Drying Out at the Movies: Six Sober Essays by Max Robinson, available early next year.