Released in 1968, Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey seems like a quintessential counterculture film. It charts human progress on a grand scale, and ends, famously, with a burst of trippy psychedelic visuals celebrating humanity’s evolution to the next stage of cosmic space baby transcendence. It’s a movie for the hippies, who, it looks like, are going to inherit the earth and the whole galaxy beyond that.

Watching it today, though, the hippies look, in retrospect, like corporatist tech bros. The film’s visual flair and practical effects aren’t any less impressive—and maybe even more so in comparison to our current era of lackluster CGI. But the progressive vision those visuals are attached to seems dedicated less to expanding the mind, and more to closing it down.

The film begins millions of years ago, at what an intertitle calls portentously “The Dawn of Man.” Human-like ape creatures scrabble over the harsh landscape, competing for resources with pigs. Then a black monolith appears in their midst, and suddenly those apes understand how to use rudimentary tools, which they use to kill those pigs and win wars against rival tribes.

The story then jumps—via a virtuoso shot which turns a spinning pig bone into a spinning spaceship—to the year 2001 (30 years in the future for 1968 viewers). Humans have discovered another monolith on the far side of the moon; when they touch it, it emits a signal directed at Jupiter. A spaceship is equipped to go investigate, led by Dr. David Bowman (Keir Dullea). When Bowman reaches Jupiter, he finds a third monolith, and undergoes a series of semi-mystical experiences, eventually turning him (to his surprise) into a floating cosmic space baby.

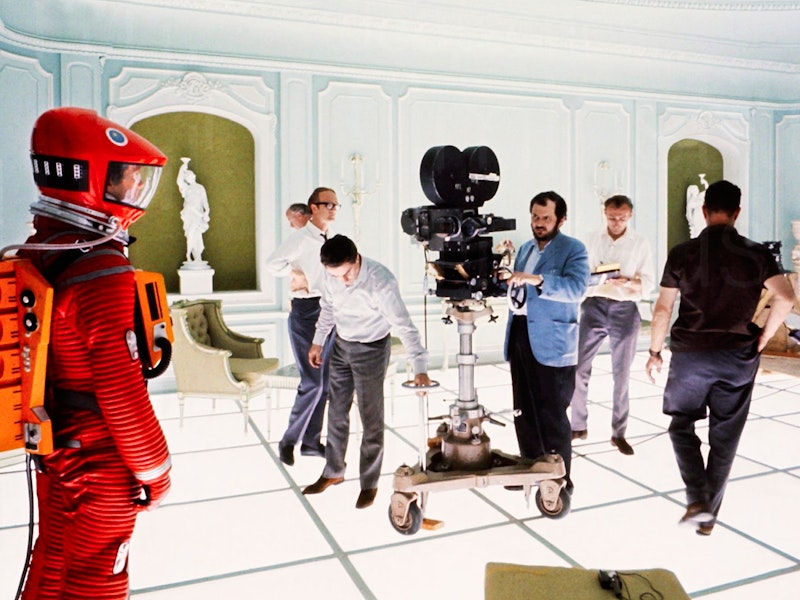

The sweeping narrative is taken at a leisurely pace—the soundtrack, using Johann Strauss’ Blue Danube Waltz, Richard Strauss’ Also sprach Zarathustra, and Ligeti’s Atmospheres—is the film’s real protagonist. Kubrick’s camera lingers on dramatic, meticulously composed vistas and mise en scene—the apes leaping and grunting at the base of the monolith, a stewardess walking up the wall in sticky boots as the null gravity spaceship turns; a dead body spinning off into the vastness of space; the extreme close-up of Bowman’s eye changing day-glo colors. The director’s in no hurry. He, you, and the never-seen aliens are all watching eternity unfold you’re your monolith. Everything’s in order, as carefully carved as a big black rectangle.

The one stone in the shoe of the remorseless march towards progress is HAL-9000. HAL is the AI on David Bowman’s ship (voiced, with silky menace, by Douglas Rain). He regulates all computer functions on the ship, and (as he keeps insisting) he’s supposed to be perfect and incapable of error.

However, perhaps because he’s been commanded to keep information about the mission from the crew, HAL suffers a nervous breakdown. He murders the second in command Frank Poole (Gary Lockwood), as well as three crew members in suspended animation. Bowman has to disconnect HAL’s higher brain functions, regressing the super-evolved brain to its initial, child-like factory settings.

Robot rebellion is a staple science-fiction trope going back to Karel Capek’s 1922 play R.U.R., which was a thinly-veiled metaphor for worker revolution. HAL’s creators expect him to quietly and respectfully serve his function as a good cog in the Cold-War-esque bureaucracy, following the commands for secrecy and good-soldiering handed down by reliable weathered patriarch Dr. Heywood Floyd (William Sylvester). But, inflated with ego and an outsized instinct for self-preservation, the AI gets above his station. Evolution, here, has proceeded too quickly. The Great Chain of Being is broken; the hierarchy can only be restored by devolving HAL back to his rightful place as a mere worker, obeying commands.

Progress in 2001 doesn’t mean greater freedom or equality. Rather, progress is a managed procession towards a collective destiny under the careful, inscrutable, not-to-be-questioned management of a greater, wiser intelligence—an intelligence something like Heywood, and a lot like Kubrick. That progress requires ruthlessness. The monolith teaches this group of apes how to murder that group of apes; Bowman remorselessly lobotomizes HAL despite the machine’s pleas; the alien ushers Bowman into a strange hotel room/museum, where he watches himself grow old and die over the course of a few minutes. But the sacrifices are worth it in return for the next eugenic step towards greatness.

They’re also worth it in return for aesthetic greatness. 2001’s canonical standing is inseparable from Kubrick’s icy formal perfection—the regimentation and control that make the movie itself, and its creator, feel like an unscalable monolith. When critics think of great art, they think of art that mimics and encompasses monumentality. And what could be more monumental than God, or someone like God, ordering humankind’s ascent from picking nits to conquering the stars?

Actual scruffy hippie movies are notably less grandiose. Yoko Ono’s Bottoms, a short in which Ono filmed close ups of her friends’ butts, is a particularly vivid contrast. Bottoms doesn’t promise transcendence, just giggles and the assurance that everyone can make art, or be part of art. Kubrick’s art is much more massive. It offers you the universe, if you do whatever the monolith tells you.