Surely you weren’t expecting that Michael Mann, who directed the most bloated and pretentious cops-and-robbers saga of all time, Heat, would approach the story of John Dillinger with any degree of subtlety? You must have assumed that this movie would run two and a half hours and feature multiple climax-worthy gunfights, just as it stands to reason that Mann would stack his film with broad-shouldered, pock-marked professional men who commit themselves unwaveringly to the task at hand, pausing only for manly, Wagnerian death sequences. And obviously, you weren’t counting on any degree of complexity for the female characters.

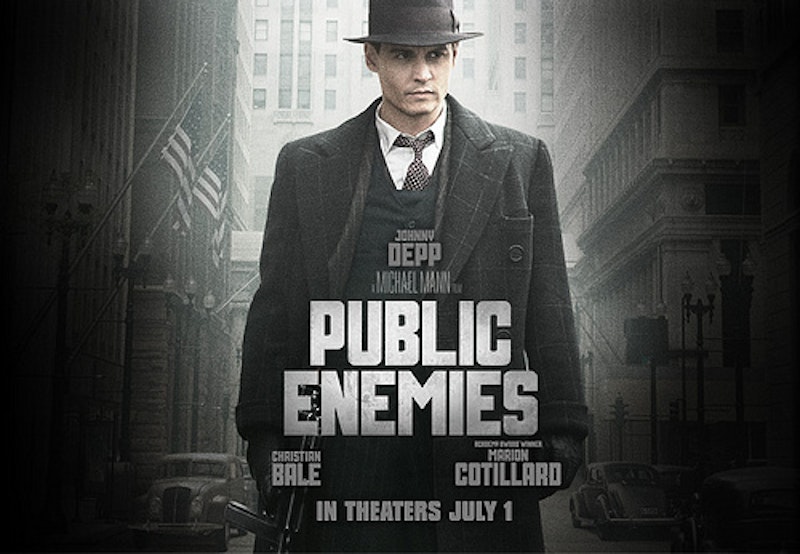

For its opening half-hour or so, Public Enemies seems, like a lot of Mann’s films, poised to astound. You see Johnny Depp and Christian Bale, two enormously famous actors who’ve spent a lot of recent screen time in capes and makeup and such, looking like themselves again, seemingly just ready to act. And Billy Crudup, last seen floating, glowing, and naked in Watchmen, is let loose and allowed to chew scenery as a strutting, obnoxious J. Edgar Hoover. They’re all dressed, like their co-stars, in impeccable three-piece wool suits and heavy pomade, and they ride in gorgeous black-and-chrome vintage cars. This is the visual language of much classic cinema, and Mann seems up to the task; his digital camera captures this pulpy fantasia from up high and up close, in wide-angle outdoor shots and intimate, over-the-shoulder glimpses. Mann creates a sense of scale to match the mythical-historical story, and his athletic depictions of jailbreaks and bank robberies feel exhilarating.

We’re introduced to the characters, shown how each goes about their business, guided through a few dynamite set pieces, and then… that’s it, really. The movie sprints out from the gate and then simply maintains momentum for the next couple hours, without any real insight into Dillinger’s mind or character. The general rhythm of the film, too, never changes; after Dillinger’s love interest, Billie Frechette (Marion Cotillard) is introduced, Public Enemies gets stuck in a gunfight/romance/death loop, and Mann is simply terrible at the latter two. As in Heat and Collateral, people are murdered in creative, exciting ways throughout Public Enemies, but the moment the scenery slows down and he focuses on a person’s actual death, Mann always resorts to schmaltz. We’re shown a number of slow death scenes where one man tries to save his friend or comes to accept his inability to do so, but it’s never clear why we should care; none of these characters mean anything to us. Similarly, it’s clear why Frechette, a poor daughter of a Frenchman and Native American woman would be attracted to Dillinger’s hook—“They only care about where people come from; I care about where they’re going”—but the quickness with which their fling becomes a life-defining romance doesn’t quite add up. Unlike Goodfellas, which was effective precisely because Martin Scorsese allowed the key female character to speak for herself, Public Enemies’ leading woman, despite her historical precedent, functions more or less as a plot device. Of course Dillinger’s got a beautiful gal; that’s what gangsters do.

Goodfellas is also worth bringing up because of its inspired aesthetics. Not every gangster movie needs to be as flush with extravagant tracking shots and a rambunctious period soundtrack, but Public Enemies, even viewed outside the historical precedent of the genre, is a frequently hideous-looking movie. Mann, far from the neon glaze of Heat or the glowing palette of The Insider, now shoots his pictures on video, like most contemporary directors. I don’t know enough about camera models to say what he’s doing wrong, but I do know that Steven Soderbergh, whatever his flaws, managed to make the first part of Che suitably gorgeous despite eschewing film stock. Mann, however, shoots Dillinger & Co. like he’s using a camera phone—swooping at some points, sitting still at others; using only available light but without attempting verite realism in any other aspect of the production. Under different circumstances I’d willing to accept this as a stylistic tic, the way the same nearly pixilated video quality made sense amid Collateral’s contemporary urban nightscape. But Public Enemies’ purposeful drabness seems perverse, e ven lazy. The quality of the image changes from shot to shot, as does the quality of the sound editing.

This bizarre aesthetic mismanagement lowers Public Enemies from the level of mere disappointment to a total boondoggle. Putting aside the basic ugliness of the film, what do Mann and his longtime cinematographer Dante Spinotti mean to say about Dillinger, or American crime, or celebrity, that warrants this not-quite-documentary treatment? Like the various bits of characterization and thematic gestures that go nowhere, the cinematography in Public Enemies is both distracting and poorly handled. The violent scenes are meant to jar us and make us feel as if we’re in the car with America’s first bona fide gangster, but any time someone dies we get the same overbearing, hammer-of-the-gods orchestral accompaniment, and this constant ping-ponging between two extremes is jarring rather than exciting, as the material demands.

Early in their courtship, Frechette tells Dillinger she wants to know more about him, and he responds with a lightning-quick mini-monologue about his upbringing, lifestyle, and dreams. Depp delivers it like a pro, and in the context of the scene it feels like we’re watching an iconic movie moment materialize right in front of us. But the two hours that follow don’t take Dillinger to task for that self-glorifying moment, just as they don’t teach us anything about the man that we don’t learn from that superficial snake oil. And so we’re left with a crime movie that judges no one, an epic that can’t decide whether it’s an opera or a procedural, a character study with no character at the center. We’re left with an ugly mobster muddle.

Public Enemies, directed by Michael Mann. Universal Pictures, 140 min., rated R. Now playing everywhere.